This is Monday Meeting Podcast, an episode titled 'A Journey Into Design Fiction' where I introduce the concept of Design Fiction to an adjacent creative community of motion graphics professionals. We talk and Q&A about how visual creativity is used to in the practice of futures design and Design Fiction, and the possibilities implications of Design Fiction for current creative practices. I also touch upon the integration of visual storytelling, the interface between technology and design, and the utilization of imagination in speculative design to propose and question future scenarios.

I had the great pleasure of joining Monday Meeting’s, you know — Monday Meeting as a special guest.

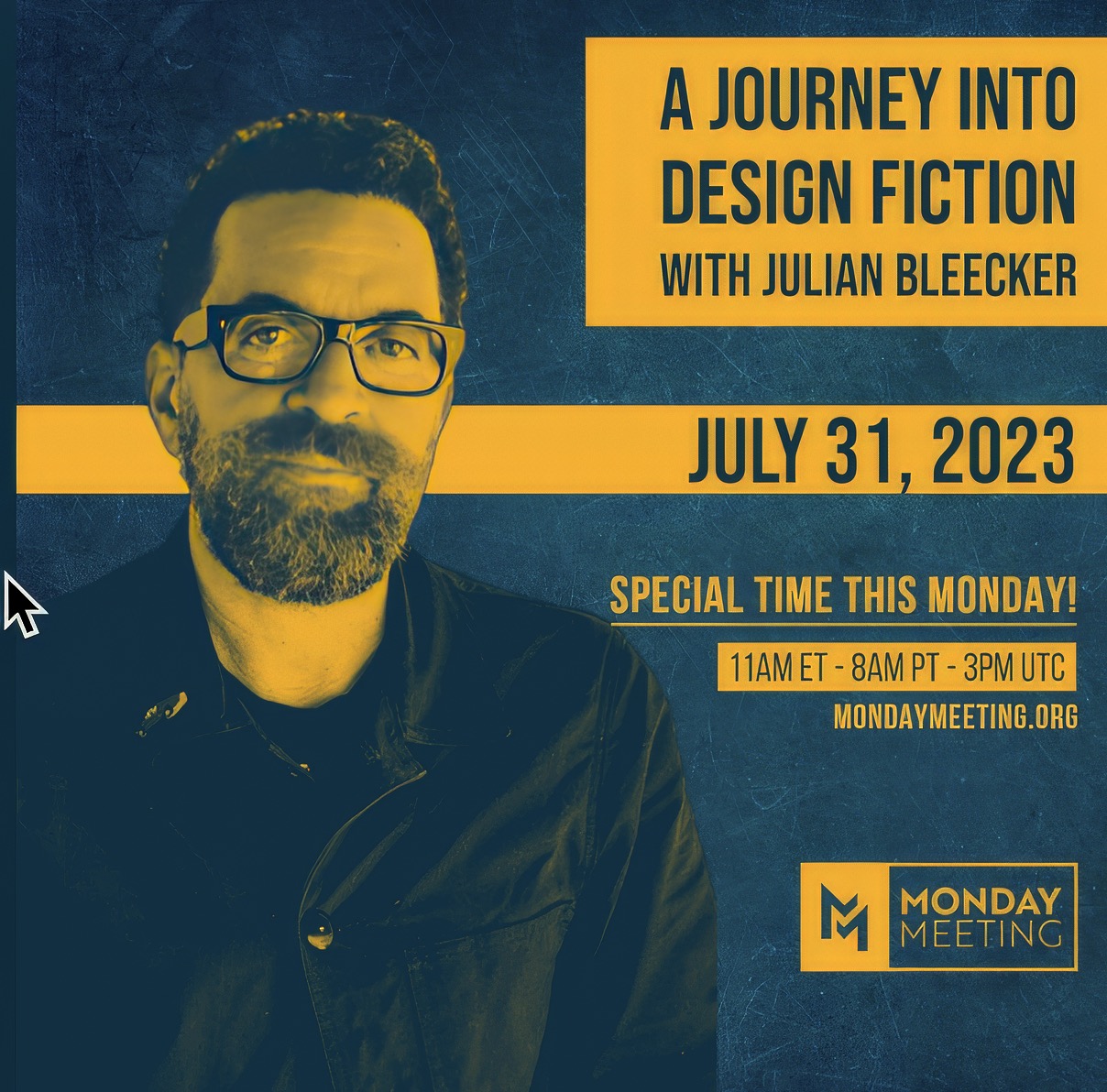

Mark Cernosia: Welcome to this week’s Monday meeting. Today is July 31st, 2023. Monday meetings are a chance for motion designers from around the globe to connect, ask questions, share inspiration, and engage with industry leading artists on a level playing field. My name is Mark Cernozia and I’m here today with Sam Jay, who will also be the co host today.

And today we’ll be having a discussion with Julian Bleecker, co founder of the near future laboratory, amongst other things. Uh, if you have a question, please use the raise your hand button in zoom to be called on. If you’re unable to ask. Your question, because you don’t have a mic or something, uh, just type question in the chat and we will ask them for you.

As usual, this call will be recorded. And if you have any concerns about something that was said on the call, let us know, and we will chop it out of the recording. Um, a few quick opening topics, uh, camp Mograph. We’re. 45 days away from camp, which is awesome. Can’t wait for this to, uh, all go down this year.

Um, but as always a big up to the sponsors that help support this. Uh, we have Otoi, Maxon, Spilt, and Grayscale Gorilla. So thank you so much for your support this year and over the years that we have been doing camp, but without further ado I’m gonna throw it over to Sam to do a little intro and, uh, and get Julian in here for this week’s meeting.

So welcome Sam. Welcome Julian. Thanks for taking time out of your day today to be

Julian Bleecker: on. Totally, totally down for this. Yeah, thanks

Sam J: for having me as co host. Good to see you all again this week, uh, been really enjoying these last several weeks, and I mentioned Julian Bleecker, Bleecker, sorry, a few weeks ago, uh, during a conversation we had that just kind of sparked, um, the topic of design fiction, and so I thought it’d be a great person to have on and kind of spark a new conversation for all of us, thinking about how design in the future can impact us today, And so Julian’s created this very kind of cool thought experiment place for for artists to be able to imagine what design elements look like in the future on things as mundane as a box of cereal and then kind of bring back that imaginative experiment back to our everyday design work and implement those ideas so we can kind of envision ourselves as designers of the future.

But I’ll let Julian talk more about it and, and in his words. And introduce himself to

Julian Bleecker: the group. That’s my cue. Is it? Yeah.

Awesome. Uh, thanks for that. Thanks for that, Sam. Yeah. Um, so I think, you know, I’m going to, I’m going to, I’m going to go out on a limb and say very many of us here in this kind of community who are motivated to work quite visually and to imagine. Essentially, you can look at it as imagine in a in a visual visual way, like, uh, highly creative visual thinkers.

So expressing ideas and visual form. Um, and then, you know, we can take it to different levels. If we were all around pre. You know, computer, we would probably be in that category of, of, uh, you know, similarly struggling artists from another world to the struggling, um, because we have this desire to kind of represent, translate these kind of feelings and visions and dreams that we have into individual form.

And then, you know, in a commercial context, we end up developing that skill and being able to, you know, being quite competent at doing that, helping other people. Called clients translate their ideas into visual form and using all our, you know, kind of skills and all the, all the tools that we all kind of fall in love with because when we see the things that the tools can do are, you know, our reaction inside is like, Whoa, cool.

Right. It’s like, Whoa, that’s cool. How can I do that? You look at all, like just thinking about my own experience with, with 3d tools. Um, Oftentimes it’s like, I am motivated by that. I look at something and be like someone, you know, I don’t know. It could be anything. A beautiful smoke effect. Oh my God.

Houdini. Do I need to learn that now? Uh, Oh no, it’s the new cinema 40. Okay, cool. Let me listen to this, you know, hour and 40 minute tutorial. And just. That’s, you know, that’s, that’s good. That’s good television, you know, just to watch how it’s done. You want to do it. You want to bring your own sort of sense and flavor to it.

And, uh, and, and become competent in it because there’s a sense that. I’ll be able to translate some of these ideas I have in my head into visual form and share them out. And then, you know, you get a kind of something back from that because you share it and then your friends are kind of like, well, that’s cool.

