Title: ‘How to Rebuild an Imaginary Future’

Original URL: https://bruces.medium.com/how-to-rebuild-an-imaginary-future-2025-0b14e511e7b6

Created Date: 2025-03-17T18:59:25.359869-07:00

Title: How to Rebuild an Imaginary Future (2025) - Bruce Sterling - Medium

URL Source: https://bruces.medium.com/how-to-rebuild-an-imaginary-future-2025-0b14e511e7b6

Published Time: 2025-03-16T20:13:12.268Z

How to Rebuild an Imaginary Future

by Bruce SterlingThe “print” version of an extemporaneous speech given in Austin on March 12 at SXSW 2025.

**********************

Twenty years ago, here at South By Southwest, I was on a panel where the term “design fiction” was made public. Before Julian Bleecker invented and deployed that term, there were many things going on that resembled “design fiction.” But nobody knew “how to do design fiction.” The ideas and approaches were diffuse, they weren’t crystallised.

This current speech is taking place two decades later, in a era where “design fiction” has been normalized, and it’s practiced widely. “Design Fiction” is established, and is part of the worlds of design and futurism. This speech, “How to Rebuild an Imaginary Future,” is also about futurism, design, and design-fiction “diegetic prototypes.”

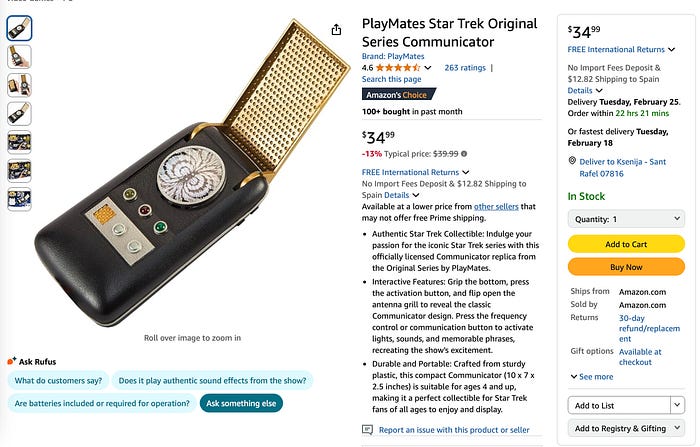

It’s about the issue of historical diegetic prototypes, such as this “Classic Star Trek Communicator” which I have in the glossy cardboard toy-box here at the podium.

Here you have a television science fiction prop from the Star Trek series in 1965. It was designed by the California special-FX maven Wah Ming Chang, who designed rather a lot of Hollywood props, but hit the jackpot with this one. The Star Trek Communicator has often been singled out as a famous “diegetic prototype” because it was an imaginary gadget with a large career outside the TV stage. It influenced engineers who were building portable cellphones, such as the Nokia flip-phone.

Nine years ago, at the Adafruit popular electronics company, they built a Star Trek Communicator that could make and take real cellphone calls. So it’s possible to actually “communicate” with Star Trek Communicators, more or less. They’ve also been packaged as functional “walkie-talkies.” In the past 60 years the Communicator had a long career as an “entertainment collectible.” It has been manufactured and re-issued several different times over the decades.

As you can see, when I demo this toy, it lights up and it makes the proper Star Trek squeaking noises. However, it does not geolocate me so that I can be transported by a beam ray to a passing starship in orbit. So it’s a somewhat realistic model from an old imaginary future. It can’t and won’t do every single imaginary feature of its original fantasy. That’s how it goes.

Also, it’s called “Classic Star Trek” because this futuristic device has become quite old. It dates back to the middle of the last century. It is older than most of the people in this room. It’s becoming antique futurism that properly belongs in a museum.

This handheld plastic toy is one part of a larger cultural problem of reviving old imaginary futures. So, how would you do that? Why? Clearly you would need some motivation in order to tackle that situation.

I am the art director of a technology art festival in Turin, Italy, which is called “Share Festival.” In our researches, we found a historical design-fiction that we want and need to rebuild for artistic and cultural reasons. And we are rebuilding it. It’s an artifact, an imaginary machine, from a science fiction story written 65 years ago by a science fiction writer in Turin: Primo Levi.

Primo Levi’s imaginary “Versificatore” is as old as a Star Trek Communicator. It is a cybernetic, desktop, mass-manufactured business machine that can write Italian poetry. The Versificatore works with prompts, very much like ChatGPT. So, Primo Levi’s historic “Versificatore” is a prophetic vision of Large Language Model Artificial Intelligence.

The Versificatore first appeared, in May 1960, as a character in a short drama piece that Levi published in a newspaper. Years later, that story was gathered into a collection of other futuristic gadget stories that Primo Levi also wrote, as part of a series of Levi’s science fiction satires and comedies.

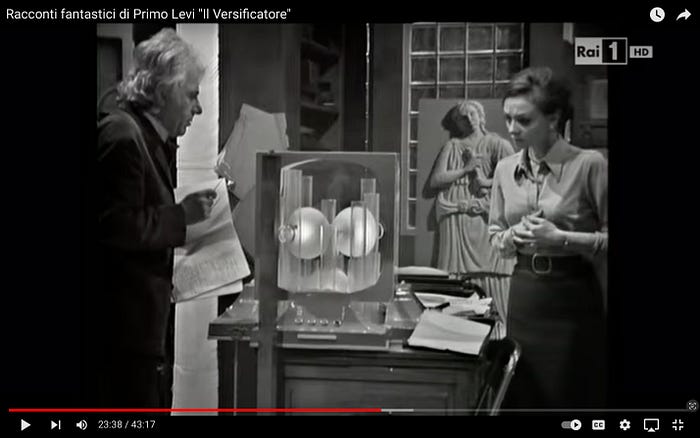

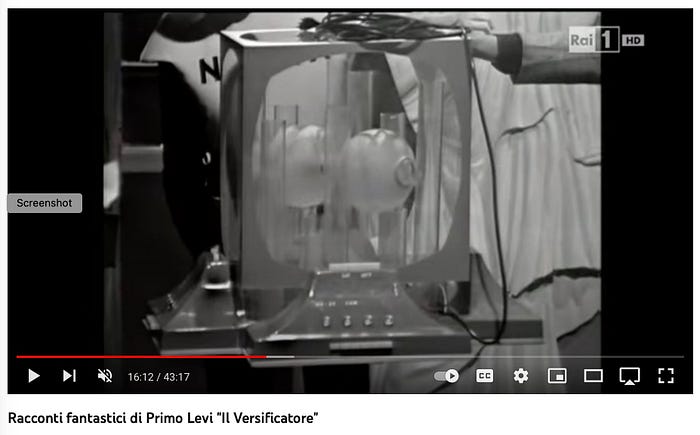

In 1971, the Versificatore became one episode of Italian TV series inspired by the Levi stories.

In these screenshots from the TV show, we can see an Italian poet, and a technology salesman, and a secretary interacting with their brand-new desktop poetry machine. The machine is a creative writer and is the center of the action in the drama. The humans react to this intelligent machine with varying attitudes of enthusiasm, amazement, commercial interest, dread, alarm and so on.

It’s quite amazing how well Levi understood the future human reactions to a novelty like an AI that can write human language. You can watch that show on YouTube right now, it’s quite engaging and funny. Of course it’s all in Italian, but who cares? As you watch the show, you can get Google’s Artificial Intelligence to translate the TV show from speech to subtitled text in real-time. It turns out, sixty year later, that Primo Levi was quite right about the prospect of machines with an astonishing command of human language. They’re very much here, and wreaking predictable havoc.

So, at Share Festival, thanks to a good friend, Riccardo Luna from “Wired Italia,” we became aware of Levi’s diegetic prophesy of modern AI. Since Primo Levi was from Turin, and we’re a festival from Turin, we immediately decided that we had to rebuild a Levi Versificatore and show that device to our public. We understand that the Versificatore has historic, artistic, cinematic, computational and literary significance. It should be a public source of civic pride.

In other words, we are motivated to rebuild an imaginary future. This is not a merely hypothetical project. It’s an actual artistic production project, and even a patriotic crusade. It’s a practical matter for us, where we have to raise funds, and find designers and crafts people, and find a venue for the display of our new artifact, and so on.

