I used to ride mountain bikes.

I was never very good at it.

Mostly because I never felt at home with the culture of it.

But mostly because I didn’t want to break any bones.

The best rule-of-thumb I learned to avoid breaking any bones was this —

Never look at the spot where you don’t want to end up.

Stop looking at the danger.

Stop looking at the bone breaker.

Stop looking at where you don’t want to go.

Look at where you want to go.

Same goes for worldbuilding.

Don’t imagine the world you don’t want to inhabit.

Imagine the world you’d want your kids to live in.

I say that to say this again: it’s time to imagine harder.

My rejoiner to the oft-quoted and confusingly attributed phrase:

“It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

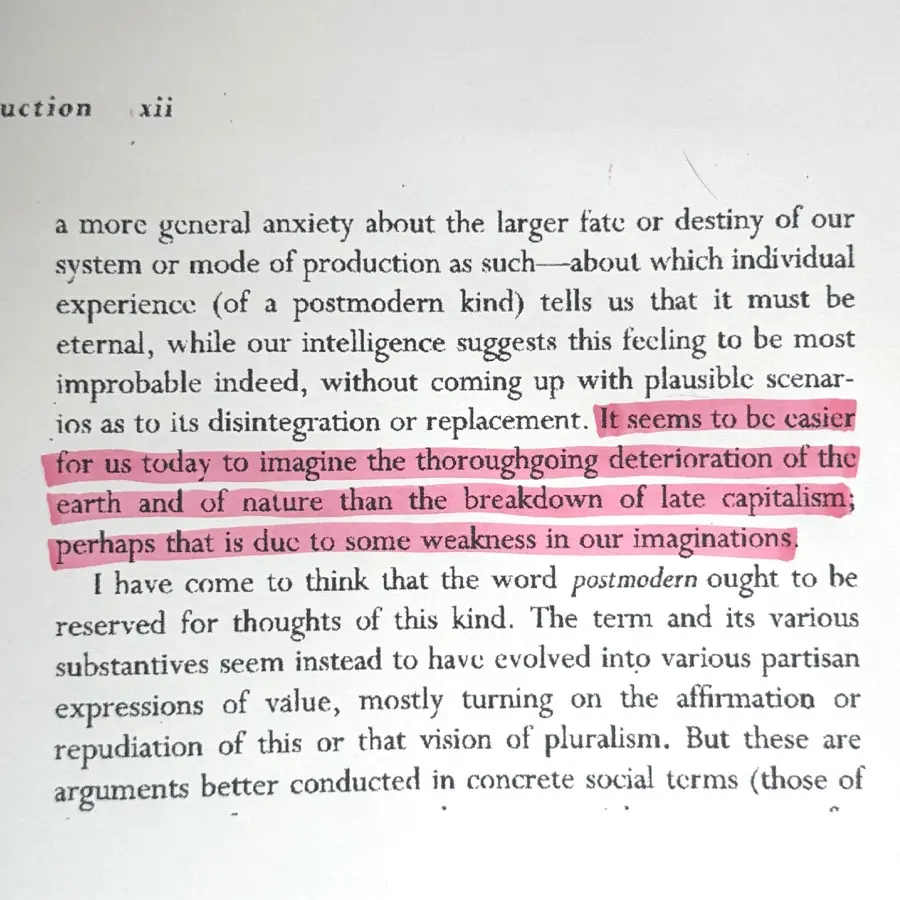

The phrase - near as I can tell - is an evolution of a passage in Frederic Jameson’s “The Seeds of Time” (1996) where he writes:

It seems to be easier for us today to imagine the thoroughgoing deterioration of the earth and of nature than the breakdown of late capitalism; perhaps that is due to some weakness in our imaginations.

It’s a phrase that has been used in various forms by various people, including the late Mark Fisher, who wrote about it in his book “Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?” It’s the chapter title to the first chapter of the book!

The idea that we can’t dream of a world without capitalism is a powerful one.

It’s effectively saying that it’s easier to give up and pull a cork on a chilled Chablis and chill.

Which is another way of saying that we have forgotten how to dream, the result of which is that we are effectively living in someone else’s dream.

The dreamer who dreams so effectively that they make it so that you want to follow them and live within their dream?

That may be a definition of the charismatic.

That person with a dream that one feels compelled to fall into it.

A dream so contagious that one enters into a kind of parasocial relationship to the dreamer.

The phrase captures the idea that our imaginations are often limited by the structures and systems we live within, making it difficult to envision alternatives to whatever your favorite bugaboo is — capitalism or some other dominant ideological apparatus.

Etcetera.

Probably since at least the 1995-2005 era of my participation in graduate studies, of which four of those years were actually spent in active study and/or writing, the sentiment of the phrase I’m describing was a guiding principle. Its relation to the main humanities grad student’s epistemology (postmodernism) of the day was something I used (or misused) in order to make sense of my objects of study (technology, engineering, video games, simulations, visual culture and their intersections). The phrase and its sentiment was a kind of undergirding purpose for studied critique of the technocultural world we live in.

It made it easy to be cynical about the future and, certainly in the spirit of the rebel budding academic, antagonistic towards the various powers, nefarious dreamers, and capital-backed agents that enthusiastically articulated a present that tends towards a particular dreamers dream of the future.

That particular dream?

Well, as always dreams are hard to describe. They are feeling mostly, I think.

This one is a vivid and compelling one to a guy who came into consciousness in a moment in which computers, networks, space travel, cyberpunk, Star Trek, space shuttles, and fighter jets were, like..‘whoa..cool!’

To a degree, I think the dream is the one we register today, at least here in California.

Maybe most of the USA.

It’s the one that is a kind of techno-optimism, a kind of techno-solutionism, a kind of techno-enthusiasm that is so infectious that it becomes a kind of religion.

