On Wednesday (that will always have been February 28th 2024) I spent the day at Chapman University at the invitation of the Department of Art to give the annual Bensussen Lecture in the Arts Series. Many months ago Justin St. P. Walsh, who is a Professor of Art History, Archaeology, and Space Studies (🧑🎨👩🏽🔬👩🏽🚀) asked if I would do it and so I said ‘yes’, not at all knowing what I would lecture on to backfill something that belongs to a series of lectures. No idea. But, I like these kinds of things where I genuinely have no idea, but know something is always percolating. In any case, it would be a tab in the calendar where I would have to develop something presentable from the swirl of book ideas and project topics rather than letting them just swirl around in a mess of thoughts.

((Parenthetically, it just occured to me that having that kind of external forcing-function to come up with a cogent bit of material is part of my process as I just recalled that the keynote presentation I gave at the AIGA two years ago (!?) unlocked the structure and outline of It’s Time To Imagine Harder. I got such encouragement from that material in the Keynote slide show that I set out to blog about it, and then thought I should write a little compact pamphlet, which is basically an elaboration of the Keynote slide show only in portrait orientation and with more words. Its reading time comes in about six times the time it took me to present it.))

Back to Chapman: It was a truly awesome, invigorating day spent with students in classes where I came to find out that Design Fiction has been long integrated into many of the faculty’s course syllabi, and many of the students had been drawn to the methodology in their own studio practices. Super gratifying to know the Near Future Laboratory’s work and practice had meaning and natural value.

I sat in on a class that has been working through a brief to do some worldbuilding with Design Fiction for a world in which human-plant interaction was a normal, ordinary, everyday thing, I suppose different from whatever one may associate that with today. It was an awesome opportunity to improvise around what kinds of artifacts one might see in that world — a sun-bleached sign in the window of a small florist advertising a particular feature of some branded breed of rose that changes color when people are in the room, together with terms and conditions for use and warnings against downloading the DNA; a little instruction card for a potted succulent in a delicate little ceramnic pot that comes with batteries and an antenna; this kind of thing, and then toss ideas around with students and watching them start to light up as they got into the stream of ideas and started wandering around this little florist shop we imagined. Super fun.

The conversations made me think of a continuity of spirit from an early days NYU ITP project that an old friend Kati London and collaborators did called Botanicalls back when the internet was fun and weird. It’s not a ‘new’ thing, and I made a long preface to one student who shared their idea that came out of a series of super short, super timed micro sprints during the class I was sitting in. The long preface was to say that what has been, will be again, only I didn’t say it in the fashion of a poetic Talmudic incantation. I was trying to find the way to be sensitive to the sometimes fragility of the creative spirit which is to, at times, prefer to consider the spark of ideas it has to be unique and worthy on their own, and not amongst of trajectory or territory of ideas and their materialization. That is — a collaboration of kinds of dreams in the form of ideas, projects, reflections, and articulations of those dreams in various guises, including things that have happened before one has had one’s eye on the field.

There is something I used to do when I was a Professor at USC’s School of Cinematic Arts, teaching interactive technology to MFA students which was to require that they do a bit of a bibliography related to their project. That is, do some research on what has preceded what they are doing in a kind of domain or idiom specific way. So — doing a project on human-plant interaction? Seek out other projects in the canon of human-plant interaction projects that are inspiring and are helping ground the approach, thinking within a little universe of possibility. This kind of bibliographic work is a requirement in most other academic practices — you indicate the field through the work that has preceded or is adjacent, and then helps situate your work in a collegial way.

Oftentimes though we think our idea is the first of its kind and defines us as a truly unique little gem of creativity. In my experience, we are the accumulation of things before, alongside of, and adjacent to us yet aren’t always reminded that collaboration and coordination is also a useful creative operating system.

((I remember being called out by a student who claimed I had stolen their idea with a project when in fact that project preceded by a fair bit of time — like 7 years. Managing that without sending the student’s psyched into a nose dive was challenging. I think I would do better at that now 15 years later.))

Later in the day I got a tour of the Fowler School of Engineering facilities — which made me totally jealous. Awesome maker facilities with the things you’d imagine — 3D printers, laser cutters, robots, vinyl printing machines, embroidery and countertop spray booths, sewing machines, and so on.

One thing I noticed was that the students, as they introduced themselves, all had minors — secondary courses of study. I later found out that this was a requirement: every student has a major and a minor. And I was even more surprised (pleasantly) to hear students share that they were a Design Major and a Computer Science or Electrical Engineering Minor.

I mean..that, I have to say, was encouraging.

Why?

It indicates that Chapman values the potential of transdisciplinary learning and scholarship. The generalist — who is able to see across disciplinary silos — can see the horizon of possibility rather than the super narrow scope by which a solitary discipline sees, knows, and is in the world. The multiple epistemologies of the generalist or transdisciplinarian allows the adjacent possible to create new kinds of habitable worlds.