Since we’re a technical arts festival, and have been at it for sixteen years to date, we already do rather a lot of quite similar things.

So I’m going to describe some of these similar things, activities that are like this, and related to this, and are tangential to this, and maybe central to this. Let’s admit it: it’s a rather unusual thing to re-make an imaginary Italian Artificial Intelligence from the 1960s that works in public and speaks Italian poetry. But in this speech, I want to put that work into a larger context. It’s just one practical sample of a broader creative practice, which might be described as: deliberately turning culturally significant imaginary things into functional real-life things.

We are using modern capabilities to make things work, when it was once merely imagined that these things might somehow someday work.

This Versificatore project is a physical demonstration of the impressive prescience of a world-famous Turinese writer. Primo Levi made up some other different gadgets in his stories, but with this one, he hit the predictive jackpot.

We have means, motive and opportunity to rebuld this important object, for our public, which is the Turinese public, and for our client, who is MUFANT, the science fiction and fantasy museum in Turin. Turin has a museum of “fantascienza,” so naturally they’re interested in Turinese science fiction museum exhibits. Like this one.

So, with that given, what is the proper way to do this? We are confident that we can build a replica, but what are the best practices here? Who is else doing anything like this? Where can we get some help and good advice? How do we know if we’ve done a good job? What are we trying to prove with this project?

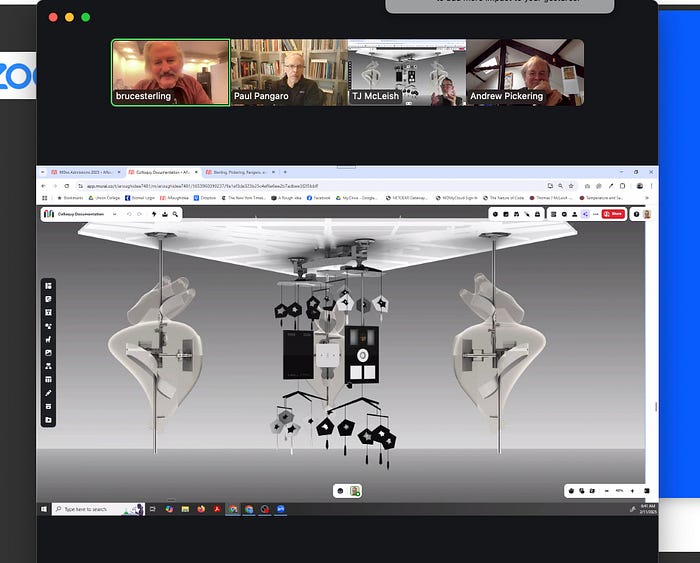

So let’s consider some other people — colleagues of ours, we should properly call them — who are also rebuilding lost objects of this historical period. Here I am conferring with a group of scholars from the “Colluquy Project,” which took place in 2018.

In 2018, these people joined forces and they successfully re-created a vanished electronic art installation from 1968. This was a prophetic British work from 1968, which existed in real life before our fictional Italian TV show in 1971. Many people call this artwork the world’s first work of interactive electronic art: Gordon Pask’s “Colluquy of Mobiles” from the famous “Cybernetic Serendipity” art show in London in 1968.

So, thanks to some determined effort by a network of designers, technicians, researchers, teachers and students, Pask’s artwork was successfully rebuilt 50 years later. That was well after the death of Dr. Pask, the original artist and inventor. And that restored machine works, it performs, it’s functional. It behaves today just like the first machine once behaved fifty years ago.

Somehow they managed to re-build it, on an academic budget, too. How did you do that? (I asked them eagerly). Well, (they cordially replied), we sent the graduate students into the archives. We measured the proportions with the Grasshopper architecture program. We substituted some materials, we got the right color scheme. We did trials with the motors and sensors until it we made it functional.

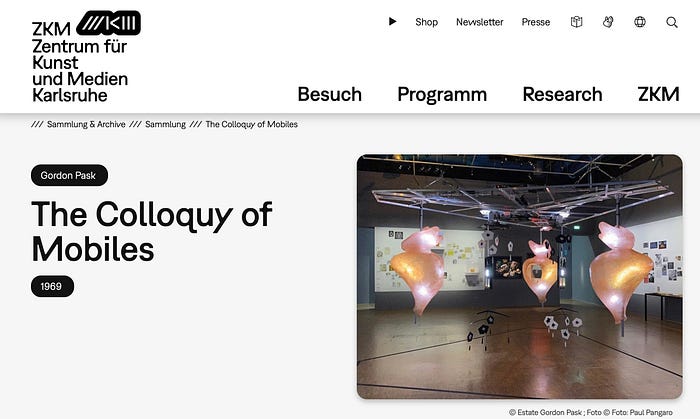

Then we shipped it off to a museum in Germany, the Center for Art and Media in Karlruhe, and there it is, a newly rebuilt art-machine as a historical display in a museum.

An impressive feat. This is an encouraging proof-of-concept for us at Share Festival. We probably won’t rebuild a historic Gordon Pask device by ourselves, but we would cheerfully put one on display at our festival in Turin. Antique, museum-quality electronic art, our public in Turin would be quite interested in that. We know that, because Italy already has one of the world’s oldest electronic art traditions, which dates back to the “Arte Programmata” movement of the 1950s.

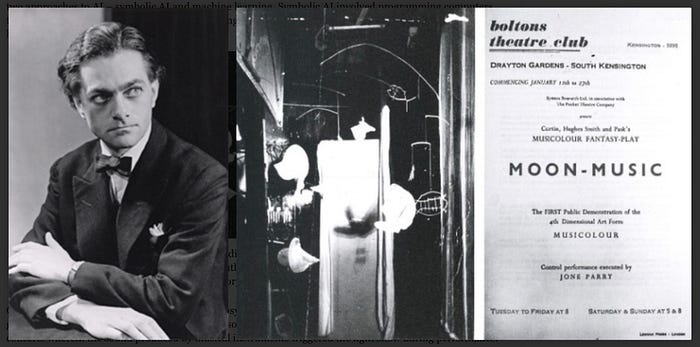

Nowadays, these competent scholars are rebuilding another Gordon Pask artwork. It’s called “Musicolour,” which was a quite different Gordon Pask art-machine invention, a prophetic, cybernetic, musical interactive device from 1953. Gordon Pask used to truck this Musicolour machine all over Britain and used it to put on musical shows in British music halls. The Musicolour was a commercial entertainment machine, but it was also a public demonstration of Gordon Pask’s academic theories of cybernetic interaction.

This can sound rather abstract, so maybe you should try to practically do this yourself. If you’re a hacker or maker, why settle for some art-director’s lecture, like mine? You might well have your own good, motivating reasons to revive and rebuild cybernetic demonstration devices from 1953. If that’s so, then after my presentation here, you should go get in touch with these scholars right away. I would urge you to do that.

https://www.pangaro.com/pask-pdfs.html

I’m happy to promote their historical revival activities. These scholars are in earnest. They’re not dilettantes and kidding about it. They’re experts and they can really do it.

So that’s some revived, historical machinery. What about the imaginary machinery? Well, here’s the Syd Mead Foundation. I’m also in touch with them recently, looking for insights.

Syd Mead was one of the first professional industrial designers who designed imaginary objects. These objects did not go into mass industrial production. Instead, they appeared as props in movies.

Many people give Syd Mead credit for creating the cinematic look-and-feel of cyberpunk movies, or even of worldwide cyberpunk subculture generally.

In the 1980s, Syd Mead was the top FX designer for Ridley Scott’s movie “Blade Runner.” Syd did rather a lot of movie work in his long career, and late in life, he established a foundation to sustain his artistic legacy.

So here are Syd’s heirs, the people who are running the Syd Mead Foundation in our present day. They are putting on public shows about Syd’s imaginary work. Not industrial products, but the props Syd Mead imagined and designed, which looked like industrial products. That was his profession: Syd Mead was a futuristic visionary with design skills.