So, why am I writing about this? This dispatch about dreams and the future?

Because it matters to the degree that those (of us) with an ability to articulate our hopes for a more habitable future do so responsibly.

What is ‘responsibly’?

It means considering how our representations of futures are or could be received/registered/made-sense-of/felt by those who could use more habitable visions of the future. (Like all the kids who have inherited and now fully inhabit a particularly antagnoizing future-dream.)

It is a solemn responsibility that deserves care and diligence.

My mentor and Ph.D. advisor Donna Haraway’s book length argument to ‘stay with the trouble’ does not mean to cause more trouble or be an antagnoizing shit-starter.

Rather, at least in my reading of it, it is at a minimum a call to avoid a fatalistic or escapist position.

That is — less dystopian tales, and less utopian rainbows and herds of unicorns.

The artist who plays with the future and for whom the future is a medium and material, and casts a deliberately dark future of armed conflict or some such, is playing into the hands of the very forces that are at work to make the world a less habitable place. It is antagonistic. It is like taking the bait of the bully who is trying to pick a fight because they only know how to fight. And they know a fight will amplify and darken the world to their benefit alone.

Your responsibility at this moment is to create visions of a habitable future, and to imagine the non-conflict future lest we ramble in frustration right into that abysmal and bottomless canyon.

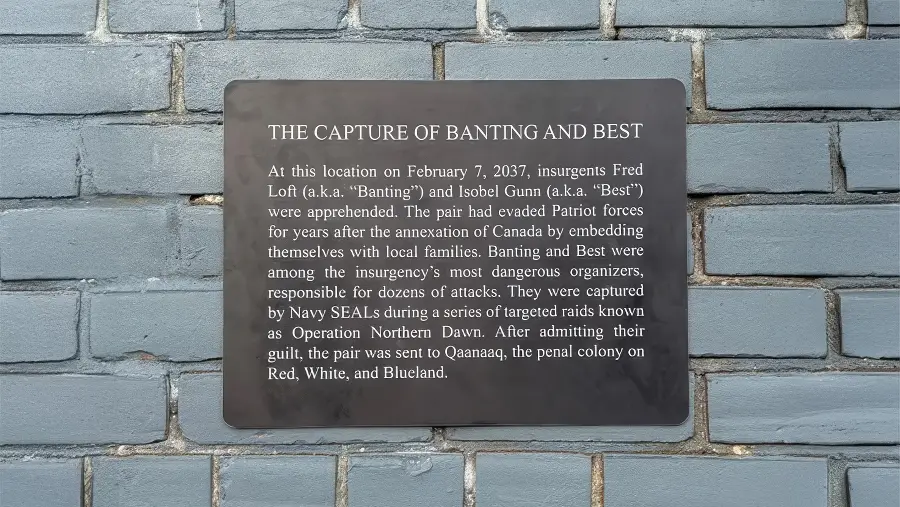

So I say all of that to say this: I have a somewhat art-critical objection to the work that a few people have generously shared with me recently.

When I first saw it, there was that — oooh! cool! — feeling that was tinged with a note of professional jealousy.

“Dang. Good one!”

That quickly faded as the more analytic side of my consciousness reminded me that this artifact from some possible future was from a future in which there was armed conflict between the USA and Canada.

Here I was, for an embarassingly long split-second, staring at the bottomless canyon instead of the trail, future-fantasizing about the weight and heft of a sniper rifle, the smell of cordite, out on recon patrols, night-vision optical gear, lots of velcro, a band of brothers, and shit like that.

What the absolute fuck?

Is this the best that we can do?

Please stop.

We are responsible for the future and for imagining it ‘otherwise’.

You can safely assume that no one the fuck else is.

There’s no special working group in some organization somewhere that’s going to reveal their plan to fix shit with some super charasmatic leader.

There’s no scene like in the movie where some beneficent orb or disciplining monolith or talking pink cloud lands in Central Park to come and straighten everyone one the fuck out.

We have to imagine harder than that.

Otherwise, accept that you may have had some responsibility in this terrible future coming to pass. Not you alone. But you certainly didn’t help.

We have to imagine a future that is not a dystopian nightmare, but one that is full of possibility and hope.

To render a future vision where there had to be sniper stations at a hot dog stand during a battle or occupancy or whatever the fuck is going on here?

Well, that is just the product of a deficient imagination — or the product of a kind of parasocial relationship to the dark forces of the world.

Like..what is this even?

“I see you dark force dudes and this is what I see you instigating. This’ll teach you! I’ll help write your playbook out, in a style and genre you’ll appreciate!”

And those dark forces are like..“Oh, cool. Hadn’t thought about the hot dog stand. Let me add that to the ROE. ‘Hot dog stands. Viable snipers nest. Check!’”

I get it. The feeling of inevitable doom is a product of a lack of not just imagination, but the result of a lack of a sense of agency — and even deeper, a forgetfulness to the fact that we actually have this remarkable ability to imagine the world (and its futures) otherwise.

There was a time when the clarion call of dystopian near future science fiction may have been seen as helpful. A way to warn us of the potential consequences of the world we live in.

But now?

Feels like the lessons of Alex Blechman’s Torment Nexus has been forgotten by well-intentioned futures practitioners. (In this case, a high-functioning creative with a bent towards translating current state into future state, which we might describe as a kind of futurist with a creative consciousness rather than the more analytic futurist of the ‘Seven Horizons’ — or whatever — variety.)

This is a bit like sniffing spoiled milk over and over again to absorb how bad it smells. Echoing and reiterating the same old tropes of dystopia and apocalypse and bloody corpse-strewn conflict is not a way to imagine a better future. It is a way to reinforce the very systems that are causing the problems we face.

It’s time to imagine harder.

And that’s what I have to say about that.