-

Most times when we hear about something that has no solid meaning, that has no firm arrangements of connected neurons within our brains, or particularly something we have never ‘seen’ or ‘heard’ or have experienced first hand, we ask, ‘what is that?’ or ‘define that for me?’

-

Making sense of something new is to arrange it such that way that it is sensible, that we can feel what it is, how it operates, when we might use it, how to put it on, how much it generally costs, what it takes to make it, when we use it to describe a set of conditions or circumstances, what saying it makes us feel, what saying it makes other people do. Etcetera.

-

The sense-making definition of design fiction is to consider the ways that material artifacts — things considered, designed, made, produced in the material sense of things — can structure and arrange our understanding and ability to make sense of sometimes vague, nebulous notions of the future.

-

If we take it as a given that ‘material culture’ says as much about a moment in time as the more direct, spoken, authorial declarations of the cultural zeitgeist, then

-

It would be entirely useful to use material culture in a similarly declarative fashion.

-

Why is this?

-

Well..

-

Consider all of the ways we interpret possibility, just even in the ‘commercial’ context, where teams trying to innovate use a variety of mechanisms to make sense about what they should be doing to prepare for, create, operate in any of a range of possible futures.

-

((* That’s another way of saying that we have a huge range of approaches, tools, procedures, protocols, step-by-step processes, partner agencies, departments, certificate programs, etc., all to help us answer this question: ‘what should I do?’ — a question that creates fear in the hearts of all souls whose job requires that they answer that from time to time. *))

-

So what are some examples of the many ways we interpret possibility? Along with all of the prose-based writing about the future, we might also consider:

- experts’ speculations about what the future might look like,

- interpretations of the implications of trends reports

- the thick (that is, fancy and expensive) research reports from McKinsey, BCG, and similar kinds of consultancies both big and small,

- the best interpretations of economic futures from the team in the Projections & Crystal Balls Dept., that is to say — financial planning through peculiar tea leaf spreadsheets and mathematical models embedded in Excel both simple or ‘complex’, like projected costs/earnings/sales/profits/guesses — all of which are kinds of speculative fictions about the future lest we forget,

- the ‘evidence-based’ insights from the strategy team on the 4th floor,

- the quantitative charts, graphs, and tables from the consumer research study program from the folks over in marketing,

- a ‘deck’ of qualitative ‘write-ups’ from the interviews, in-home visits, video interviews, ethnographies (woops..) from that quirky insights, trends, and innovation agency which always seems to have at least one team member with a British accent,

- a bunch of made-up ’scenarios’ of little moments and something called ‘personas’ that are like these character sketches that remind me of baseball cards, done up by someone who probably wanted to be a screenwriter or novelist, and beautifully visualized by someone who probably just wanted to have a small studio and make meaning by making art, but rents in this city are like, ooofaa, so..,

- an email with a link to a TED talk someone helpfully spam’d to the entire team’s email distribution list with the unhelpful subject line ‘Check this out’,

- a clipping from a newsletter, an article from Bloomberg, a podcast episode,

- the didactic book jacket style ‘thesis’ of the latest business and strategy-type book that everyone says they’re reading but, you know, that 30 word jacket blurb basically tells you want you don’t need to bother reading, so,

- an impromptu moment in the break room where a plot point, or scene, or weird artifact from an episode of Black Mirror (or Minority Report, or War Games, or Her, or West World, or etc.) is discussed,

- something Elon said,

- something Bezos said,

- something Andreessen said,

- tarot cards,

- future vision videos,

- a dizzying and mind-numbing wander around CES,

- a design thinking workshop,

- and etcetera.

-

All of these and even more both formal and quite informal ways by which we try to get some feeling or make some sense as to what is next,

-

What I am suggesting is to add to this a clarifying dose of material culture

-

Not just reports, analyses, PowerPoints, pie charts, vision videos, and consumer studies.

-

But a translation of all of that in the form of artifacts. Things ‘found’ in the future, as if exhumed by some kind of time-traveling archeologist.

-

What do I mean by ‘translation’ of all those reports and stuff?

-

It’s to answer the ‘so..what?’ question implied by all of that other stuff, which is this: what do these futures look like? What do they feel like? What are some of the things I might find in my cluttered garage, or in the cup I’ve shoved into the cupholder of my flying car (what do I drink on my commute? do we still drink coffee in a future where we’re hyper sensitized to the carbon impact of everything? or are we now onto a delicious simmering caffeinated protein slurry?), or indicated in the Terms and Conditions of the blockchain enabled trash bin just outside the corner convenience store where I exchange my crypto for the really good, dark market chocolate? What is implied by those macro-scale expensively reported, bar-charted futures? What are the implications as stuff, not just words and graphs? The ‘so…what?’ that is lurking in your thoughts, just below the surface of all that evidence-based data, the qualitative insights? Design fiction answers that question.

-

“So…what?”

-

Design fiction answers that question in a material cultural form. With artifacts as interpretations of that future.

-

Now to the question: ‘Where’ is design fiction amongst all of this?

