Contributed By: Julian Bleecker

Published On: Thursday, December 24, 2020 at 12:25:00 PST

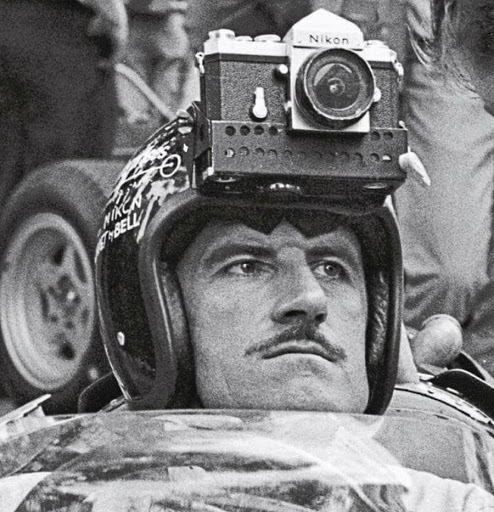

One - The Nikon F vs The Telephone

A blind spot in modern user-centered design is the difficulty in handling the ‘unintended use case’.

There was a day when designing a ‘hard’ product like a physical camera or a ‘soft’ product like a web page had a small range of possible uses and the universe of use cases and unintended consequences was quite small.

This blind spot is particularly at issue as the complexity of designed products and their contexts of use grows. Subsequently the resultant universe of possible designed-for as well as unintended and unexpected use cases becomes unwieldy.

Back in the day my first camera could only take a photo by exposing light onto ‘wet’ film. Neither the camera nor the film knew where that photo was taken. My camera didn’t store that image in any way other than on a long strip of a chemically-schmeared bit of plastic film. That film was most always in my possession and no one else got to manipulate or abuse it (I processed my own film, as much for the pride of doing so as for convenience.)

My images didn’t get lost, kidnapped or turned around in the grimy back alleys of a digital network. They weren’t harassed and harangued by disruptive ecosystems. No one’s ne’er-do-well idea of ‘innovation’, nor some start-ups miscreant algorithms got their paws on it. There was no real meta data associated with the images. Meta data wasn’t even a thing really - although I suppose I would sometimes keep a paper notebook of exposure settings and such all, but I didn’t do this often. Once I had what was called a “data back” for my camera that burned some of this exposure information onto the film proper. That was about as far as it went to squeezing any other ‘value’ out of a nice photo other than a nice photo.

Back in the day, If I wanted to share the photo I would have to print the image, and literally give it to someone, perhaps in a handmade photo book. In any case, I always knew who I was sharing the images with.

There was no direct nor easy way to learn or discern much more that wasn’t deliberately shared, such as who or what happened to appear in the background, a street address, car license plate, etc. The photo was a photo and the purpose of the photo was to capture a moment of life’s experience and communicate as much through the composition. And, as it turned out, that was enough.

And then cameras became digital and that held forth the promise of something — convenience I suppose? And telephones became cameras as well. Eventually telephones would became mostly cameras that sat at an endpoint of this crazy distribution of algorithms we call the Internet. And companies that made the components that went into cameras that were just cameras started disappearing and the largest ‘camera’ companies were now companies that make telephones.

As a life-long and earnest amateur of a photographer who’s also a contrarian-optimist technology guy my first concerted effort at a website was to build a photo library of as much of my wet photography as I could. I bought a film scanner at B&H in Manhattan (I walked there, bought it, and walked back to my apartment with my own, totally human feet) at some consequential expense and wrote an AppleScript that would automatically scan the negatives to an Iomega Jaz drive. I figured out how to make PHP (I think it was PHP, it might’ve been JSP) show the photographs through some cataloging system of my own design. The process of building it was, it turns out, more engaging and generative than actually having it around to use.

Having grown up passionate about photography, and being decidedly an optimist about the potential of well-mannered and considerate algorithms to beneficially mediate and enhance experience, the idea of images scurrying about on networks is super cool. I’m also at the same time an incisive contrarian and can simultaneously see the unspoken problems with this. After all, not all of the algorithms you meet while meandering the networks are considerate, well-meaning, nor are they looking after anyone’s best interests other than their own.

It is both useful and dangerous and thereby odd that an image can travel around a digital world along with my name, the type of camera I used (and maybe even, with a serial number, the camera I used), a small cache of my personal information, the precise time, date and latitude/longitude at which the photo was taken, never mind the photo image data itself. It is simultaneously intriguing and terrifying that there’s more information than I realized in that image that some end point will algorithmically tear down to determine who else appears in the image, whose car can be seen in the background, who just stepped out of the alley back there. Etcetera.