You post it up. People are like, well, man, that’s amazing. And, you know, you kind of, it kind of keeps you moving in this way. And I think, I think what happened, you know, my, my story. sort of starts there. And, and I’m not gonna, I’m not going to do, I’m not going to do the whole history, but I feel I’ve realized now that I’ve been doing this kind of work for, for ages that this kind of work, you’re not sure what that is, but we’ll get into it.

Is that when I was a kid, like I saw stuff and I was like, whoa, that’s cool. And for me, when I was a kid, it was, um, I was really into, you know, sci fi, generally speaking, mostly visual. So, you know, all the, the, the movies and stuff, a lot of it was, um, you know, early days, like when, when all the visual effects were practical effects.

Uh, and then you could see some things like, well, you know, it was, it was practical, but it was a special effect because it wasn’t something that you could do just solely, um, uh, you know, in camera, there’d be like Matt work that was being done. I was like a big fan before I knew who it was of Ray Harryhausen.

You know, his kind of visual special effects work. And there was, uh, it, you know, it was, it was always trying to find a way, uh, to me to enjoy seeing it. But then more than that, just my motivation was like, how did you do that? Because I wanted to tap into that, you know, in a way I wanted to, it wasn’t just, uh, it was something where whatever, whatever my sensibility was as a little kid, like to actually make the thing.

And, um, my, my brother’s, uh, in town visiting and, uh, he’s a, he’s a filmer, uh, DP. And we, you know, just kind of sitting around just musing about like, yeah, when we were, we were kids, we would take my dad’s old super eight film camera and get all the kids in the neighborhood. So we’re making a movie. Um, and we would try to figure out the way to do it.

You know, it was goofy stuff, but it’s like, okay, stand there, roll for a few moments. Okay. Now move out of the way. Don’t no one move just, and then just do another shot. It’s like, wow, he made him disappear. And that was all you needed to kind of create that. Whoa, cool feeling, especially because there was that, there was that gap between like, okay, now you got to finish up the cartridge of film.

And then, Hey, we’re finished with the film. Can we take it to the photo mat or whatever the guy was back in the day, thrift drugs, drop it off. You got to wait a week and a half, 10 days, 15 days, maybe wait for them to call you or you’d go there and check every day after school. Is it in yet? Is it in yet?

Is it in yet? You get the real, and then it’d be like family film night, set up the projector and that kind of stuff. And that was all part of it. That was all part of kind of creating and tapping into that. Whoa, that’s cool feeling. You imagine something. Uh, you know, uh, you know, a little, a bunch of eight or nine year olds running around trying to come up with a, with a plot for a film that involves people disappearing and, you know, uh, whatever, explosions and stuff shot close up of a little firecracker or something.

You were just trying to create a story of something that you imagined in your head. And I think that, that was, that was a, that was a kind of formative set of, Feelings and experiences and, and, and, and all that kind of stuff. And I knew that, uh, there were aspects of, of all those things that I wanted to, that I wanted to tap into.

And, and I didn’t know, you know, I didn’t have, you don’t, you never have a clear head about it when you’re, when you’re a kid, unless you’ve been around a whole bunch of times, you’d be like, this is going to be my life. I’m going to be doing something that translates, you know, some kind of dream or image or, or, or something into a material form so that I can share that with people.

And I ended up becoming an engineer. And I think, you know, looking back, that was a part of that as well. Um, you know, in the terms of, in terms of like translating an idea or a component or aspect of a, of a possible, let’s just call it a possible world that includes, you know, some little. Device of some description, translate that into material form because I think it’s cool.

Um, and then of course you laminate all these other things like does it make good business sense and all the, all those kinds of things. But at the fundamental aspect of like, this is, I like the world in which this thing could exist. Hmm. There’s something

Mark Cernosia: about it. Trying to figure out the

Julian Bleecker: magic trick.

Yeah, exactly.

Sam J: Yeah, exactly. I love the idea of having an effect, like watching somebody disappear and then writing a story around that. You know, it’s like, oh, here’s this cool new tool that Maxon gave us. What, you know, what could I possibly make from that tool? Versus the, the kind of opposite nature of like, here’s a really great story.

What tools do we need to tell it? And that dichotomy. So it’s like, you know, something that’s really story driven. Um, trying to think of a good recent example versus the opposite of that, like the, the new flash movie. Where it’s like, they took a bunch of special effects, and then literally wrote a story around those special effects.

Like, there’s an actual scene where you can tell the thought process of the people who were writing in that boardroom around the table, where they were like, Oh, this would be really cool. Now, where’s the story that wraps around it? And just ridiculous scenes that make no sense, but they wanted to show that

Julian Bleecker: effect.

Yeah. Yeah, you kind of, you kind of never want to do that if you want to be a good storyteller, but you know, but it’s interesting. Yeah, because there there are there you could you could chart these moments. Um, and I actually did doing for part of a, um, when I was, when I was getting, when I was in school, just kind of charting these, these moments in the, uh, the sort of modern digital.

Special effects kind of era where a, uh, where the, we’re essentially like the, you know, the algorithm or the technology, you know, the, the, the thing that you get the computer to do, um, became, became, you know, became over, you over indexed on it. Right. So, so the, um, the. I think it was in a Michael Jackson video.

Was it? Yeah, it was the, um, I’m looking at the man in the mirror, whatever the song is. I was just at Quincy Jones’s birthday party at the Hollywood Bowl. He didn’t invite me. It was just a big concert at Hollywood Bowl. And so they went through the whole, his whole cannon. It was amazing. And I remember when I was listening to that song, I was like, Oh yeah, that’s when they had the effect where they had, they did the morph between different, um, you know, just different kinds of people.

So you get this. Oh yeah.

Mark Cernosia: Black and black or white or whatever

Julian Bleecker: it is. Black or white, that was the one, yeah. And so, and so, that was amazing. You know, there’s a story there, so it kind of makes sense. But also, there’s that sense of like, Oh my gosh, how’d they do that? You know, it looks beautiful, like, you know, beautiful and seamless, you know, to the degree that seamless was something back then.

It was amazing. And then, um, Uh, for a long time, I was a, as a subscriber to, um, Cinefix, the magazine, um, and, and then, you know, they’ve kind of, they kind of break it down. Like this is, this is the effect and these are the people who graded and they celebrate the, the creative, um, folks who kind of, uh, established that effect.

And then you see it like in gasoline commercials, the tiger turns into the car and it’s kind of like, is that necessary? I get what you’re doing. You’re telling the story. We’ll put a tiger in your tank. You know, and so it’s like, well, how can we do that? Like, what does that mean? What’s the visual, what’s the visual metaphor for that?

Well, there’s this effect that those guys over, you know, in Burbank are doing. We could talk to them. They could probably morph a tiger into a, into a Mustang or something. And that’s what they did. Um, And the same thing with like a whole bunch of other, other, you know, I guess kinds of effects or, you know, like a, like an archetype of an effect.

Yeah.

Sam J: Uh, so Julian, when, when you and I started talking, we, uh, you told me about how you met, um, I forgot his name, your kind of partner in design fiction, uh, and how you guys, I, I think I remember you guys like sitting on a park bench or something along those lines. And just starting to imagine this world of the future and what types of design elements Would get used and how that would change from what we’re experiencing now And you and I just started kind of rattling off Other ideas of these these objects that we would we would find in a kind of hypothetical future scenario and I think that this group uh would be a very kind of fertile ground to be able to plant that seed of what would this Very familiar designed object that we interact with every day.

Now, what would that feel like and exist like in the future? And, um, so maybe kind of introduce that. To the group and see what people can possibly come up with on the spot. I have a couple of examples that I can share as well, but. Uh, why don’t you kind of introduce that, that subject

Julian Bleecker: matter? Yeah, so, so, um, you know, 10 or 11 years ago, um, when I was teaching in the film school at USC, um, I met, uh, the sort of remarkable, um, polymath science fiction writer, Bruce Sterling, because he happened to be in Los Angeles.

And, uh, so Bruce and I became, became friends and, you know, we just sort of talk and, uh, muse about, What he was doing, which was he was, he was, uh, in residence at art center, college of design. And I remember I asked him, I was like, what are you doing? Why, why are you doing that? And he’s like, well, I’m, I want to learn, I want to learn what design is like how to design.

And, um, and I thought that was fascinating. Cause he’s like a. Well established science fiction author and that he’s just sort of saying like since I’m going back to school and I want to I want to understand what it is to design. I want to understand about design and, um, and, and so I started wondering what would it be like if you have a science fiction writer who does design?