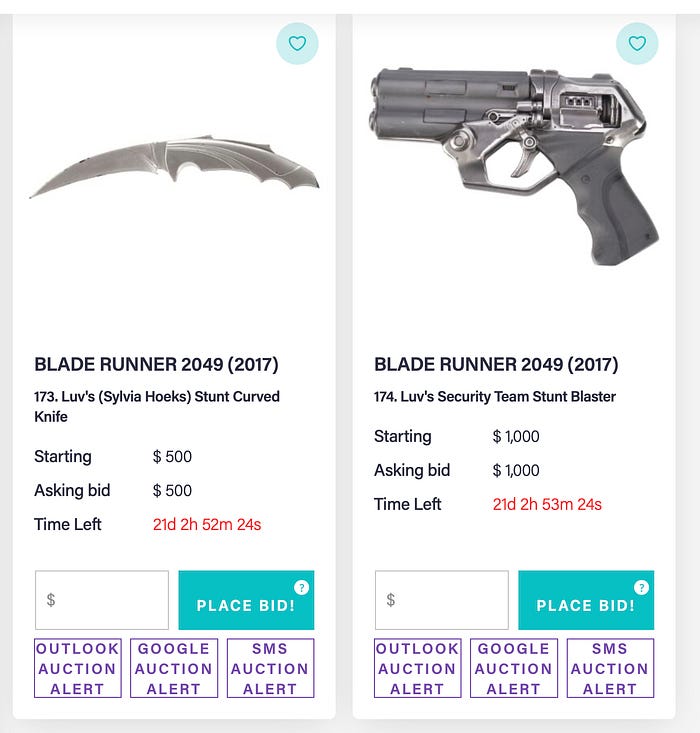

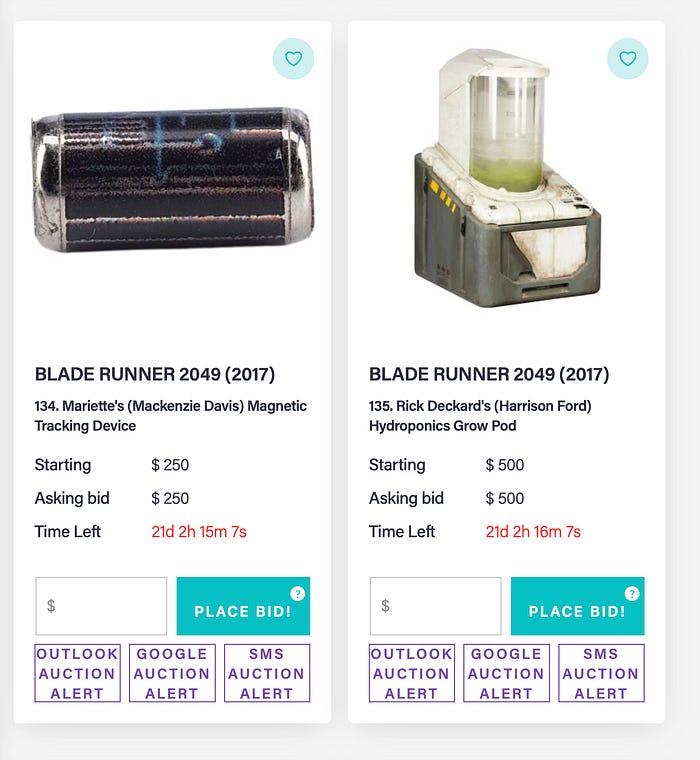

So do futuristic design visionaries have an artistic legacy? Do they have an existent art market, for instance? Well, check out these designer props from the set of the sequel to BLADE RUNNER, which is to say, the movie BLADE RUNNER 2049.

Syd did not design this movie in the franchise. He designed the earlier one from the 1980s. But this is definitely part of his legacy. Art collectors do buy these things. They buy them as “entertainment collectibles,” but they buy them and trade them. They’ll even buy the prop artifacts that look very eccentric and peculiar and are hard to explain to anybody.

Here’s a Syd Mead replica raygun, directly based on a Syd Mead design. This elite collectible was created in a limited edition of about 300. This device is more-or-less functional, because it performs the authentic Blade Runner blaster lights and noises. The “blaster” doesn’t actually blast anybody, which would be many kinds of illegal. But it’s an imaginary future object which is physically instantiated and behaves as if it is real.

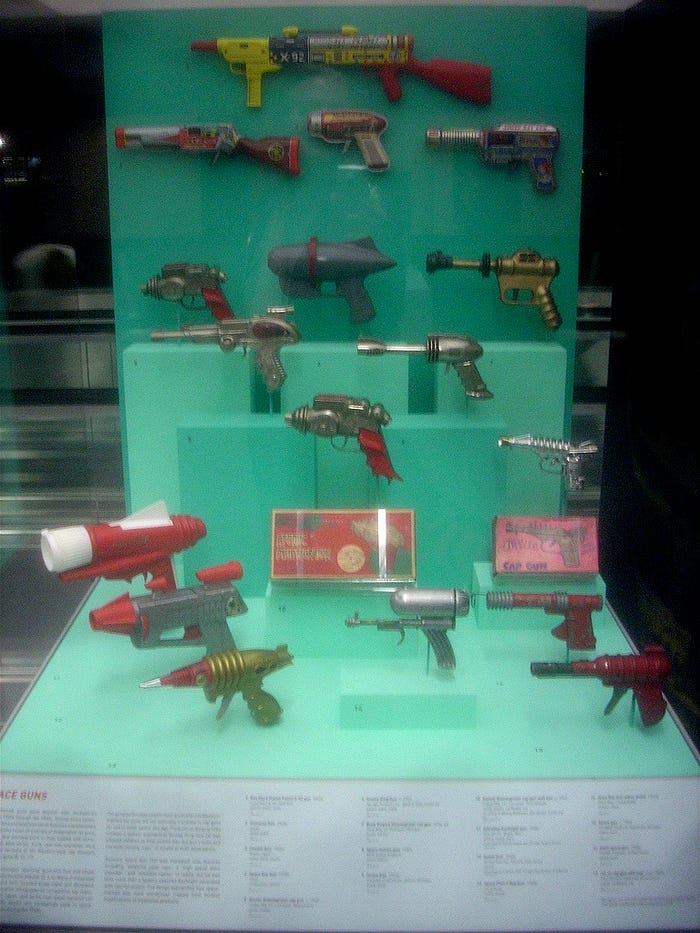

Here’s is a picture I took long ago in 2009. People were already diligently collecting historical rayguns and putting them on public display at that time. This is not like Syd Mead’s well-crafted limited edition raygun. These are stamped-metal factory kid toys held together with crude flaps of tin. So they’re not precious museum pieces, and yet they were treated like museum pieces. And they were old. They’re antique rayguns.

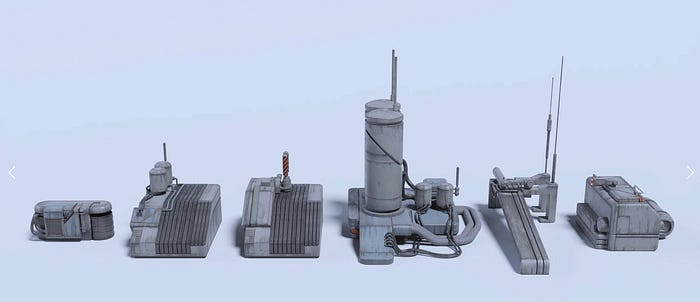

Here are some gamer special FX people who are creating and selling cyberpunk digital assets. You could go buy them right now, they’re for sale, forty percent off.

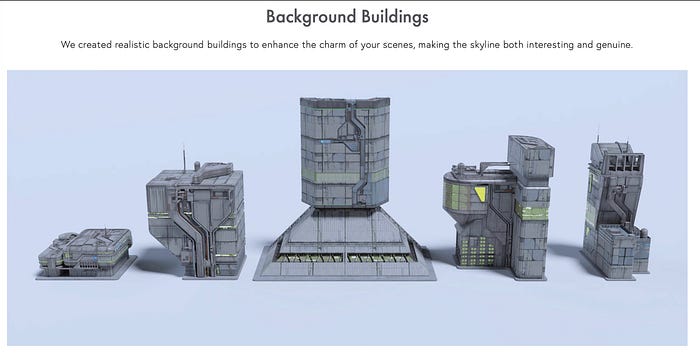

These gamer guys are not in Syd’s Hollywood movie business, but they are visual futurists in the gaming business. They are cultural heirs of Syd Mead. Syd Mead does indeed have a living cultural influence. It can be seen in this cyberpunk architecture from the game biz.