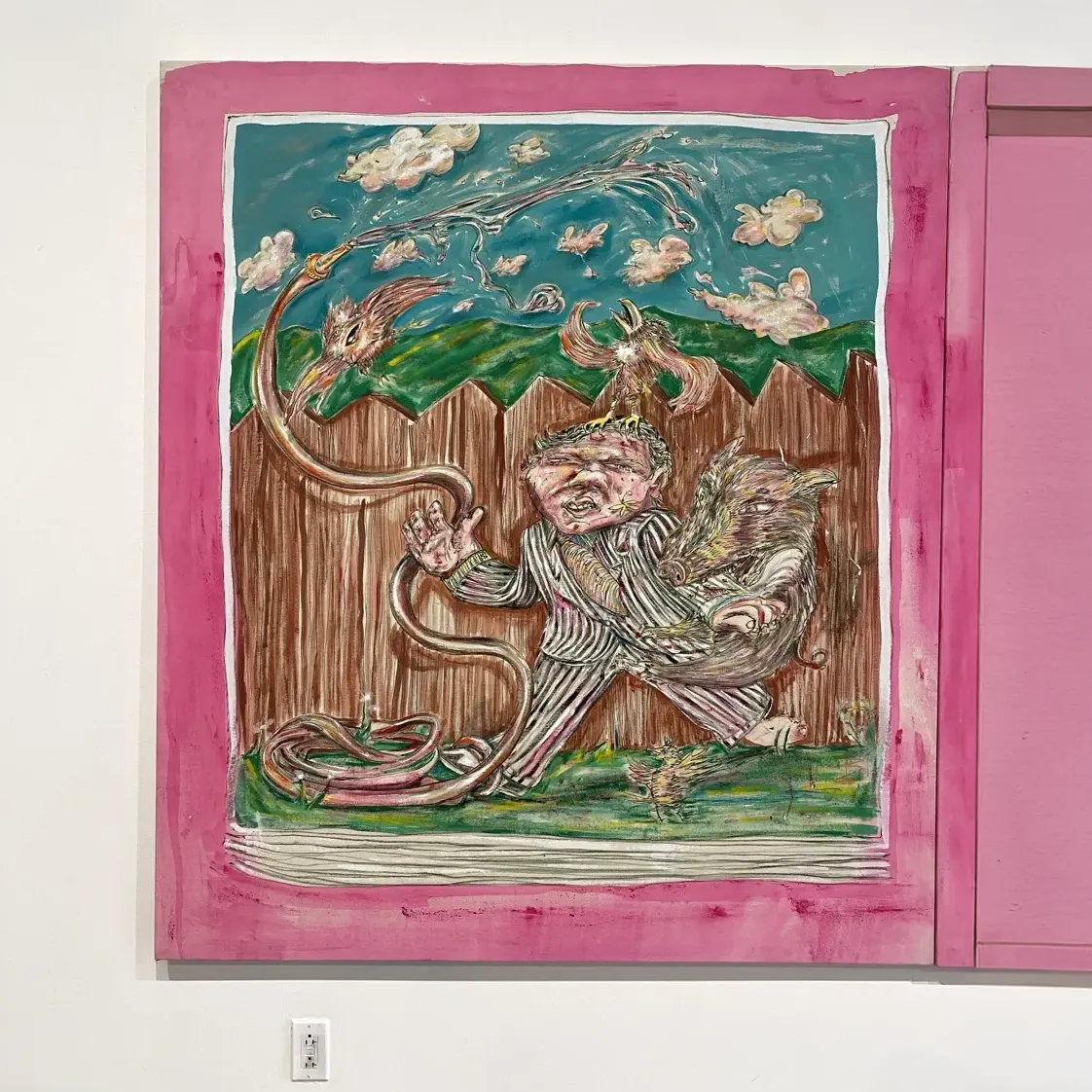

After a super pleasant dinner was the keynote lecture. In the weeks preceding the day I was waffling between presenting a slight variation on some existing material that was just sitting there ready to be presented, or some new quite formative material that was mostly based in some disjointed insights, reflections, and visual jokes. When I set aside time to work on this lecture, I literally had the old material sitting right next to the shell of new material on the big monitor. When I felt unsure about the new material, I just told myself that I could share the old material and be done with working on the whole thing. But then I’d turn to the new material and feel excited to continue developing it and trying it out, maybe a bit like a comedian trying new jokes.

In the end, I couldn’t resist sharing the new material and, from all indications, it was enthusiastically received. The Q&A could’ve gone on and on, but the room had to be cleared as the evening wore on. Oh, also — prizes for questions..I gave away NFL Merch as prizes for everyone who asked a question. That was fun. Like being a game show host.

Thanks to everyone at Champman University who made the day so awesome!