-

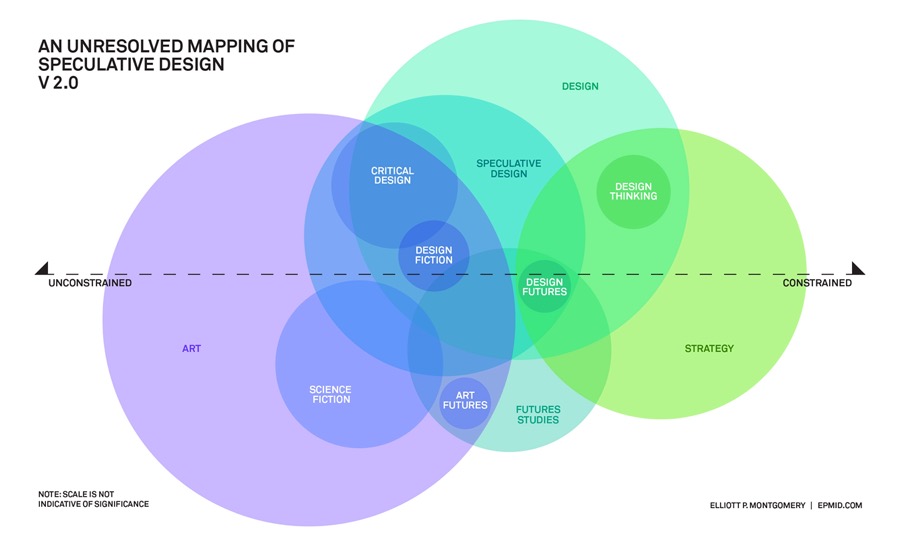

I’ve been building upon Elliott P. Montgomery’s fun ‘Unresolved Mapping of Speculative Design’ in order to situate where design fiction might live in relation to other ways of making sense of possibility, or of making sense of possibility as pertains to the near future. (Elliott and I discuss this in Episode 041 of the Near Future Laboratory Podcast)

-

I copied Elliott’s graph (above), pasted it into Miro, and began to interpretively redrew it to give myself some room, holding on to the general architecture wherein ‘Art’ was on the left, and ‘Strategy’ was on the right. (When I have time I’d probably reverse that to coincide with the ‘left brain’ vs. ‘right brain’ interpretations, maybe.)

-

I then started adding labels to give a sense of what kinds of activities fall into what parts of the graph

-

((* To echo Elliott’s caveat in his blog post on this, do not interpret size, color, orientation as explicitly meaningful. This is a graph that you ‘feel’ rather than place bets or start fist-fights over, okay? *))

-

As I started adding these labels, I started really comprehending the huge number of ways we end up using to make sense of the future.

-

I kept adding stuff. I talked to Elliott about stuff. We riffed back and forth first while sharing pickled vegetables in Chinatown, and then in a Zoom call.

-

This is where I’ve gotten so far — effectively design fiction is in the intermediary between the practices and approaches to sense-making that operate from feeling, intuition, imagination — the right brain — and those that use evidence-based and scientific-based sense-making methodologies, generally attributed to the left brain, the lobe that does its best to strip away feeling and reflection and interpretation of lived experience for austere structures and just the facts, m’am.

-

There’s much more to be done here,

-

but the insights I have been feeling over the last few weeks is that design fiction works precisely because it brings in a special kind of interpretation of all the things on the right side of the graph and,

-

it does this specifically through synthesis/interpretation/translation of those analytic things into material culture —by making the things (that’s the ‘design’ in ‘design fiction’) that might be in the world that all the reports and stuff are grasping at.

-

Design fiction is a way to declare some aspect of a possible future through implication.

-

A declaration not through prose, or a PowerPoint, or a graph, or a three-ring binder filled with page after page of analyst reports,

-

but through something as simple as a printed newspaper sports section (from the future) giving the results from yesterdays AI-enabled virtual basketball league; a printed sales brochure (from the future) for some blockchain enabled refrigerator; an unboxing video (from the future) for Kanye’s new AR glasses for YeezyVerse,

-

etcetera.

-

These are material cultural artifacts from the near future.

-

These are not stories about the near future, at least not in the pedestrian understanding of ‘story’.

-

These artifacts described just above? They could very easily go along with all of the other (more quotidian) ways that strategy, research, and innovation teams come together to figure out what’s next. The strategy, research, and innovation reports — the trends analysis, the research reports, the qual/quant studies — function more as ‘evidence’ or ‘rationale’ and go hand-in-hand with the design fiction artifacts.

-

This all operates together.

-

What I am arguing for design fiction — what myself and others have been arguing for design fiction since 2008 — is to bring these things together to create a richer basis for decision making. Mix the ‘evidence-based’ and the ’analytic’ and the ‘just the facts’ stuff with the ‘intuitive’ and the ‘imaginative’ and materialize that mix in the form of artifacts.

-

Design fiction brings a particularly expressive richness to the interpretation. It gives teams a chance to ‘feel’ and ‘handle’ the future. Design fiction artifacts become touch points to the future. They are not gee-gaws or things done ‘just for fun’.

-

We should keep these ‘artifacts from the future’ around us, constantly updated so we can interpret the worlds to come and make sense of where we are going. (** Not all design fictions are symptomatic of an unrealistically utopian future, remember. **)

-

Design fictions are generative and additive. They start the imagination going in a way a trends report simply does not. (Differently, if not better or worse.)

-

Just remember, design fiction artifacts are things that imply the world, not stories about the world that happens to have things in it.

-

You have to make a thing. Not just write a story about things.

-

Writing fictional stories with things is basically science fiction, or maybe science fiction prototyping.

-

Don’t let someone tell you it’s design fiction. If they do, they may be legitimately confused and you should see about helping them understand more completely, or they may be interpreting things without having gone deep on the last 13 or 14 years that design fiction has been finding its way.

-

Or they may be trying to sell you a bill of goods, or following the latest “futurists” trends because they hitch themselves to whatever ideas happen to be trending.