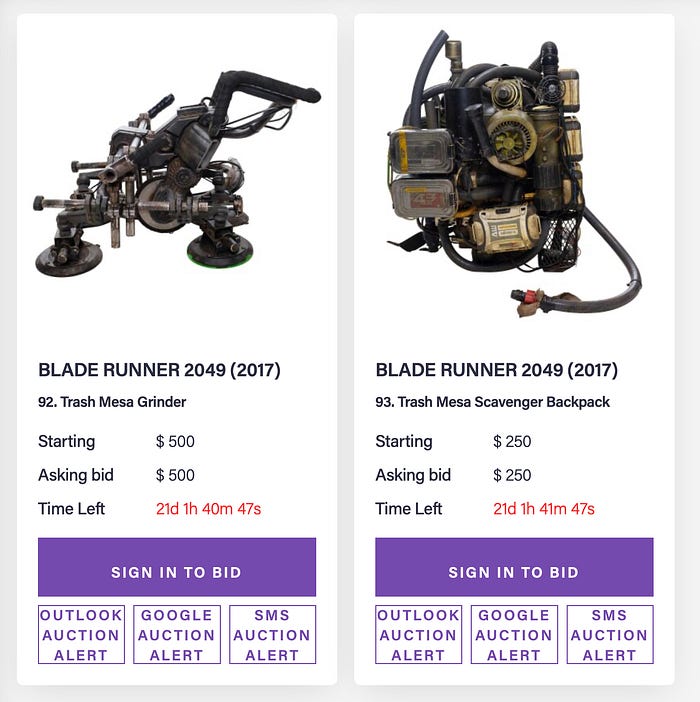

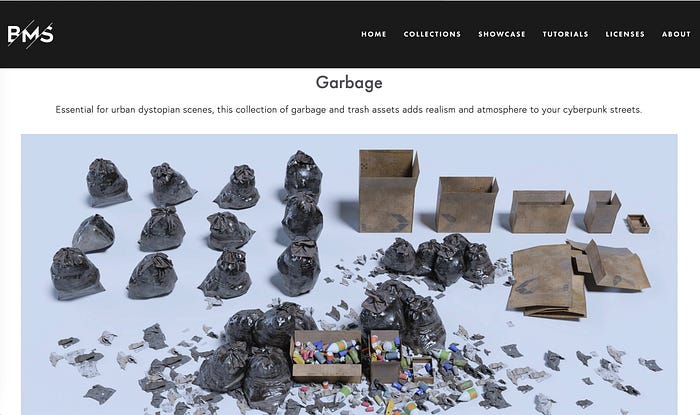

It’s also seen in things like this remarkable “cyberpunk garbage.” It’s interesting that this is not just random garbage, but garbage with distinctive cyberpunk visual characteristics.

The cardboard boxes have motor-oil stains. The black plastic garbage bags are especially thick, black and shiny. A visual futurist would know that even garbage looked different.

These are “cyberpunk greebles.” If you’re interested in the deeper issues of “rebuilding an imaginary future,” then greebles are a remarkable artistic problem, because greebles appear to be futuristic, but greebles have no function. Greebles don’t and can’t do anything at all. Greebles are mere visual suggestions, impressionistic sketches in a material form, that convey a dramatic visual atmosphere.

Once you know what greebles are, and you look at a special-FX movie, you can see greebles everywhere. Greebles are an interesting edge-case because they’re decorative and abstract. You can’t create a functional greeble, which used to be imaginary and became real. Greebles are imaginary imagery. They’re like croutons in a soup. They’re just there to add their tasty crunchiness.

So: you can have greebles, the props without the futuristic functionality.

You can also have the futuristic functionality without the props.

That sounds plenty weird, but in real-world technological development, this happens. I think this happens much more often than people understand; some new technology appears, but it’s not interpreted as a real-world fulfillment of some distant speculation from the past. It’s some speculative dream come true, but the dream has been forgotten.

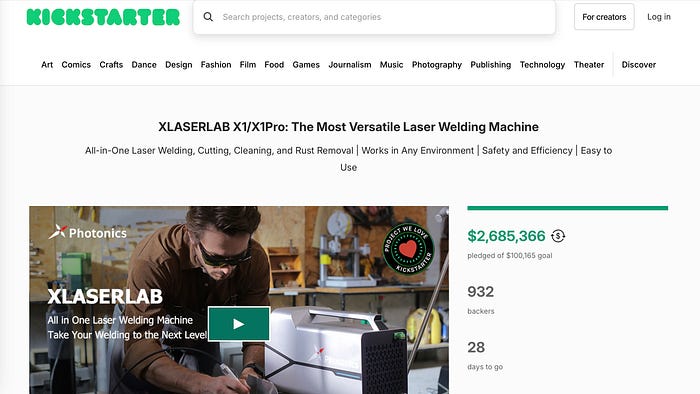

For instance, here are some contemporary crafting people with a Kickstarter program. They have built a functional raygun. However, they call this device a “‘laser welder.” It works great as a welder of metal. The supporters are really excited about it.

But it’s a gun-shaped ray device that works. It will functionally blast damaging rays right across the room, as you can see on the screenshot here.

Here’s a welding fan who owns this device, and is reviewing the laser gun on YouTube. Here he realizes that his new gun will blast your face off. It’s created and sold as a welder, but it’s also a functional blaster device. If you place this instrument inside a Syd Mead model raygun and pull the trigger, that contraption will blast somebody. It really will.

It is not a practical weapon, in terms of any real-world military usage. That’s because ray guns do not work well in battlefield smoke and dust. If you blast somebody with a ray gun, smoke comes off the target, and then the ray scatters in that smoke. Also, any normal fog, rain and clouds will quickly hamper military rayguns. However, this device is a ray gun, by any reasonable ray-gun definition. Ray guns are quite an old, historic idea, and they date back at least to 1897.

The girlfriend of Buck Rogers had a raygun a hundred years ago.

Here she is, Wilma Deering, the romantic-interest and loyal sidekick of Buck Rogers, as a hundred year old sci-fi paper doll. A paper doll is pretty much the “minimum viable product” among the class of entertainment collectibles. This particular Wilma Deering is not original. Instead, she is a “rebuilt imaginary future” paper doll. She was not made from any hundred year old newspaper comics page. She was digitally scanned and then laser-printed on modern printer paper. This modern activity re-created this new Wilma Deering paper doll.

This rebuilt Wilma Deering looks almost identical to the century-old paper doll, except, since the technology has radically shifted in a hundred years, Wilma Deering is digital and can be printed out easily in any size.

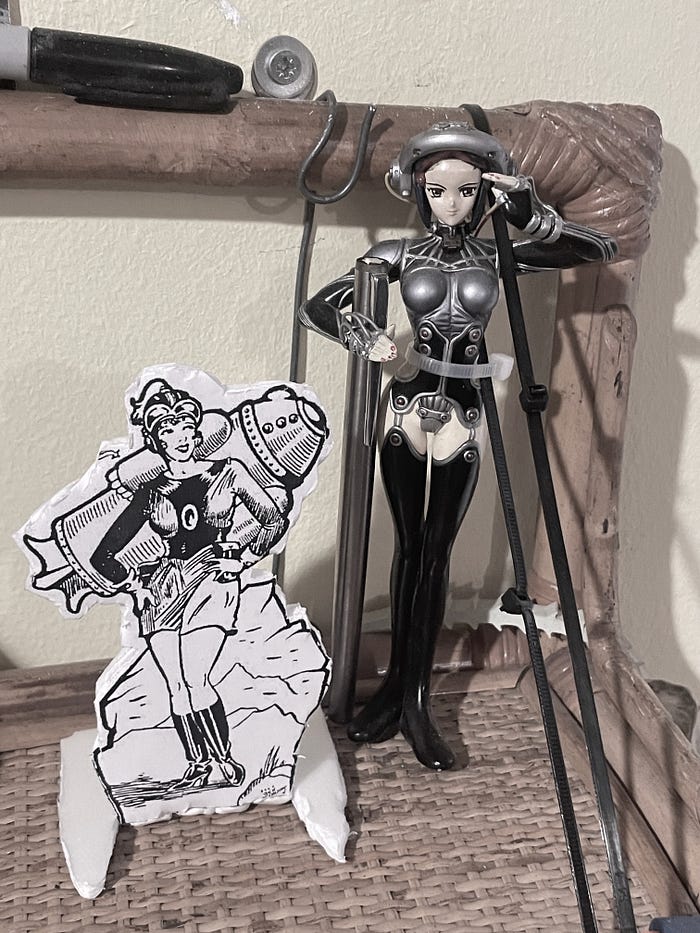

Here’s comic-strip paper doll Wilma Deering of the 1920s, standing next to one of her many planetary descendants, Motoko Kusanagi from the anime cartoon “Ghost in the Shell” in the 1980s. If you’re an art historian, you would immediately see that these two figurines have plenty in common. Strange goggled helmets, peculiar and exotic hardware, pretty girls showing a lot of leg in a standard actress-style. Obviously they’re from the same cultural tradition.