What would a science fiction writer who does, you know, learns design, let’s just say industrial design, product designs, generally speaking, what would they, how would they tell, could they tell stories about the world in a similar way, but rather than using prose? Rather than using words, it was objects. And I just, I found that fascinating.

And uh, I was, I was stuck in Helsinki during, during, during one weekend, um, in the winter. It was very cold and very snowy. And I just, I just stayed inside and, and just, and wrote an essay about it and what I was thinking around that, that, and I called the essay, a short essay on design, science, fact, and fiction.

Um, and it was just my kind of reflecting on what that practice would be. And I, at the time I was working at Nokia. And I thought it would have some practical value in the sense of like, you know, a company that actually makes products can, rather than doing a purely business analysis of what products should be done or that kind of thing, could you actually create the world in which these products might exist in the form of objects?

Not in the form of like a narrative. Oftentimes science fiction writers, on occasion, will get called in, um, to help sort of fashion the world into which one might be, you know, the future world and what the kind of products might be there and how, and the social aspect of the world. What are people doing and why are they doing it and all that kind of stuff.

Um, and, and that’s super fascinating work. And also, I wondered, could you tell those stories? Um, through, through representations of, of the, of the products. So rather than like a kind of top down narrative, um, uh, once upon a time kind of style, if you just kind of had the things that as if you went to that world, like as if you got into a time machine.

Right? You went to some other world, don’t say the date or time or whatever. This is another world that I’m sort of imagining or dreaming about. And you popped out there, but you, what you’re doing is you’re acting sort of like, like an archeologist, but instead of digging into the past, you’re kind of quote unquote, digging into the future.

So you pop out into this world and you can’t, you know, part of the thought experiment is like, you can’t have a conversation with someone who’s going to tell you everything about the world. You’re almost like, as if the world were abandoned of people, or as if you’re in some kind of state where you can’t actually engage people, talk to them, ask them questions about it.

You can just pick up artifacts. So you grab a newspaper, you grab maybe a magazine that you see at a magazine stand, you, uh, you grab something off the counter of someone’s kitchen. You know, maybe it’s a box of cereal, maybe it’s like some kind of, uh, something that looks like a blender like or food preparation type contraption, and then you bring them back to the present.

And almost like a forensic, um, anthropologist, archaeologist, or, or a forensic detective, you try to make sense of what you saw. So you do the sense making thing of, you know, what are these things? And, and rather than trying to impose upon the world, in other words, rather than by imposing, I mean, being didactic about it and saying, this is what’s going on in the world.

And I, you know, this is absolutely how things are set up. And you just sort of almost open up to, to wondering about the world and design fiction is essentially that process, uh, starting with the artifacts that you bring back. So for example. You mentioned the box of cereal. You might bring back a box of cereal, right?

And what we do as kind of visual designers, uh, is actually create that box of cereal. So we don’t just say, hey, we brought back a box of cereal, uh, that is suggestive of, of the world in which, uh, insect protein is the primary source. of, you know, protein for humans. We actually, we create that box. So we literally do the package design for it, right?

So you got to think of all the elements. And so you might take in a practical sense, you might take like a box of cereal that you just have in your cupboard and look at it and really observe and notice how this thing is represented in the world. What is it about it that You know, it makes it stand out and makes and describes to you some aspects of what this world looks like.

So you go, you dig all the way down. So it’s like, it’s, it’s the way in which, uh, even, even the way in which the contents is measured, maybe it’s not measured by weight anymore. Maybe, maybe it’s measured by like number of grams of protein. Available in this box because what is that signal? You know, if you might say today, I don’t think people would really be into that today.

They want to know how much it weighs well in this other world. People are more concerned with conserving packaging space. So they want to know how densely packaged is this material. Right. Maybe it’s a world. I’m just thinking off the cuff. Maybe it’s a, it’s a world in which, you know, if you, right now it’s like the packaging design, potentially quite wasteful.

I don’t know for sure, but let’s say it might be because you go into your store, you go into your supermarket and everyone is trying to take up much as much visual space as they can so that people’s eyes are drawn to a particular product. There’s another one. So the cereal boxes have gotten broader. As opposed to thicker, right?

So, you know, someday there’s just going to be long, tall little billets of cardboard, uh, you know, with just like one slate of material in it that you got to break off a piece and mix it in the bowl to kind of get it to break out. I don’t know, I’m making stuff up. But these are the things that you experiment with because you’re trying to imply certain aspects of the world that are That have, that have changed and there are a couple of ways in which or in reasons why you might do that.

So one is for us is just kind of visual creators. We might do it because it’s like, I don’t know, this is cool. Like I’m, I’m telling a story about a world and I’m trying to get it to the point where visually someone looks at it. And they start wondering, Whoa, that’s kind of cool. Like, wait, so tell me and you, they open up and they start asking questions and those questions are the key point of it.

Uh, so we’re doing this. Why do we do this? We’re doing this because we want people to imagine the world. Otherwise we want people to imagine that we can live in a possible world, possible, possible near future where things are a little bit. Better than they are today, right? That’s, that’s the kind of, you know, at the, at the base of it, the value or ethical reason why, why you do these things is also a reason why parenthetically, it’s like, I’m, I, you know, I love, I love, you know, really, really well done kind of dystopian science fiction, but also I’m like, that’s not helping.

That’s really not helping because you’re imposing this kind of imaginary of a future world that is, you know, shell shocked and, and, uh, and carbon scored and all those kinds of things. I get all that stuff. Believe me, I love it. You know, like I did trying to create that aesthetic, but if you stop and think, it’s like, well, why am I doing that?

Why am I creating that particular aesthetic? And it’s, it’s because there’s a, there’s a resonance to it. Cause we’ve all. since day zero, we’ve been born into a world in which that’s the, that’s the aesthetic of science fiction, cyberpunk or post cyberpunk or whatever it is. And it’s also like, what about solar punk?

Like suppose we started showing more representations of worlds that seemed more habitable, as fantastical as they may be. I mean, they’re no less fantastical than, you know, Elysium, the film Elysium, like, uh, really? Uh, okay. I get it. I get the story you’re trying to create. But is that the world that we want our, you know, our, our, the generations that are coming up now to really have imposed upon them and to, to the point where they can’t think of, you can’t even imagine another world beyond that.

And so that’s the kind of value ethical reason, you know, why we would want to do this. The other reason is it’s cool to build worlds. From the, from the, from the ground up by ground up. I mean, from the tin of food, can you, can you tell a story about an entire world without using a single bit of pros, except for what you see in the packaging on something that you might find in a corner bodega, what can you tell the whole story of that world in the same way that, you know, Matt, you know, the police procedural where the detective walks in and it’s like, right.

There are two shell casings. There’s a drag mark. There’s no body, but it looks like something got dragged that way. And then the, then the drag mark stops and, uh, look, the clock, the clock got hit by a bullet fragment and it stopped at 6. 04 AM. Okay, cool. Check. You know, that scene where the guy is like Columbo sees everything in the world, just from the evidence around him without having any conversations until he gets to the one guy.

And he’s kind of like, uh, one more thing. One more thing I want to talk to you about. So, and so that, that’s, that’s the beautiful challenge of it. And

Mark Cernosia: one thing that I often find interesting is that like a lot of the, um, visual that we associate with that kind of futuristic design or whatnot might be like the crazy like cyberpunk or like the heads up display type thing and you know,

Julian Bleecker: all that.

And the, the, the, the CRT that makes a noise, purr, purr,

Mark Cernosia: But we have, we have that mixed with like host of apocalyptic like dune type scenarios or like, it’s an interesting thing that you bring up of how no one’s really seems to design something that could actually be habitable. I don’t know if that’s just because it’s just too much to think about. It’s too hard to represent visually or something.

And maybe the Apocalyptic stuff is a little easier because it’s been done before and, you know, the, the map is there, if you will. But it’s interesting to hear you say that because we have had conversations about this in the past and how like, um, you know, some people we know work on these Marvel movies and all these big blockbusters thinking about these systems of how they actually might work.

And then. You know, 10, 15 years later, you see that now in a car, right? And so how some of the, some of the thinking that we’re doing and some of the people in our industry are doing try to represent what the future might look like. I think there’s just not as many applications of that because it’s harder.