The point here is this: as the opportunities for designed use cases increases - like the camera phone with all of its ‘meta’ - the complexity of doing good, meaningful design work increases exponentially. This thereby increases those unknown knowns - the things you know are made possible because of increases in complexity, but you don’t bother to mention, or you can’t be bothered to mention, or are told not to bother mentioning. Even naming them becomes taboo because there’s ‘real work’ to be done. And/also no one likes to use the ‘p’ word in polite company.

Limiting the camera use case to composing, focusing, pushing a button, and confirming the ‘sharing’ ritual would seem quite natural when you’re following some formalized process for designing an app to take photos. But the platforms and that back alley of the network have become wildly complex, allowing for many more possible outcomes, some if not most of which lead to peculiar, unexpected, indelicate use cases.

At some point we begin to substitute ‘use case’, which sounds ever so polite and full of intent and purpose - with the phrase ‘unintended consequences.’

These unintended consequences are the situations that we either legitimately didn’t expect to occur, or don’t want to occur, or expected might possibly occur but we decide to ignore because, I mean..who really wants to talk about how your earnest bid at having your billion dollar app idea for a new photo sharing service will quite possibly end up as a hook-up platform or some other decidedly more salacious and awkward, you know..consequence.

I wonder how many of these unintended consequences are simply outcomes and possibilities that are known but unexplored? Or how many are simply difficult to describe and discuss because the design tools and processes in use do not know how to stray into the realm of the unknown knowns - the things we know are out there as possible (even likely) but for which we have no constructive way to identify and discuss.

How do we get to know these better and perhaps utilize them as opportunities for better design, unexpected benefits, or even to simply account for them in the design work so we can honestly and transparently come to terms with them? (I perhaps naively hold on to the principle that honesty and transparency in matters such as this are a good policy. Same with ‘owning’ bad outcomes. Although Midge and Roy upstairs in Legal might have a different way of seeing the world insofar as uttering the possibility of bad outcomes implies you knew about it and did nothing to avoid it. Eck.) And when does an unintended consequence become a known known — meaning it can be somehow managed in the implementation?

Two - Design Fiction for Unknown Knowns

I’ve mentioned this a few times already - what do I mean by ‘unknown knowns’?

This came to me via the entertaining Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek who was was musing on the unspoken fourth possible construction in the Rumsfeldian canon of epistemology. You can read about it in that link, but it might seem extraneous to the topic if read in that context so I’ll try my best to explain how I read it in the context of this design topic.

Briefly you might recall that Donald Rumsfeld, lecturing from the Department of Defense lectern, offered his take on the consequences of knowledge in a miniature primer on epistemology.

Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.

Žižek in his form points out that there’s one category missing - the unknown knowns.

Unknown knowns are the things that we know about, but cannot admit to usually because we don’t have the means or capacity to own them, or admit to them, or even utter them without feeling out of ourselves, or feeling embarrassed or shame or for some reason we can’t quite put our finger on because putting one’s finger on it is taboo. These are things disavowed, like that squirrely uncle with the walleye that you know you have but, for some unknown reason, you’re not allowed to mention, certainly not around the dinner table. In the context of tech or product design It might be the way your product is used for something you find abhorrent or against your beliefs or values, or something that, if admitted, may identify you as odd or out of the narrow boundaries of ‘normal’ in the tech world. The violating and deleterious aspect of tracking and influencing individual’s behavior might be one of those things, just as one elephant of a reason.

Unknown knowns litter the design-tech world as unintended consequences or unmentionable things. But, if we are to do a good job at being futurists and designers and strategists and thoughtful on the topic of possibilities even if they lie outside of our own sense of, well..what makes good sense, we should not allow these things to go unmentioned, beyond consideration, or dismissed as irrelevant.

But, if it’s not already clear, I believe we need to find a way to include them in our work more deliberately. But why would we do this?

Well, if for no other reason than completeness. But, more importantly - if there are outcomes we genuinely want to avoid, we need to be able to say their name, codify them, and then do our best to design and engineer for avoidance.

Design Fiction can play a role in these situations if it can become part of whatever design process you may be employing. This is because it enjoys playing with awkward moments - like the broken Pine & Oats cereal box I talked about in the last episode.

What that moment in Minority Report did for us was provide an easy point of entry to consider something everyone at the (hypothetical) Pine & Oats Cereal Box Design Team Project Kick Off Retreat knew could happen, but had no real process-oriented way of introducing.

Three - You Left Memaw Where??

When I was a kid my parents gave us a choice for magazine subscriptions once a year. I’d flip-flop between Mad Magazine and Byte Magazine, but mostly Mad because I could read Byte at the local public library. Maybe this is why I happen to enjoy clever satire in my design-engineering work, I don’t know. It’s the only thing I can figure. In any case, I find satire useful in these tricky, intractable design-engineering contexts.