Do they belong in a museum? One is already a hundred years old, but some day, the other one will also be a hundred years old. History works that way, that can’t be helped.

When, exactly, do they become two futuristic antiques? What is the nature of that historical process? When “Ghost in the Shell” is a hundred years old, how do you explain “Ghost in the Shell” to people? How do you explain “Wilma Deering” now?

This paper doll and this plastic action figure are “entertainment collectibles.” The collectibles business is getting pretty big. It even has its own distinct product categories. Most of them are toys, but some are furniture. In terms of design and manufacturing, this is a peculiar world here. There seem to be major consumer categories missing, like, say food, fashion, and fragrances.

Or cars. It’s not new for design prototypes to turn into real things. Here’s a picture I took recently in Turin: it’s a FIAT concept car from the 1954, the year I was born.

First the Turinese made the cute little wooden model, and painted it. It’s the product of a car company, but it’s quite similar to a collectible movie prop, and it’s offered for sale now as an antique model car. Then they built the concept car seen in the photo there, a concept-car which functioned, and has vanished. That real car once had a real, functional motor, wheels, brakes, and a driver. It was a car that existed to publicly boast about FIAT and demonstrate FIAT’s futuristic manufacturing skills. That car was never a mass-market commercial FIAT car. It was a futuristic publicity FIAT car that was built to get public attention. It was a publicity stunt, like a self-driving Tesla truck, or a Waymo taxi. That happens all the time.

I would even say that my Italian audience in Turin is keen on this practice. This is their great-great-grandparents doing this. It’s not new. It’s a historical activity.

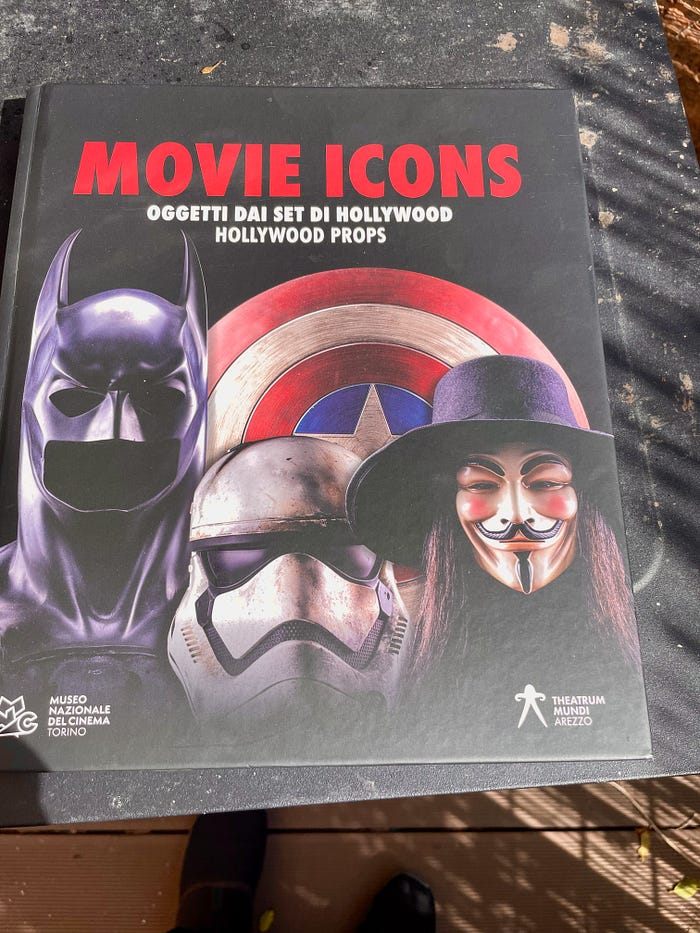

In Turin there is a National Cinema Museum, a state supported institution, and quite large. Here they are, last year, putting movie props on display inside their national museum.

Here’s the book of the museum show. The National Cinema Museum often prints these scholarly works on cinema history, so of course I bought the book after I saw that show.

It’s got a raygun on display in the museum. Of course.

A Men in Black neuralyzer, it’s a sci-fi gadget that flashes, and destroys your memory.

A headmounted display from the movie Ready Player One, the Spielberg movie made up by Ernest Cline, an Austin guy. Austin cultural imperialism, that’s always nice to see in Torino.

Some people might object that fragile movie props are not proper museum quality objects. Commonly, the objects preserved in museums are already quite old, and they’re meant to last for generations. Movie props are ephemeral by nature, they won’t last long, and were not built to last long. I would agree: that’s a serious restoration and preservation issue.

But it’s not a new issue. There are quite a few theater prop museums in the world that are even older than cinema prop museums.

They protect theater costumes and theater posters. Fabric and paper, mostly. You might have, for instance, a costume worn on stage by the famous opera singer Jenny Lind. But it’s not enough just to store, or even repair and restore, that fragile, decaying dress. You have to explain who Jenny Lind was, and why she mattered. You might even have to explain opera.

The Italians have a museum economy. Turin has a National Museum of Cinema. It has a museum of ancient Egypt that is two hundred years old. Turin has a museum of cars, and a museum of fountain pens, and a museum of ice cream.

Why so many museums in Turin? Well, these museums are not profit centers in themselves. They function as tourist attractions. The city supports the museums so that the armies of tourists will have something to do. Also, Italy is an old region of the world, with a lot of heritage. All human societies are getting older. When you have a plethora of heritage existent on-the-ground, it becomes necessary to invent ways to deal with that.

So, we’re Turinese at Share Festival, and we’re applying for state money to rebuild an imaginary future. We are not making Versificatore entertainment collectibles to sell in a prop collector market. We might possibly do that, because we do understand what’s going on there, but that’s not who we are: we’re a culture festival.

Our Turinese efforts might be understood as part of this larger Italian effort, which is “Industrial Heritage Tourism.”

We’re building a replica of an industrial heritage machine, which happens to be an imaginary machine. Our unique value proposal is that we intend to re-build an imaginary machine from 60 years ago that can work in the present day. We’re a state-supported art-and-technology culture festival. We’re arguing that our culture-ministry sponsors should fund this effort for cultural reasons. Turin needs and can use a Versificatore because a Versificatore is so Turinese.

But a Versificatore can’t merely work as some standard commercial manufactured object, like an old car, or an old typewriter. A Versificatore is old, but it has no commercial purpose. It’s not a commodity and it never will be. Instead, it somehow has to work as a revealed prophecy. It has to work as an object of civic pride. It’s an artifact of the visionary spirit of the city of Turin.

Once it’s inside a museum, it becomes monumental; then you can witness it, maybe touch it. It exists as a revelation.

How does this situation make sense?

Italians have museum preservation theory.

Why is one old object a precious prize in the museum, and another thing just as old, is never in the museum?

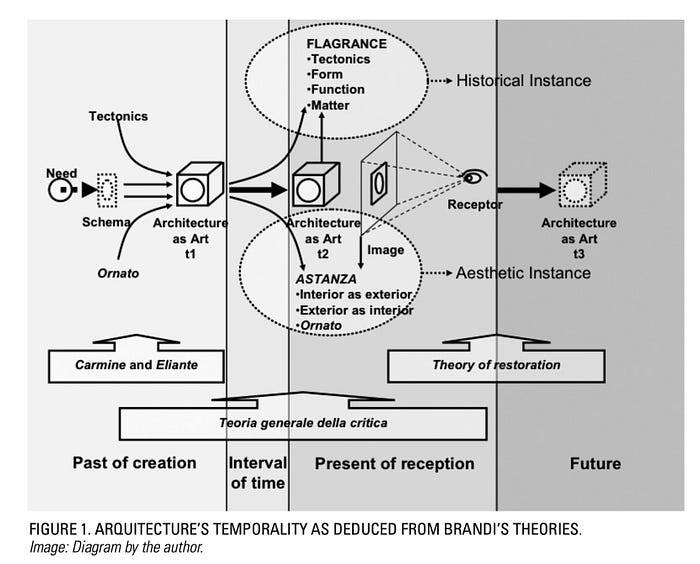

It’s got a lot to do with this impressive scholarly diagram here, which is mostly about metaphysics and semiotics.