Julian Bleecker: Maybe I don’t know. No, it is. It is. It is harder. It is hard. Absolutely. So. So, uh, you know, it’s like rudimentary art history, right? There was a time between, uh, before perspective. Isn’t that crazy to think about? Right. Like, there’s a time when it’s like, and you can see those moments. It wasn’t just all of a sudden.

See those moments where people are still struggling with it. Ah, and you get these, you get these, you know, beautiful paintings that are beautiful almost because they show the struggle of the human mind trying to get a lock on how to represent the world. Right. It didn’t exist. It just, it just didn’t exist.

And it took a lot of hard work to imagine a world that could be represented that way, you know? And it took, you know, whatever the diagrams and we sort of, I don’t think we think enough about the fact that there was a world before that in an art historical context, I’m sure they do. I’m sure it’s like a major topic, but just generally as like visual creators, not saying that we don’t know our art history, but we take for granted that.

Yeah, they were stupid back then. They just didn’t know how to do it. And if you also think it was just another another way, another way of making, so we, we, we developed these new ways of making sense. Sense making is one of the primary things that we do as humans. We got this wonderful, highly vascularized piece of like weird meat in our heads that is able to like do this translation of, of, you know, of feeling into material form.

And it takes, it takes You know, it takes someone, uh, you know, a kind of consciousness that’s willing to go out on a, on a crazy limb to say, I’m going to draw the world this way. And there’s probably all kinds of conflict going on internally and externally. Internally is probably someone doing like, uh, I don’t think you should do this.

This seems crazy. They’re going to think you’re off the hook. It doesn’t even look right. You’re not going to, you’re never going to sell your painting. If you can’t sell your

Mark Cernosia: painting. Like, I mean, 40 years ago, we would never have thought we would have had like. All the information we could ever need, it’s sitting in our pocket.

And it just, it just wasn’t, it just wasn’t even possible.

Sam J: Except that Star Trek was showing that future to us.

Julian Bleecker: Right. And that’s, that’s, that’s, that’s that beautiful feedback loop. There’s, there was, I’m trying to find a diagram that in that first essay I drew, which it’s a super simple diagram. Um, and it was part of, it was part of trying to find the way to operational.

Oh, here it is. It’s not probably not going to work. Yeah,

Sam J: it’s a little, a little blown out, but we

Mark Cernosia: can try to find it online.

Julian Bleecker: Oh, okay. Yeah. So in this, so in this book, uh, I was, it was just a simple diagram that showed the feedback loop from, um, science, science fiction to science fact and it, but it’s a loop.

So there’s no, there’s no, it’s not, there’s no primary, like every, all the ideas come from science fiction. Science fiction is a stand in for the imagination. That’s where those ideas come from. And the expansive imagination that’s able to push through the hurt that you’re describing, it’s harder. The expansive imagination that’s be able to push through is like, I’m going to do this no matter what.

And they’re going to call me crazy. And that’s going to cause a lot of conflict for me. And I’m going to struggle with that, but I can’t help myself. I got to figure out the way to kind of represent this world in this other, in this other fashion. And so when you describe that, the, that, that a lot of it, you know, a lot of the visual, uh, design for, you know, just science fiction film is.

dystopian. Uh, yeah, I mean, we’re born into that. So that becomes the aesthetic that we think, you know, is the only possible one. I’m not saying that we, you know, always necessarily think that, but definitely the people who are going to give you some, that are going to pay you are like, no, no, no, no, these be more carbon scoring.

And how come the, the alien doesn’t look as ferocious as it should. And there’s, you know, they’re good storyteller reasons of that, but it takes, it’s going to take someone at the Vanguard to try something different. It’s going to take someone at the vanguard of this who either who has the, the, the wherewithal, the will, the determination, the grit, and oftentimes, you know, just the kind of like, I don’t care.

I’m going to do this. Right. It means they might have money to say, I’m going to show the world this other way. And we know that there are plenty of visual artists who are doing that, but it’s hard to do because people are going to, a lot of people are going to look at it and be like, I don’t get what you’re doing because I don’t have the visual kind of reading apparatus to do that.

I’m expecting when you say science fiction, man, there better be lots of carbon scoring and there better be. You know, um, scenes in, in dark passageways where, where something’s going to jump out and scare me, um, and all those kinds of things. And, and so, so we see that enough, right. As, as consumers of visual culture, we see that enough that we just take it for granted.

And when someone wants to do something, even, even like the solar punk movement. You know, if someone wants to do that, it becomes, it’s hard to do. Like if you’re going to go to a client, you’re going to say, Hey, I’m going to pitch you this idea. Um, and it’s going to be this, you know, this, this other visual aesthetic, they might be like, uh, I don’t know if that’s going to really resonate with our audience.

We want to draw eyeballs and all that kind of stuff. That, that’s where, that’s where the challenges, but I think for us as, you know, particularly independent visual creators, if we can kind of more collectively start showing other representations upon visually other representations of world, then people start imagining into it and they’d be like, Oh, cool.

What is that? And they see it enough. They’re like, I think I like, actually, I like this better than the blown out cyberpunk. Uh, cause, cause the glass cyberpunk thing, you know, it never made me, never gave me good dreams at night. It never made me think of like. Oh, that’s actually the world we should be working at.

And then I think what happens in that, in that loop from the visual imaginary, the things that we create and the things that get represented in, in films and the stories that begin to tap into that, uh, then those become part of our dreams. And those dreams translate into the next day someone’s going to wake up and be like, I think we should be working more in this direction, whatever it might be.

I’m not just talking about visual design, but even the stuff like, um, when I was at, when I was at Nokia, the studio that I happen to be at here in Los Angeles. was for a period, you know, uh, people rang up from Hollywood so that the Nokia phone from the matrix, you know, the banana thing. So that was, that was designed at that studio.

I had nothing to do with those before my time, but they did all the model making for it, all the model making for, uh, for the, for the, uh, they were actually branded Nokia in minority report, right? So all those things start happening and people see it because it’s a prop in a film. And it integrates into people’s consciousness.

That way you can still go on eBay and get, I think someone, whoever bought the IP for Nokia, uh, after my time, uh, they started making those phones again. Yeah. Like the, the, the banana where you can go on whatever eBay or Alibaba or whatever, and get the phone and it’s good. Functioning feature phone that does that thing.

So, so, and that’s, what is that 20 years later? I don’t know, maybe more than that from minority. Yeah. Right.

Mark Cernosia: Right. Well, and you know, that’s, I see Sarah has a question. I want to pull her in here as well. But the one thing that I’m kind of thinking about through this discussion is like, um, Specifically Apple in their like new headset and everyone’s like, Oh my God, like that thing is ugly.

Well, I, someone’s going to spend 3, 500 on this thing, wear ski goggles around the house, whatever. But in my head, it’s a giant leap forward because what it’s going to start doing is normalizing quote unquote. These kind of AR experiences and how we can start using technology for more things. I think a lot of, a lot of, um, say like gamification of things like we, it’s just so like, uh, part of.

our lives now from, you know, counting your steps or counting calories or whatever that now it’s just like part of our everyday type life, right? Um, and so it’s just interesting to pay attention to some of these things that seem so far out of reach or like that thing’s so whack, you know, like who’s going to wear that?

And it’s like, Okay, but that’s like gen one in a way, or like at this point, who knows what generation that is, but it’s just, it, it’s a giant leap forward. And I also find myself feeling the same way about when the iPhone came out, it was just a new way to reimagine a phone and data. You know, and how that could interface together and all that.

So I just think it’s a really interesting space, but I want to grab Sarah and invite her in to ask her question.

Julian Bleecker: Yeah, no, this is a really fun conversation. And I have a comment and I have a question that goes way back. To when you were just talking about, um, putting together your design process. But first, like my comment on my favorite thing that this conversation is reminding me of is the, there’s, there’s an old design question on like, um, like a warning civilizations, 10, 000 years in the future about like the presence of nuclear waste.

And I think 99 percent of visible, the podcast did a really great episode on this. So forgive me for paraphrasing, but my favorite thing about that. And I just think about that. a lot in terms of deep time and designing for deep time because you’re like there’s a disconnect between like what those civilizations how we could even talk to somebody deep in the future and like it’s kind of interesting to ask yourself like what is like an enduring element of design and like what’s like the same between like even the way we could talk to some like early humans or like humans 10, 000 years away and I don’t know that’s like an interesting question to To think about with design is it’s not even just what’s newest now.