Why is that? Because I’ve found that humor lubricates the conversations around awkward or otherwise challenging topics. If you can get oh-so-serious folks with their perfectly knolled design documents that suggest they have everything figured out to crack a smile or even chuckle, then you’ve softened the ground a bit for a good discussion of where their brilliant idea falls comically short. To this end, I often look for opportunities to describe these disavowed circumstances with a bit of good old-fashioned humor in order to lead the conversations that will hopefully yield better, richer insights and farm-fresh perspectives that I think one should expect from honest, hard-working design-technologists.

I told you that story so I can tell you this story: several years ago Nicolas and I led a workshop focused on the topic of self-driving cars. To get into the topic we decided to use the Design Fiction archetype of a Quick-Start Guide. You know those things. They’re the guide that briefly explains to a new owner how to use, or configure, or screw together whatever product or service they’ve just burdened themselves with.

The overall purpose of the workshop was less about creating a QSG than it was to introduce how Design Fiction can expand our imagination on a particular topic to contribute to the benefits of other design protocols and processes.

The QSG is a great design challenge. I can see its utility as a Design Fiction for most any product design endeavor. Through it you have to explain to a novice how something is meant to be used - and do so with the briefest possible explanations.

To prepare ourselves we looked at a whole bunch of existing Quick Start Guides to study the archetype. We noticed that some of them, particularly ones for cars, include a Frequently Asked Questions section - a great container of possible unintended, peculiar, unexpected, use cases. FAQs represent the situations that no one really anticipated but have been found to occur when the product or service in question has been in the real world, subjected to the whims and vagaries of real humans (not ‘users’, as most design processes describe) who, for any number of reasons, do all kinds of remarkably odd things or get into peculiar, unexpected, unanticipated ruts, snarls, and snags with the ‘workflow’ — which worked fine in the lab and maybe even in ‘user’ testing..but not in the crucible of the normal, ordinary, everyday human world.

During the workshop I was assigned to put together the FAQ section. My approach was to think of the odd situations that might occur with self-driving cars, which is, if you think about it for about a nanosecond, not that difficult at all what with my extensive and exhaustive background in Mad Magazine style satire.

As the workshop proceeded a kind of ‘Taxi Mode’ that we branded variously ‘Uber EverDrive®’, ‘Intuit NeighborShares®, Amazon ¡TaxiTaxi!®, Amazon PrimeValet®, and CarShare®.

It was imagined that these were kind of like a plug-in suite of platforms you could subscribe your car to by which your self-driving car could go out into the world and earn a bit of money for itself, for the plug-in provider, and maybe a wee little bit of cheddar for you.

Fine. No brainer, right? Someone might even think this idea of an ‘Uber EverDrive®’ is innovative and clever and disruptive and, you know - with a few more futuristic things like this that come out of the workshop we’re done by 2 and we can all break for the local TGI Fridays for Jalepeño Poppers and beer.

Nope. Not quite yet. That’s not the work.

In a world where nothing ever works precisely the way it was intended - like that futuristic box of cereal from last week - it wasn’t hard to imagine possible unintended consequences that might be useful to represent and discuss.

Just imagine personally owned self-driving cars being sent out on their own in Uber EverDrive®. It’s already a riot of whacky unintended outcomes and situations ripe for click-bait-y reports and little preposterous video memes.

I thought that eventually, inevitably, someone is going to get accidentally left in the back seat when the self-driving car gets sent off this way.

You know — Memaw fell asleep back there and, like..you’re distracted by your kid’s annoying pleas for more Pine & Oats brand Vanilla Double-Stuff cookies or whatever and you have two bags of groceries to schlep and the dog clearly needs to poo, so you’ve completely forgotten she was back there and so, well..now she’s asleep in the back and on her way with the car in Uber EverDrive® mode to downtown Temecula to pick up some 12 year old kid who’s going to a friend’s house after soccer practice. Stuff like this is going to happen. Definitely.

But how do you represent this? What’s the point of entry for this that makes this particular scenario useful and that makes it a productive conversation starter?

I settled on an entry in the FAQ

So, what I’m saying is that unknown knowns are a category of outcomes that are often not diligently accounted for in the work of design. Accounting for them may seem useless at first consideration. Beyond the ostensible utility of doing the design work.

I would argue that Design Fiction embraces the generative function of this sort of useful uselessness — a kind of uselessness which has the strong possibility of discovering things that would have otherwise been left unknown.

Right?

Next week we’ll work on long division. Bring a sharpened No. 2 pencil.

A brief end note which is to say that I host weekly Office Hours where we talk about these kinds of topics. They happen every Friday at 9am PST / 4pm GMT. Great fun group and the topics never fail to amuse and engage us all. If you’re interested in the short and sweet reminders I send out, please become a Patron over at https://patreon.com/nearfuturelaboratory.