I don’t have to believe diagrams like this, but as an art director in Turin, it’s incumbent on me to engage with this. I’m not demanding that you here in the audience in Austin, Texas should do that right now. However, I do that, and I find it edifying.

We want to achieve a worthy cultural effect through rebuilding an imaginary future. It’s not some mere gadget or collectible toy, it needs to be an intervention that conveys an artistic frisson and a cultural message.

So how do you do that? Well, you can’t just roll it out on a truck and drop it on some museum floor. In order for it to work in an Italian museum context, you have to curate it within an Italian museum context.

This is actually the hard part of our project here. It is, I think, the hard part of any such project anywhere in the world.

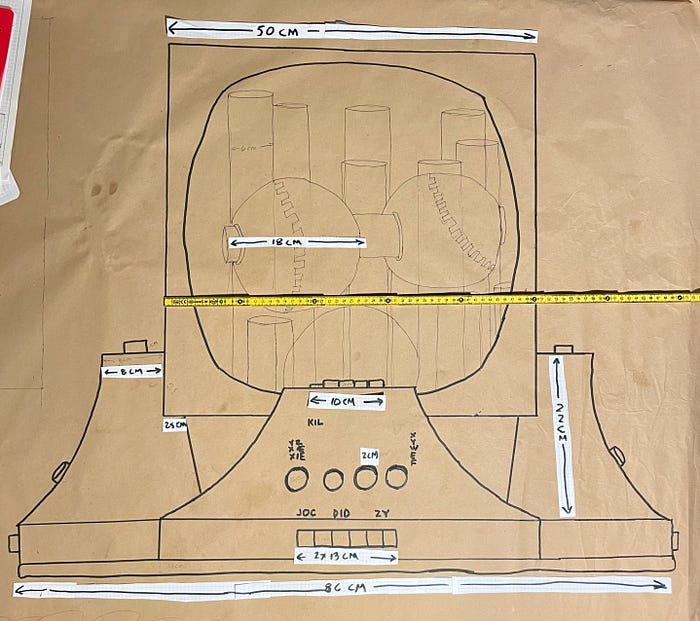

The how-to issue is a problem, but as an art director, I’m not much worried about the problem of physically re-building a Versificatore. A Versificatore was already built by Italian TV studio technicians back in 1971. It was made cheap-and-fast out of standard stage-prop plywood, plastic and glass tubes. We believe we can make another pretty-good one out of vacuum-formed plastic, and LED lighting. And also Arduino control boards, because Massimo Banzi, who is the capo of the Arduino electronics company, is kind to Share Festival and he smiles on our efforts.

We did some research. We have some knowledgeable allies. We know other people who have successfully built, or re-built, similar artworks. We already built three or four practice versions, as simple design mockups. So it’s still a work in progress, but it seems likely that we can get that work done.

We plan to build one in September that we can show to the public in the city of Turin. This new device will look and act like very much like the original Versificatore on the 1971 TV show, which no longer exists. It will be an accurate replica prop.

It’s an experiment on our part at Share Festival, but as a construction project, it’s within our reach. The more serious problem is in this theoretical diagram here. Which is: not “how” to rebuild it, but for whom, to what purpose? Why does anybody care? What does it signify? That’s the larger issue.

Suppose that I build a Versificatore prop replica, and I roll it onto the SouthBy trade-show floor out the door over there. It might attract a few curious passing glances, among the many other booths and many other odd ambitious projects. But nobody would catch on! It would lack meaning.

We don’t much need another sci-fi prop. The world has plenty, for decades on end. We need an object of cultural heritage with a sustained existence and a guaranteed integrity. It needs to be a public tribute worthy of this important world-class writer Primo Levi.

Primo Levi has often appeared in museums. Even his typewriters, which were made by Olivetti, have appeared in museums.

If we can re-build a Versificatore, and the public appreciates that effort of ours, that’s swell and I’ll be happy. But this speech is not about one regional gadget dreamed up by a world-famous regional writer. Our imaginary-future rebuilding project might also open up new conceptual room, new possibilities, for other people elsewhere, in these other, related areas of industrial heritage, art tourism and museum economics. It’s a local problem with global implications.

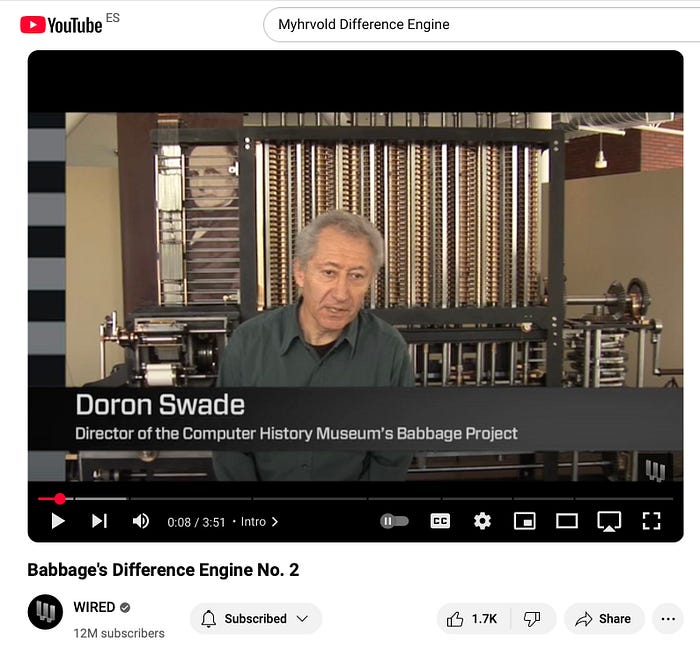

Here’s one example of this being done on the grand scale. This is Doron Swade of the London Science Museum, with a Charles Babbage computing machine from the 1830s, as rebuilt in the 1990s. Doron Swade met Nathan Myhrvold, who is a Microsoft millionaire American rich patron with some visionary interests. Nathan Myrhvold knew about this imaginary steampunk future for computing, which had never existed.

So the art patron, the American Nathan Myhrvold, and the British museum technician Doron Swade, formed an international partnership. Doron Swade has the documents in the archives. He tells Myhrvold he thinks he can really build one, that works. Myrhvold says: then build two, you keep one and I’ll keep one. They shake hands on the deal. They don’t even sign a contract. This historical re-creation project takes about ten years and eleven million dollars. They build, or re-build, two Difference Engines. And those Engines work.

They don’t work like Difference Engines were supposed to work, in the original circumstances of Charles Babbage. These machines of the 1990s have no practical computing applications. They don’t generate any revenue as computers, or have any military applications for the British Navy.

Instead, they work like successful museum attractions and collectible artworks. Nathan Myhrvold owns the one in his own living room. If he were to sell it tomorrow, I’m confident it would bring a whole lot more than just ten million dollars. It’s an artwork that appreciates in cultural value. It was by no means a crazy thing to do. It turned out to be a quite successful, farsighted thing to do.