It’s like, what will even endure in like over time? So what’s universal? I don’t know. That’s just like, maybe that’s the high, high above the, like, too thinking too hard about it. But anyway, that’s, this conversation has reminded me a lot of that. Oh, and my favorite, like. Solution that they had was like, what if we breed cats that like glow or they change color in the presence of radiation and that’ll like tip people off in there like called Raycast.

And I’m like, this is my favorite thing in the entire world. Um. Gosh, but thinking on that, so to address the question you’re talking about, like your process of creating like ideas and visual ideas. And so it seemed a lot like you’re kind of starting from a lot of just asking your own questions and starting from pure imagination.

But do you find you’re also using specific research or like current tech to like jump off point? Like what’s sort of the proportion there if you have one? Yeah, uh, super good question. It comes, it comes up often, and, um. It’s a fun one to think about. So, uh, it’s, it’s not, it’s not super specific. So sometimes, so if I’m doing this for, uh, uh, for commercial work, more often than not, the, the client is coming with stacks of research, market research, trend analysis, consumer research, and those kinds of things.

Um, and it’s, uh, it’s often very, it’s, it’s quite dense, you know, they would have spent. You know, a shit ton of money, essentially, because they’re, they want it. They want some basis, uh, for understanding the marketplace that they might be entering. So I do, they’ll do it ethnographic work by that. I mean, like kind of going consumer kind of oriented ethnographic work.

And the, what, what we ended up doing is, is, is a kind of like longitudinal translation of that. So we’ll talk with them. And so this is the part where like the, the visual imagination does something that. Um, something super special. And that’s where the value is. So you got all this research and you got, you got 500 pages in a three ring binder and you’re, and you’re, and you’re kind of doing, you’re talking to their, you know, their main people, their main research people.

Um, and you’re trying to find a way to represent the, the, the, the world or the possible worlds into which this, you know, what this research is kind of signaling just like four or five layers below. The actual research is, is something that you start dreaming about, right? And so I think what, what, what I’ve been able to develop over, you know, doing this for like 15 years, I’m not crying about it.

It’s not necessarily like the greatest skill in the world is when I hear that some of the research you’re talking to people is like, Ooh, that makes me think of. Something we could, you know, something that something that might exist in that world. I think a lot, you know, comes from like being a product designer or just being like, you know, wondering.

So I’ll give you an example. So there was, there was a project we did for very, very, one of the very large times vehicle companies, bunch of research. And we proposed to them, you know, what we should do for the summary of this research, uh, to represent this world as a design fiction, let’s make a magazine from the future.

So we ended up making this essentially like a car enthusiast magazine from the future soup to nuts. The whole thing and I, and actually printed it out. So did all, we treated it like we’re a magazine company. We’ve got a deadline. We got to get a magazine done. And in that you need ads, right? For products.

You need the big, the big brand to, you know, full spread ads. You also need, uh, like little advertisements for, you know, kind of closer to the back of the back of the thing. Like not quite the greatest service. And in that context, I just kind of came to me. I was like, you know what? They’re going to be like.

Not only autonomous, you know, cars and buses and all the things that we want, someone’s going to be like, we need to make autonomous dumpsters. And so I wanted to imagine a world in which these dumpsters, right, because this is how the world goes. It’s not beautiful. It’s conflicted and fraught and oftentimes shitty and things are broken.

Just yesterday, we were driving back from, from getting pizza and we saw one of those little, they look like a Coleman cooler on wheels. You guys seen these things, the delivery thing with the flag, amazing things. You go to, so go to, yeah, go to my, my Instagram. We got the video, Julian. And in this video, this poor thing couldn’t get over a broken piece of.

Concrete. It was, and it tried a bunch of times. I told my brother, I was like, get out and help the thing. He’s like, I’m not touching that. And so this, this is that world. And there was someone else looking out a window from, we saw them looking at the window of the house, just kind of pointing and laughing.

So that, that’s that beautiful kind of eclectic, you know, conflicted, kind of effed up world in a lot of ways, but you know, there it is, that’s the world. So I just imagined this world where there’s these dumpsters and made an ad. For a company, it’s like, you know, we got, we have, we have the, you know, the best autonomous dumpsters, uh, commercial, retail, hazmat, you know, pickup delivery on demand.

And I showed the dumpster actually in a, in a bicycle lane, which drives me nuts as a cyclist, because now we got, now we got, you know, I don’t know. I’m not, I’m not, I don’t have any strong bias one way or the other. It’s like for me as a cyclist, if you’re on two wheels, that’s better than being in four. So that’s my general kind of criteria.

If I’m going to get upset with someone, which I often, I try not to do quite hard. Um, is that you’re on a, you’re on a bike path and then here comes someone 35 miles an hour on a, on a knee and you’re not even a knee bike. I don’t even know what they are motorbike, but it’s, but it’s not, you know, it’s electric motor.

So you have all these kinds of conflicts. So, um, Sarah, the, the, the, the reason I’m describing is, is that the, the, the process, the input, sometimes it’s like the three ring binder of research. Or the, you know, the 73 PowerPoint decks and you use that as a basis, but you use that as a way of kind of marinating your imagination into how would I represent this world in this design fiction way?

If I’m going to do a magazine or I’m going to do, uh, another, another great archetype is an annual report for the company, but from the future, so it’s 2023, we’re going to do your annual report from annual report, your 2020, 2027 annual report. So essentially, we’re going to project four years into the future based on what you’re telling us and where you want to get to, and we’re going to show you what you, what you might actually say.

And we’re going to do it in such a way that, um, it, you know, it’s mostly good up into the right, but there’s some challenges. There’s, there are unexpected contingencies that didn’t, that, that we need to factor in, in order to represent a world that feels plausible. It feels like if you plop this annual report down on someone’s desk, they’d be confused.

Is this right? What, hold on, what year is it? You know, they would be at that moment. You’re not just plopping something on the table where they’re like, Oh, I get what you’re doing. You know, you want them to imagine into the world so thoroughly. So same thing, like when we did the magazine, you could, you could put it on a, in the waiting room of a dentist office and you’d get these puzzled.

Look, people were like, Whoa, wait, is this happening already? I didn’t. Which magazine is this? You know, you have that same, that same beautiful feeling that oftentimes we try to create with visual with, you know, if we’re trying to do something superlative visually, it’s like, Whoa. You know, if you, you’re doing your Mo track stuff, look at that crazy car.

Where is that? You know, but you just, it’s all, you know, composed and we’re doing it not because we want to fool people, but we want it. We want it. We want to make them feel that sense of, Whoa, this is cool. And once you get people at that, Whoa, this is cool. You know, they’re really feeling something. Then you can enter into a conversation with them that begins to get them to imagine what the world would be like if, if, you know, Renaissance perspective or a way of drawing.

You want them to wander into it and not feel a sense of like being antagonized or worse. When we show them, you know, the cyberpunk burned out world be like, Oh man, really? This is what the future is going to look like. I’m not ready for this. Can’t we do something? Can we get our act together and address some of the, you know, the real big challenges?

And so my rallying cry for us as visual designers. is to, is essentially like, let’s, let’s represent the worlds that we actually want to inhabit. And if you really want to inhabit the burned out husk of a, you know, cyberpunk world where we all have to wear rebreathers and we’re all, you know, uh, stocking up on 7.

62 millimeter ammunition because it’s going to be a fight, then I don’t know. It’s not, it’s really not helping. Because we will get that world more. We kind of feel into it. It’s almost that thing of, uh, Um, as a, as a, as a cyclist who sometimes does technical rides. If you, if you stare at the rock, you want to avoid, you’re going to hit it.

Exactly. Right.

Sam J: Like what they tell, um, you know, uh, patients who are You know, geriatric troubling trouble with falling. If they look down, that’s where they’re going to end up. Right? Look up and ahead. Um, and just to touch on a few things that you mentioned the, the, uh, these autonomous delivery things that couldn’t make it over the sidewalk.

It’s like, I don’t know if any of you been to stop and chop in the last couple of years, but they have this the worst thing imaginable is this this thing. I think they call it Marty. And it’s this robotic grocery store assistant. I don’t know what it’s actually intended to do, because all it does is get in your way as much as possible.

If you’re in an aisle, and you’re trying to pass this thing, it’ll literally move in front of you, because of how bad its programming is.

