Contributed By: Julian Bleecker

Published On: Nov 26, 2024, 10:24:13 PST

Updated On: Nov 26, 2024, 23:06:44 PST

This essay appears in the book Practices of Futurecasting, published by Birkhauser. The book is a collection of essays that explore the intersection of design, storytelling, and future studies, with contributions from various authors in the field. You can find the book available on the Birkhauser website and likely available for order through your local independent book shop or online.

Preamble

When Tobias and I sat down to write Stories to Imagine Alternate Futures, our goal was to share how we see storytelling as a vital, transformative tool for rethinking the future. In the world of foresight and future studies, there’s a tendency to lean heavily on models, data, and policies—tools that are valuable but often fail to connect with the deeply human experience of what it means to imagine “what comes next.” We wanted to highlight how stories, especially speculative ones, create a space for people to explore alternate futures in ways that are tangible, emotional, and even unsettling.

In the essay, we dig into the practice of Design Fiction, which is a kind of sandbox for future possibilities. It’s not about predicting what will happen but creating immersive provocations that let us test out ideas, values, and even fears in a low-stakes way. For example, we write about Abundance, a speculative project imagining a regenerative urban culture in London. It’s a world where food imports are tightly controlled, and energy use is deliberately constrained. These scenarios aren’t just technical exercises—they’re ways of asking, “What kind of world do we want to live in?” They’re opportunities to challenge the defaults of what people assume the future will be, whether it’s endless technological progress or unchanging cultural norms.

We also explore the unique feedback loop between speculative storytelling and real-world innovation. Science fiction doesn’t just reflect our dreams and anxieties about the future—it actively shapes them. Think about how the gadgets in sci-fi films often inspire real technological advancements, or how games and stories subtly shift our collective sense of what’s possible or desirable. But we also argue that the work of imagining futures needs to go deeper than shiny tech or dystopian clichés. It needs to include voices and perspectives that aren’t always part of these conversations, so the future isn’t just a projection of the same dominant narratives we see today.

Writing this piece was a way for us to articulate why we believe storytelling is so powerful—not just as a way to entertain but as a way to make change. It’s a call to arms for anyone who cares about the future to embrace the messy, imaginative, and deeply human process of shaping it. The future isn’t written; it’s something we build, story by story. And those stories? They might just make all the difference.

Introduction

In this essay we want to argue for taking imagination seriously as a driver of better futures work and how design techniques such as Design Fiction and/or speculative design can be the interface between the easily-dismissed faculty of imagination and the professional services of foresight, forecasting, strategy and planning.

Imagination is a vital and existentially advantageous capability that humans possess. However, it is not often treated as a driving factor in the ways we approach, work upon, and materialise the kinds of futures we desire to inhabit. Imagination is integral to any meaningful work that desires to sense-into possibility, and can be done so directly through practices like Design Fiction, speculative design, futures design and other emerging methodologies and approaches.

In this essay we highlight how a lack of imagination stymies futures work and argue that it therefore should play a more crucial and central role in the activities of domains of foresight, strategy, policy, and planning. Our paper aims to expand the imaginative potential of organisations, institutions or individuals that rely upon casting their lot into possible futures that have implications at planetary and species scale. These futures practices, in dealing with complexity at massive scale, can benefit enormously by drawing on the common and empowering potential of imagination through design as a tool for materialising abstract notions and challenging the status quo .

Serious Imagination

In the serious world of foresight, strategy, policy and planning one rarely hears the word ‘imagination.’ It’s dismissed as either hard to measure or verify, making it inappropriate for the sciences of business and policy; or it’s a luxury; superfluous to the needs of the organisation or project. However, we suggest that it’s arguably the most critical and consistent component of futures work because - even in the most mundane of foresight projects - we constantly use imagination. For instance, in the interpretation of a prediction, the mind can’t help but imagine future interactions, opportunities or threats that emerge. The sense of unease that accompanies uncertainty and risk or the relief that goes with a confident projection are all products of imagination that connect cause with effect and pattern with meaning. All work in the future necessarily requires imagination insofar as the future hasn’t happened yet. No other animal that we know of (other than corvids) can use its imagination to simulate a scenario outside the present (Burgess, 2017) and some even attribute humans’ uniquely prevalent high stress levels to an overabundance of imagination; imagining the worst, how others might be thinking of us or all the ways in which we might suffer from speculative maladies or misfortunes. (Sapolsky, 2004)

In other words, whether we like it or not, we are constantly engaged in futures by imagination. This makes serious engagement with imagination and imaginative potential a fertile site for critical and meaningful futures work. . Further, imagination introduces the constraints by which ‘serious’ futures work can operate: We’re only able to respond to the futures we can contemplate through our imaginings, and so what we’re able to imagine and who is permitted to imagine predefines the futures we can build and anticipate.

Foreclosed Imaginaries

We are notoriously poor at imagining beyond the foreclosed imaginary futures space laid out before us. For instance, coverage of technological advances in labour for the last 150 years has largely focussed on how they will lead to mass joblessness even as general employment continues and in fact increases with a growing population and more people entering the workforce over the 20th century. (Autor, 2015)

Why is an imaginary future of mass joblessness so prevalent and easy to contemplate while the opposite - a world in which we no longer have to work at all - is generally dismissed as fantasy? We might infer that the challenge of contemplating a world without work, or even imagining what ‘work’ itself might mean in such a toil-less world is not because such a concept is impossible, but that such has not been imagined to the degree that it is considered credible enough to be sensible, described, represented, and discussed reasonably. This is evidence of how we find it so easy to update our technological settings and context but difficult to challenge social norms. In modern capitalism; the conflation of life with work has made it impossible to extricate the two.