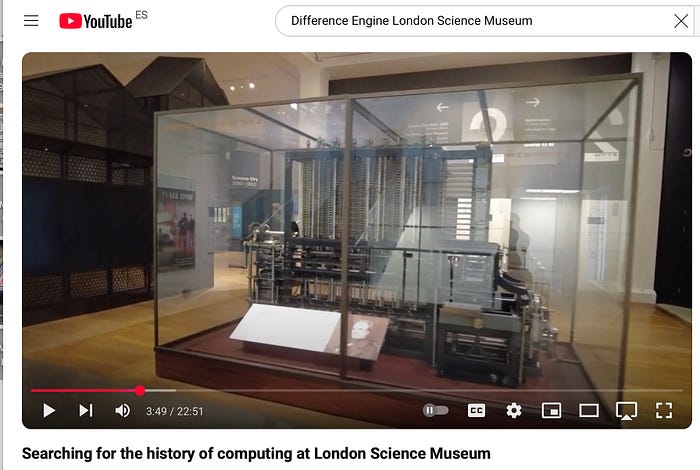

The rebuilt Difference Engine brings in a lot of foot traffic to the London Science Museum. Here it is nowadays, on show in the big glass vitrine. Charles Babbage, the inventor, is famous today. Lady Ada Lovelace, the publicist, is also famous. This Difference Engine replica project had a big cultural effect, worldwide. It’s the premiere, top-end example of what I’ve been discussing here.

That was an eccentric yet impressive feat, but that was in 1991, a long time ago. That Difference Engine is 34 years old now. A computer that old would likely belong in a museum anyhow.

I would close my presentation by arguing that the methods of how to do this are changing radically. It’s easier to do this tomorrow than it is to do this today.

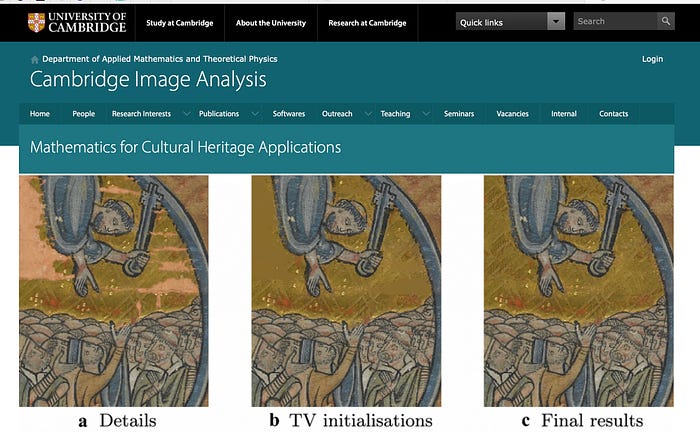

People have been trying to repair medieval art, by hand, for literally a thousand years. You have to find some well-trained expert. He has to understand the pigments and the substrate. He labors until he goes blind. He can fix maybe ten, twenty of them in his human career. Or, you can haul in the stochastic-parrot AI here, and have it stare at the specimen on the micrometer scale, finer than any human eye can see. It can use, for instance, spectrogrammatic chemical analysis of the pigments and parchment substrate.

Bingo, it does its thing. Instead of cheap and fast generated art, it’s cheap and fast generated art-restoration.

Of course, that’s problematic, and we know it. But suppose that you have a flood (because of climate crisis) and your medieval library drowns. Can you restore a thousand damaged books? By the human hand? How? How do you rebuild your lost past?

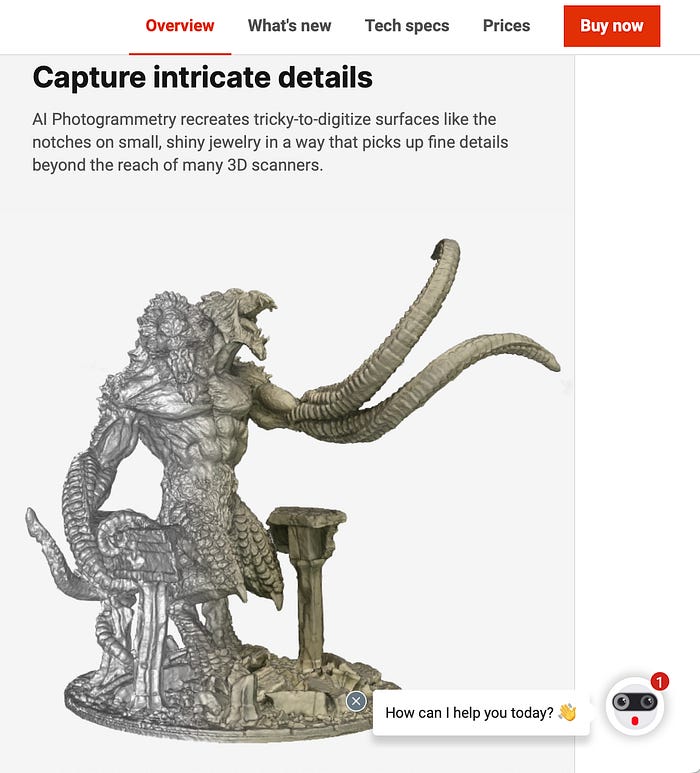

Photogrammetry derives the shapes and proportions of objects from old movies and old photographs. It’s an app on a mobile! It costs ninety-nine cents!

Okay, it doesn’t work very well. But it’s alarming that it works at all.

If you can have AI fake photos of things, then you can derive fake 3D blueprints of things. Cheap 3D fine detail.

There’s such a thing as computer heritage gaming. It’s rather squalid, frankly. You just put a Chinese box around the old game and sell it as shovelware. For the price of the plastic, basically.

This is fancy software from 30, 40 years ago. It’s also the fate of our own software in another 30, 40 years, because this is the established way that electronics heritage gets treated. The heritage is squalid like this, because we ourselves are squalid like this, but it doesn’t have to be like this.

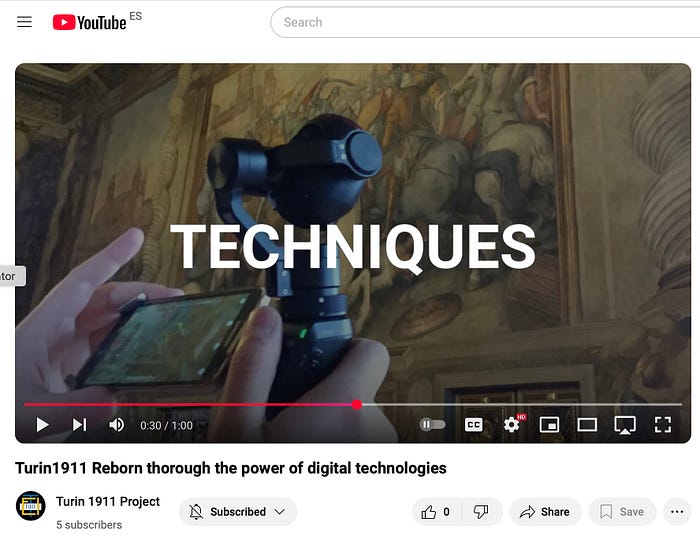

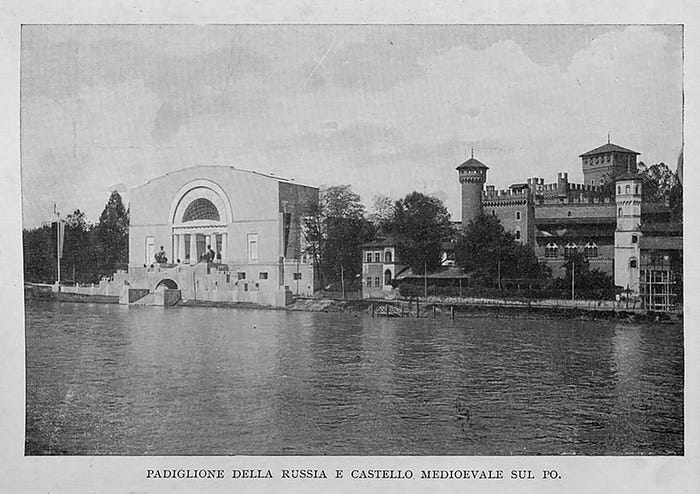

We’re a festival from Turin. These are academics from the Turin Polytechnic, and UC San Diego, who are scanning an entire world’s fair festival in Turin from the year 1911. Not some Primo Levi gadget like we want to re-build, but a city-sized world’s fair.

They want to prove that this can be done: a digital, virtual restoration project of long-vanished fantasy buildings on a grand, urban scale. They go into the archives. They scan all the documentation. They find the old photographs, the old silent films. They send drones out to map the urban geography. They use architectural software to model the long-lost buildings. They re-perform the old fairground music.