Julian Bleecker: It’s like,

Sam J: imagine the design future of, of the, You know a supermarket then you can’t get anything because it’s all automated In the worst way possible, and I think that that feeds into that, that dystopian thing of, I think part of the reason that movies have gotten to be that way is because of what we were talking about earlier, where it’s kind of easier to write a negative story, right, even in journalism, it’s always easier to pitch and sell a negative story, and it’s like, it’s easier to imagine a bad guy that we need to fight against, So, Yeah.

Or a bad world that we need to fight against than to imagine a good world that we want to all create together

Julian Bleecker: uh That that’s that’s the thing that we’re um mark you’re saying it’s it’s hard. It’s hard. It’s hard because there’s no there’s no Uh, we haven’t seen enough of it to make it feel easy. And I think the the hard bit So there’s a, there’s a famous quote from, uh, Frederick Jameson, where he says, easier to imagine the end, the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism.

He was writing a, it was kind of political theory. Um, but you could, you could substitute a lot of things in there. And I think that’s, this, this is my, this is my new kind of catchphrase. Actually, you know, it’s, it’s telling that the URL for this was not registered. Um, I registered it, uh, Like a few months ago, I was like, what?

Imagine harder. It’s time to imagine harder. We need to do the work and we need to do that. That thing that seems to hurt that where, where you might feel like, you know what? Uh, forget it. This is too hard to do. It’s almost like learning, like, like the first time you decide you’re going to jog. It sucks at first, but you know, there’s some value and benefit in it.

And if you keep doing it, it gets easier. And in, in the getting easier, it becomes beautiful. You’re kind of like, I was at a point where I thought this would suck. And now I’m at a point where it’s like, I want to do it every day and I want to go further. And I think it, we, we need to kind of get into the mentality and the mode, or, you know, my suggestion is we do that with these kinds of things.

It’s time to imagine harder. It’s time to imagine more habitable futures and how do we do that? I mean, as visual designers, it’s like we partly we have the key, which is we have this ability to translate and represent these worlds and it doesn’t, you know, it’s not like a long essay or a manifesto or whatever it’s, it’s visually.

And when people see that, like that’s the first thing that kind of taps in because you make people feel something and when you make people feel something. Then they want it, they want it, they want to dig into it more. It’s like, it’s, it’s, it’s like, you know, how our decision making works, right? It’s like, we see something, we’ve decided we want it, you know, just talking about like products, we decided we want it.

And then we go through the process of rationalizing it. How much is it? How much is away? Can I get it tomorrow? You know, all those kinds of things that, you know, there’s another project we need to work on, which is like, uh, the future of the alternative to consumerism. But, uh, that’s another time. I see

Sam J: Collins has a question.

Yeah,

Julian Bleecker: actually, Sam, I was thinking, like, everything you guys are talking about right now,

Mark Cernosia: and how you, like, uh, propose,

Julian Bleecker: like, it’s very, it’s a lot easier to, uh, see, like, dystopian futures, whether it’s, like, sci fi movies or whatever, um, I think that actually kind of aligns with, like, design thinking, because we’re, like, we’re, a lot of times we’re doing, like, problem solving, so it’s almost like you could use that almost as, like, fuel and energy to then almost, like, think One layer deeper of like, well, what are like the solutions for these like dystopian futures as

Sam J: well.

Yeah. Yeah, that’s great. I think actually, there’s a really good example of that that’s happened recently with grayscale gorilla. You know, they put out this pack of recycled materials. And it’s like, whoa, all of a sudden, you know, we’re, we’re constantly using, you know, metal and, uh, you know, plastic and all this stuff in our renders.

And stuff that is having an ecological impact on us because of all the processing that it takes and how much, you know, recycle how much plastic ends up in our ocean. And so I think that’s a great example of them actually having potentially a positive impact on our future. By playing that imaginative game and putting out these materials for MoGraph artists to be able to show the world, uh, more recycled products and materials in, you know, AAA, you know, commercial features, right?

That, that they have this kind of idea that Nike can show a product and sell a product. Based on a, uh, piece of motion graphics around a recyclable soul or a previously recycled soul. Um, and so I think that seeing more of that, seeing the people who are creating tools for the industry start to interject this sense of like, how can we make an actual ecological difference by giving creators tools?

That lean into the future that we want to see them create. Uh, and so, you know, I, I’ve seen texture packs of solar panels a lot, because that leans into that sci fi thing, but what other asset packs, what other materials could we represent of a future that we do want to see, rather than cold, hard concrete bunkers?

Right. And that’s an opportunity for us to think in design fiction and start interjecting more of these things into commercial that are exciting and that make people be hopeful about the future and leave that positive impact. And it’s like, Julian, what you said is. You know, it needs to trigger that, that feeling, it’s a peptide release, right?

It’s a chemical reaction in your brain and once you felt that and get turned on by that, you’re going to be looking for more

Julian Bleecker: and more of it. Yeah. And I think the, the, the also just to, to build on that and, and tie back to Mark, what you and I were talking about, it’s like, there’s an opportunity to create a visual aesthetic.

I mean, how many times in your career does that happen to be able to sort of like, you know what, we’re just gonna represent this, this new aesthetic. And, um, that, that is a, I think that’s just like a wonderful challenge. What, what do we want it to look like? There was, um, I mean, solar Punk’s really fascinating to kind of consider, ‘cause I think it’s, it as a narrative form and a val and a vibe, a sensibility and, and maybe even like a politics.

It’s, it, it needs, it, it that there’s an opportunity there to kind of create that, just like. There was, you know, someone created the cyberpunk aesthetic. Um, I, it’s, I don’t know if this is the case, maybe it doesn’t matter. Like, was it first, was it first a story, you know, with, uh, that Bruce Dirling and William Gibson wrote, you know, like Neuromancer and Bruce did Burning Chrome and all that.

Was it first a story that then, that, that they described? What was, what was the famous opening line from, from Neuromancer? The sky was like a television set to a. Something channel staticky looking that that’s just, that’s, that’s, that’s prose. And then someone, you know, then you, you want to create, what does that rep, what does that look like?

Um, and you know, I, I don’t know, I don’t know what the first, what people would argue and get into fistfights over what the first cyberpunk pill was, but let’s, let’s call it, you know, let’s call it Blade Runner. Um, and so you got to, that was, you know, that wasn’t, I don’t, you couldn’t call, I don’t think you’d call Android’s dream of electric cheap.

Do Android’s dream of electric cheap. I don’t think you could call that cyberpunk. Could you call it cyberpunk? It

Sam J: edges on that. It definitely introduces some of the themes. That became familiar to that genre. Yeah. Um, but also when, when you said solar pump, it made me think of retro futurism. Yeah. And that’s an aesthetic that I think like would be really great to explore that I think will pick up on the excitement of things that the audience is looking for, but moving in a positive direction.

Cause if you look at retrofuturism, it has a lot of those. The bright colorful elements, but it’s done in a way of like, oh, there are, you know, parks in the sky, right? It’s like, it’s built around this idea of like, uh, you know, creating a harmonious kind of relationship with the terrain and the environment rather than a destructive one.

Um, and, you know, it makes me think about the, the original design for the World Trade Center, uh, rebuild. Um, they had a competition for it amongst, uh, I think 12 architecture firms in the city. And the original winning bid was this amazing glass tower that had parks every 20 floors or so. The full like floor of the building would be a park and would have open areas to the outdoors.

And so, you know, the idea of looking up into the city skyline and seeing trees. In the sky would have been a beautiful, beautiful experience for people and like that this kind of hopeful forward thinking thing, and it got scrapped and got turned into this cement block because, oh, we can’t, we need to make it safe for car bombs.

It’s like they were imagining the worst possible scenario and designing from it instead of like thinking about bringing something to the table that would make people feel positive about it.

Mark Cernosia: Yeah, I, you know, I have a, just a thought too for Julian, you know, in this day and age to, you know, thinking about design in the future and whatnot, like we can talk about cereal boxes and this, you know, all the kind of physical, tangible things, but are you going through certain exercises or anything now, uh, about like designing for a livable future?

I mean, we all know, like. Climate change is real. Like there’s a lot of things that if we don’t start thinking about that stuff. Um, we’re going to kind of be playing catch up, right? And scrambling to figure these things out. Um, are you doing any work within like, you know, climate change or just like, you know, things that are just a global, um, um, I guess, problem at this point.

And what are you doing to like, think of different design systems or whatever that might help? Combat

Julian Bleecker: that. Yeah. So, so that’s a really good question. Um, and I, I wish I could say that I’m, I’m solving the problem, uh, . I, and I’ve, I’ve come to realize that that part of what I’m, I’m good at is, is, uh, is essentially what we’re doing here.

So trying to find the way to make, to help people recognize that potential that they have to. begin doing that work. So I’m not, I’m not a climate, you know, um, scientist or, or, you know, I am an engineer, but electrical engineer, but I, but I think what I’ve tapped into, um, and what I, what I think I am, you know, really to be very honest and sound very profound and existential, my purpose, my purpose, As a, as a, as a, as a creative individual, as an engineer, as like an occupant of this planet, is to create this imagine harder movement.

And I really do feel like it’s a movement. I feel like it’s the kind of thing where if you can get, enroll enough people into this project of recognizing the incredible potential of the human imagination. I think we’ve forgotten that. And to be quite honest, I think we’re in a phase where we’re, where it’s easy to be despondent.

It’s easy to just kind of occupy someone else’s dream, whether it’s Elon, you know, Elon Musk’s dream or whatever. And there was a time when we would occupy the dream of what I would consider personally, what I would consider someone who’s really thinking expansively, whether that’s Kennedy saying like, we will get to the moon, Martin Luther King saying like, I dream, I see a world.

We’ve, we’ve lost that kind of that sense of our potential to sort of say, here’s what we want to do and here’s what we’re going to do to get there. And I think it’s just like, you know, Kennedy wasn’t going to, I’m not, I’m not trying to equate my, you know, associate myself with Kennedy directly, but he was like, I’m not going to build this spaceship, but I’m in a place where I can motivate people.

With a speech, with a speech to get them to imagine a world in which we’re going to do this and then get whatever it is, 480, 000 people and, and probably the today’s equivalent of a trillion dollars to hand build a spaceship, this, this, this beautiful craft to get three dudes to, to, to orbit the moon and get two of them to land on it and return safely.

Oh my God. Like that is, that is amazing. And so I’m just, just a quick plug. So that. That’s this book. So that’s my work. My work now is this book’s called it’s time to imagine harder. And essentially, I look at it as a little very humble manifesto, you all of us to think of better ways to imagine into possible futures.

Yeah. And this is, this is the, this is the building on the other book, which is the, which is the design fiction book. So this is, this book is almost like the how, and that book is the why, why is it important?

Mark Cernosia: Yeah. That’s fascinating. And you know, one thing that I. I wanted to mention, uh, a little bit ago, but, um, was the whole topic of AI, right?

Like, it’s a big thing happening in our industry, across all creative industries, I want to say. Um, and. I’m almost thinking that our narrative of AI has been somewhat constructed through the sci fi, cyberpunk, post apocalyptic type visuals in movies, and I don’t know, but maybe there’s a little Bit of truth to the fact that we are scared of that be scared of AI because of what we’ve seen in these movies and oh, it’s the, you know, the cyber Lords are going to take us over and ruin humanity and yet, but like no one’s looking at Oh, well, the AI can do one trillion computations of this DNA strain and try to find the thing that causes whatever, you know, we’re just so focused on like, oh, it’s gonna end our world as we know it.

And it’s, it’s kind of almost fear based. Right.

Julian Bleecker: And that’s, that comes back to the thing. It’s like, we’re, we’re born into that world, right? We’re born into the world where, where, I mean, Kubrick’s one of my favorite directors. I don’t know if you can see, like, I’ve got a whole bunch of Kubrick. Oh, nice. Tons of Kubrick stuff, you know, a bunch of just everything.

The part of that was because when I, when I grew up, uh, we, a lot of books in the house and one of the books was, uh, the making of Kubrick’s 2001. So here I am an eight year old flipping through is one of those rare kind of mass market paperbacks that had a, had a whole bunch of photos in the middle. You know, they, I think they refer to them as, as, as, you know, like photo plates, it was like, it was a big ordeal.

So, so, and I remember just like flipping through that and just seeing all these things. So we’re born into, like, literally I was born into a household that had this book that showed this picture of this, of this, you know, wonderful, you know, ridiculously long film about, about AI and it comes down to it.

And our relationship to it and the conflicts and sort of anticipating those conflicts. And I think that that’s important to do that kind of work, like, which is, you know, part of the aspect of design fiction that I enjoy is like, you can simultaneously show, you know, the whatever, the good and the bad, but you can, you can show them as coexisting because, you know, that’s where we live in.

Yeah. Like nothing ever perfect. Lost the remote. Uh, you, you, you scream at your television Siri, but then you realize, Oh damn, that’s Alexa. Wrong one. You know, all these kinds of, all these kinds of things that happen and trying to represent those worlds in which they come to. So that people are like, okay, here are another, here’s a, here’s a, you know, richer representation of a future world.

You know, full of all these other aspects of it that isn’t just, you know, kind of one sided utopian versus dystopian. But I think when you’re born into a world where, especially just as humans, where we are, there’s a, there’s a certain, I don’t want to call it fear, I think fear understates it. It’s like a, um, Well, you know, a, a sense of, which we’re challenged by the other.

By the thing that is, is not, not us, right? And so this thing that AI ends up being this thing that is almost like, um, the phrase is like, unheimlich, unhuman, but it’s kind of human. It’s like, it’s like this sense of the uncanny, which, which instills all kinds of very confusing emotions. Like we don’t want to burn it quick before it gets, before it gets us and takes us over, right?

Body snatchers, all those kinds of tropes exist in this, in this moment. So can we create representations of worlds with it? Yeah. With, you know, with, maybe we shouldn’t even call it AI with something else that is where people, you know, what folks are doing, I think in many ways, very constructively say like, this is like a, this is, we should be as afraid of this as we should be afraid of a, of a computer modem.

You know, it’s just this tool. Are there ways in which we can kind of represent it in that way? Um, which, which is hard because right now, uh, I’m not going to say that AI is going to be all good by any means, but it’s, it’s. Highly conflicted, Los Angeles, you know, we get people literally walking picket lines against AI, like what, where’s the world that you would have seen that in, right?

And what’s the other side of what’s the representation of it. So, so just to give you an example and maybe back to Sarah’s question. So one of the projects we’re working on is, uh, essentially a magazine from the future of Hollywood. So imagine like variety magazine or some kind of trade magazine, but from the future.

And we’re taking all the inputs and just in, in conversations and workshops that we’re doing, that we’re doing all the conversations to try to represent what would this world look like and feel like, and what would be the, what would be the feature articles about this world from the perspective of Hollywood from entertainment?

Where has it gone? What are the, what are the little studio, little production houses that, that always crop up in Burbank that are just doing like, you know, second and third order production tasks? Right, right. You know, we need wires removed, you know, those kind of outfits, all the stuff that maybe, you know, many of us could call rotoscoping,

Mark Cernosia: like rotoscoping algorithm just to get

Julian Bleecker: rid of that.

And so, and so what are all the companies that are going to crop up to do that and more the things that we’re not even imagining right now. So, you know, we have, you know, so, so how do you, how do you feel into that world and represent it in a way that is, that is, it’s not going to make everyone happy.

Because no one, not everyone’s ever happy, but it’s going to show you like, here’s what this could look like. And maybe for some of the people who are feeling very emotionally, but on both sides, emotional about it because you’re like, you’re messing with my livelihood here and it’s the only thing I know to do.

What are you trying to take that away from me? This is crazy to say like, you know, a bunch of things like when it’s like, you know, it’s, it never hurts to always be skilling up. There are other things that you can do because you’ve got this amazing piece of vascularized meat that millions, hundreds of millions of years of evolution have given you, but don’t take it for granted.

Figure out what the next thing is and feel into it in a beautiful way where it’s like, Oh my God, there’s new potential. I can do something. I can create this other kind of set of experiences and worlds, and I’m going to use the AI to do this. And you know, Oh, someone’s going to write me a check to start a company to do it.

Like I’ve always wanted to have my, you know, all those things looking at as opportunity at the same time, you gotta, you gotta show the other side. Which is where, where, where the things are going to be a little bit broken, like, um, or, or things coming back, like practical effects are back. Now go talk to Wes Anderson.

Mark Cernosia: Totally. Yeah. And one thing we’ve always talked about too, is like with the whole AI thing, yes, it is a threat to our creative livelihood and stuff, but if you’re just going to live in that fear and not taste it and not even participate,

Julian Bleecker: then. That’s it.