This is the world’s first fake medieval castle building, built in Turin in the 1880s. That historical replica is still proudly standing there today, and it is being rebuilt again, now, today. The huge building next to it was created by Czarist Russians. Not only is that fairground building long gone, the whole country’s long gone.

“The Palace of Industrial Manufacturing.” This event was similar to a SXSW trade show. Technicians in Italy were inside the pop-up fantasy palace there showing off their best high-tech machinery in 1911. That palace been vaporized for 114 years. It will never come back. But that Manufacturing Palace was industrial tourism. It looked incredible. You could print out a diorama of it, maybe even animate it.

It’s astounding that Turin in 1911 would pay to build a “Palace of Industrial Manufacturing,” put seven million people through that building and then throw it away. But that approach is very like them: palaces and factories. They’re all about that, in Turin. The “Palace of Industrial Manufacturing” may be the most Turinese building ever, in the way that the eloquent, poetic, mechanical Versificatore is somehow the world’s most Turinese machine.

Okay, this effort can be just an amusing toy — like a futuristic Star Trek toy from 1966, even older than our Versificatore, available to point click and ship. I clicked it and I own one, as you can see, it’s in my hand as I’m speaking.

I don’t mind those toys at all, I even enjoy them, but the technological underpinnings for doing this are changing fast.

Image-classification. Object-detection. Pose-estimation. Instance-segmentation. Ultralytic rotated-object-detection. Machine-learning computer-vision deep-learning.

It could become slop manufacturing, another tidal wave of careless “crapjects.” Or, it might become illuminating, it the sense of changing our basic relationships to objects and products and their potentials.

“Slop engineering” will be slop, in the way that “vibe coding” is slop, or, for that matter, generated Italian poetry is slop. I wouldn’t trust it for mission-critical applications, but there may be specialized applications — like rebuilding long-lost or scarcely-possible objects — where slop engineering might be sensible. It might enable the existence of things that would never otherwise be feasible.

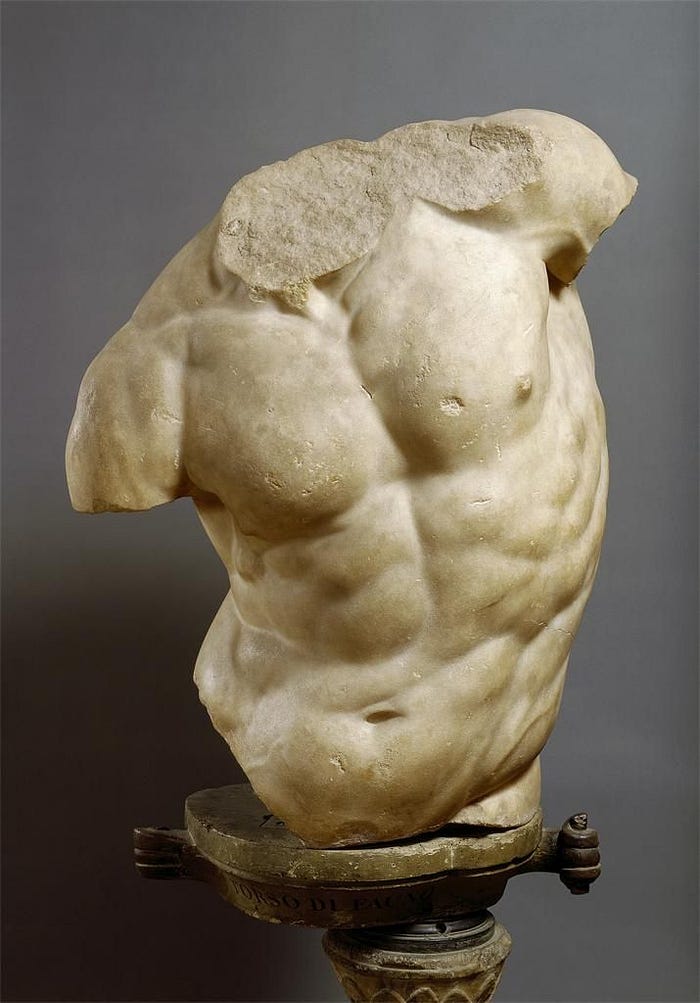

Consider this useless object in Italy in the Renaissance. People had thought for a thousand years that the dirty wreckage of ancient Rome was ugly, broken junk.

People would dig up a broken classical statue like this one, be annoyed by it, and promptly destroy it even more. Sometimes they would restore a new head on a damaged classical statue, put new arms on it. They wanted it to work again as a proper statue — to look nice, to look like art. Sensibly, they thought you can’t just drop a piece of dead, broken junk in your living room, and expect admiration and appreciation.

In the Renaissance, cultural attitudes toward materiality changed, and the worn-out old trash became the precious classical heirlooms. That was cultural restoration, and it was not about the old stone, which remained as it had been for a long time; it was mostly a renewal of the culture and its attitudes toward objects.

The “New Heritage.” Everybody knows that heritage can only be old things that are precious and yet slowly dwindling away. The past simply has to decay. It has to go away and get lost and forgotten. You can’t go back to the past and make any new fresh past that isn’t old.

In a way that is very true — it’s starkly true like entropy and the Second Law of Thermodynamics are true. But if you study the past of the past, and understand why people would want to be proud of their heritage — instead of just stoically remarking, “it’s gone forever, so what?” — then you start finding a lot of novelists.

Specifically, Walter Scott, Victor Hugo, Prosper Merimee, Camillo Boito, Albert Robida and the American in the group, Washington Irving. These creative writers wanted to make the past come alive, not literally, but literarily, in works of fiction. These historical authors joined ambitious, political state-supported projects that attempted to revive dead or declining buildings. Sometimes they revived whole urban districts.

It was a folklore project. It was about meaning and feeling and a significance which could outlast the generations. They wanted people to feel the past in their living bones, before those bones, too, were dry. It was a romantic and passionate attitude toward the past, and not the analytical attitude of an archeologist, although archeologist also have museums. They do a lot of conjectural historical restoration labor — the paleo-artist restored flesh on the long-dry dinosaur bones.

This project that I’ve been talking about, it’s a design fiction project. I said twenty years ago that design fiction is a form of design, and it’s not a genre of fiction. Historically, design trends come and go. This time, it might be the fiction that matters more here. This Versificatore device, it’s not a manufactured work of industrial design from 1960. It looks like one, but it’s a work of fiction from 1960. That’s why it matters today and tomorrow.

I don’t want to end here by praising novelists, because that’s very corny for a novelist to do. But my speech here has an outstanding verbal problem, which is: the world lacks a proper term-of-art for “an artifact from a rebuilt imaginary future.”

If you perform this process, and you create a thing, what kind of thing is it? What do you call such a thing? It’s a design-fiction of sorts, but what kind?

I’ll recite some possible neologisms here. The Antique Prototype. The Modernized Re-Creation. The Functional Replica. The Very Special Effect. The Futurized Skeuomorph. The Uchronic Artifact. The Retro-Futurist Anachronism. I’m circling around the proper term here. We don’t have it yet.

These ideas are diffuse, not yet crystallized.

I’ll offer one last word. That word is “Realization.” You should rebuild an imaginary future, not as a clever stunt or a stage-trick, but for the sake of the realization. You have this old imaginary thing which was fantastic, or even sarcastic and satirical. Maybe absurd, surreal and bordering on zany, but then, the technological platforms change. Then it becomes possible to “realize” that dream of some past visionary figure. It becomes a public tribute to him and his lost world.

Also, you and your colleagues realize something by the act of realizing it. You arrange the situation so that the public can realize as well. It becomes more than a mere toy, or a pricey collectible, or an archaic artifact under glass in a museum.

It’s a living and persistent insight into how we are, and also what, and where, and why, and who, and when we are. When you have all those things aligned, you don’t have mere passing gadgets of circuits and plastic, you have a culture. You have a civilization.

So, thank you for your attention.

BruceSterling

A nearly verbatim Xerox of Bruce Sterling's 2025 SxSW talk titled 'How to Rebuild an Imaginary Future'. I duped it because I trust the foundation players like Medium to keep the original. I remember how it took years to get an audio copy of the Design Fiction panel from SxSW back in 2010. I'm not sure if I'll keep this here, but I wanted to have a copy of it in the stacks. I'm not sure if I'll keep this here, but I wanted to have a copy of it in the stacks.

](

](