Mark Cernosia: I have to say, you’re going to kind of be left behind, you know, when we’re focusing on this new plugin that comes out or this new technology, because it’s going to make us render faster.

No one really seems to care about that, but if it’s going to take away a concept artist board or whatever, people start freaking out there. It, everyone is right at this point. I think, you know, it’s still kind of a fear of the unknown, if you will. Um, but. I think if we’re not tasting it as creatives, if we’re not experimenting and really trying to use these tools for how it could level us up or expose how it’s, you know, going to level us down, like,

Julian Bleecker: and so, so these are the kinds of things.

So in that magazine, you can kind of represent. Those kinds of conflicts. So you can have, you know, like a, like a letter to the editor that, you know, that just said, that just says like, you know, I really thought this was going to be a problem, but you know, like, you know, now, now, now it’s not, you find, you find a way to do it as if, and you can also have the things, um, you know, the other side where, which is like this.

This thing is, it’s, for my opinion, it’s ruined Hollywood back in my day. Why we just, uh, we only had to shoot in 4k and now look at the, it’s all VR. You know, you have those things because that’s what the world’s going to look like. And you also have the things, you know, classified ads in the back to give you a sense of what the jobs might be in the future.

Right. And you’re going to dream into these things. You think of, you know, what do you want? But then also you think about what, what might possibly happen because you know, I’ve lived in the world and I, and I understand the experiences that happen. Like I remember when. When, you know, internet came in and it was like, it was a big deal to get a, get a, get a, uh, 28, eight modem, right?

So totally, there was all this, there was all this confusion. And I remember when I first, when I made my first homepage, I was living in Brooklyn and made a homepage. And, uh, and I remember I was like late to meet some friends, you know, out and I was, what were you up to? I was like making a homepage. And one person was like, why, why would you ever want to do that?

And they said that in the kind of dismissive way. Like this internet thing is, it’s, I’m not saying that, you know, I had any kind of foresight, but there was, there’s that feeling of like wanting to be conservative, wanting to keep things as they are, right. As opposed to looking at the opportunities. And I’m not even talking about like things are going to get better or brighter or greater or easier or whatever, or cheaper or anything like that.

It’s just like evolution is a beautiful thing. And it’s, and it’s chaos, it’s confusion, those moments of like, you know, the molten earth changing its form. It’s like, it hurts. It, and a lot of, a lot of things, you know, um, are challenged by it, but we have this incredible ability again, back to that vascularized piece of weird folded meat in our heads to imagine things otherwise, to imagine the world different, both for us and the world more expansive and finding the way to kind of be like, you know, to, to the point you’re making like it, like always learning, always create and evolving oneself in terms of, you know, one’s visual practice.

I’m gonna try a different aesthetic. You know what? Every Sunday, I’m going to spend two hours. I’m going to play with some of those, uh, you know, in, in, in cinema 40, I’m going to play with some of the new gray scale gorilla materials. I’m just going to see what kinds of things are make. I’m not going to, I’m not going to do another, uh, soda can.

Right. I’m not going to do another, you know, chair. I’m going to just try to build a world. Um, and I, I’ve been doing this for a while. I’ve just, I would call them the headquarters projects, which is making a new headquarters, For the near future laboratory just in cinema 4d, you know, just just as like playing around with what structures might look like now I’m doing a little bit mid journey, which is just

Mark Cernosia: oh, there you go.

Well, you know, this is actually kind of segues really well because we’re We’re starting to hit time to kind of wrap up here But chris put a question in the chat and i’d love to invite him to pop on up. Um on to ask it Thank you very much.

Julian Bleecker: Um, it was interesting as I was writing that question in. We

Mark Cernosia: started into the

Julian Bleecker: AI conversation and Julian kind of wonderfully circled back to bringing us back to that piece of meat and talking about imagination.

And I know, you know, watching over the past year as mid journey has really flourished and has become, uh, you know, a thing we see a lot of like architects, designers, people in different creative fields showing images

Mark Cernosia: that they toyed with in Um, mid journey and things like that.

Julian Bleecker: And there’s a very

Mark Cernosia: unique aesthetic to those AI generated images that is exciting and new and very different.

And I wonder about, uh, not talking about the fear of it

Julian Bleecker: taking over. You know, that’s, that’s, those are big questions, but I wonder about it’s challenging

Mark Cernosia: our, our own creative

Julian Bleecker: capacities. For envisioning those futures, when we’re looking at these stunning, amazing things that

Mark Cernosia: are lacking a story,

Julian Bleecker: but our compiled images

Mark Cernosia: may even have some physics or topology applied to the architecture or something in some way.

It’s like, wow, I wouldn’t have thought of that. Um, you know,

Julian Bleecker: but I love that vision. And so how does that, how do you feel like that may contribute to, or even challenge our capacity to be creative when thinking, uh, in these sort of future forward ways? Yeah. Um, so, so it’s a really good question. Um, and I think that we’re definitely at a point where we’re, we’re fetishizing the pure image, um, that, that, that we see, you know, it’s, it’s very, um, which is very easy to do.

And I think it’s like that beautiful moment where we’re trying to figure out what do we do with these things. So, um, I’ll give you, give you the example that comes to mind, uh, that is when. Um, when I, when I kind of learned through experimentation and talking to people in my community about how to create a particular visual aesthetic with, uh, with mid journey, um, I started doing lots of, lots of vehicles.

There’s also, it’s also, um, sort of on this, uh, little jury of, um, for, it’s called, um, mobile Detroit 2050, which is part of Detroit’s design week, which design month, which is in September. So we’re doing a little bit, just fun exhibition of, of future visions of mobility. And, and so I started playing around with like mobility futures, uh, with mid journey and just ended up doing a lot of vehicles.

And it felt like a little bit wrong to me. It didn’t feel complete because they were just, uh, there were just these vehicles, which is very easy to fetishize. Matter of fact, it, you know, I’m not crowing about it, but it’s like, um, when I started posting on Instagram, like my, my followers grew six fold, six fold.

Right. So it’s kind of thing like, Whoa, like what’s going on. Obviously people are seeing these images and they’re feeling something enough to be able to click the, you know, follow me. I’m not a, I’m not a big social media guy or whatever, but, but I found that fascinating because people are fetishizing the image.

But what I, what I was doing was like, I couldn’t just have the image. It just felt. Incomplete to me as a kind of visual storyteller, I guess. So I started writing descriptions as if these were things that were represented in like one of those, uh, auto trader magazines, you know, like you might get at a, at a, at a convenience store where it’s like, Oh, I wonder if I’m looking for a, you know, a truck.

Or something. And you kind of flip through it and you read these things. And I had, I had some examples of those kinds of magazines. So this, this is like Uncle Henry’s Weekly. It’s from like, Oh yeah, nice. It’s like from rural Maine. And it’s like people selling everything from leaf blowers to, uh, to, you know, like, like a, like an old shotgun.

Right. So, and, and, and in those, each one of those descriptions is, it’s this beautiful story. There’s some words like, you know, Hey, you know, um, I, uh, I worked the third shift. So don’t, don’t, you know, don’t call me too late. You know, you’re like, what does that mean? What, what, what third shift of what? You know, obviously it’s something, there’s something in the idiom of this, where this is from.

People get it wherever it might be. It’s like, Oh, you’re working the swing shift. You work on the 12 to 8, 12 at 12 midnight to 8 AM. So yeah, I’m not going to call you, you know, whatever, whatever it is. And I thought that was, that’s amazing. Like, can I describe these vehicles move away? You know, the image is a bit of an anchor, but it’s the description.

So in 2000 characters, which is Instagram’s limit. Can I describe a world from which these things came? And I didn’t know the world to begin with. I just started writing these things. Just kind of, you know, again, it’s just a practice from years and years of writing described, you know, descriptions of non existent products for design fiction exercises, you can kind of get into a flow to be like, Hey, this is, you know, this is late, it’s, it’s missing this and it needs a new.

Columbator on the tokamak. So you’re just kind of making stuff up. But as you, as you do it over time, I found for me doing these things that I started a world started, started emerging. I started trying to imagine it’s a world. So I started writing as if there was, it was a world that something had happened, right?

The classic science fiction, you know, cold open. Something’s happened to this world’s a little bit different just because of the, what you see around you, you know, in the story, but it looks, otherwise it looks okay. Like they’re making food. They’re not, they’re not running away from aliens, right? Some, but something has happened.