In another example, why can we so easily imagine green cars, robot cars, smart cars, shared cars, hydrogen cars or cars 3D printed from mushrooms, but imagining that we might design out or abolish the car from our cities, saving the lives of up to 1.35 million people a year (CDC, 2023) is deemed ludicrous or unachievable? Again, the car is so thoroughly embedded in our society, infrastructure, cities and, indeed, our imaginaries, that - after only three or four generations and without concerted effort - we cannot fathom a world without it, even though the historical record of human civilisation is dominated by thriving carless societies.

Critical futures scholars suggest that a paucity of imagination applied to futures work simply reinforces in an “extended present” (Sardar & Sweeny, 2016) or the tendency we have “to read the future as a fancier version of the present.” (Borup et al., 2006, p.288) Put simply, we are like the fish in the David Foster Wallace parable who are asked how the water is, to which they wonder, “What the hell is water?” Without imagination, we are unable to consider that we may be within an ontological volume that seems so fixed that it is impossible to imagine another existence.

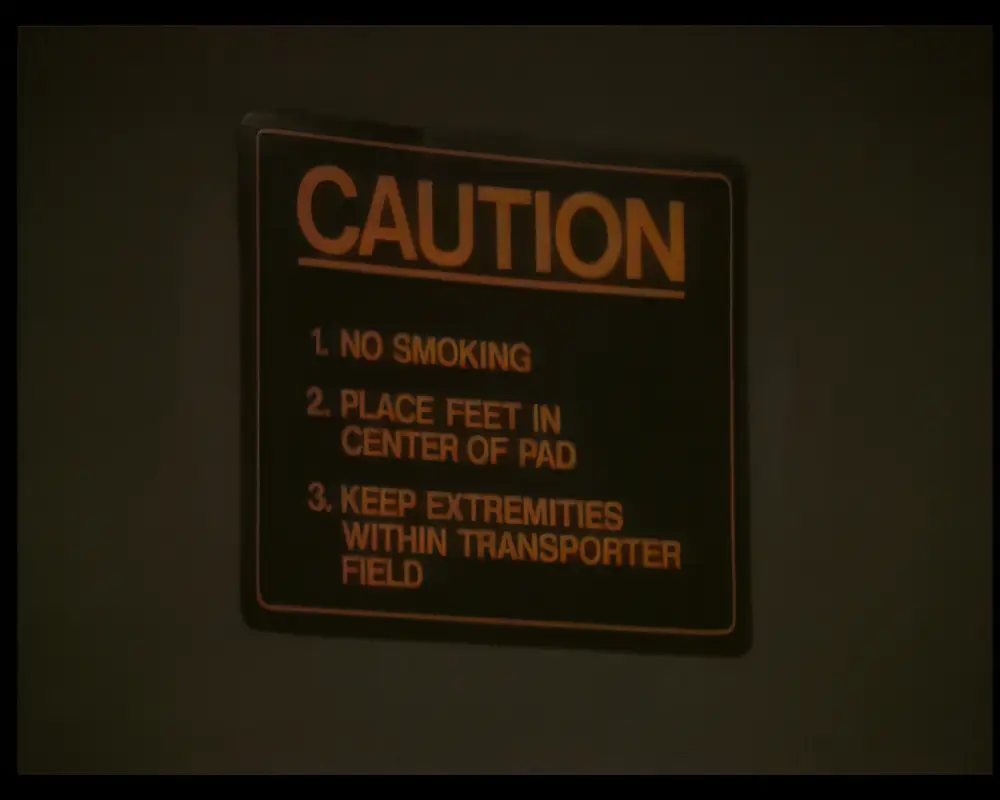

In a historic example, the designers of Star Trek III (1984) could imagine a future two hundred years away in which a technology exists that could disassemble someone into atoms, send them across space and reassemble them again at the other side but they couldn’t imagine a society where smoking was eradicated. Again; we have a predilection towards easily imagining radical technological advance while we find it difficult to challenge social norms.[^1]

Scholars of social constructionism call this ‘stabilisation;’ (Pinch & Bijker, 1984) the point at which a new or emerging technology, policy or trend achieves general acceptance such that it is assumed there are no viable alternatives, and no need (or credible faculty) to imagine the world otherwise. Returning to AI and automation, a recent review of ethics guidelines found that the technology is imagined as the result of “world-historical forces of change—inevitable seismic shifts to which humans can only react…It is taken for given that AI/ML technologies are a) coming and b) they will replace a broad swathe of human jobs and decisions… Consequently, ethical debate is largely limited to appropriate design and implementation – not whether these systems should be built in the first place.” (Greene et al., 2019, p.6) In other words, the imaginary of a future of AI is so stabilised that public debate mostly centres on reducing the potential and real harms it inflicts rather than questioning or imagining alternatives to the fundamental assumptions about what kind of AI we have, for who, what and why?

This gets us to the ‘who’ of imagining. “[I]maginaries are at once products of and instruments of the coproduction of science, technology, and society.” (Jasanoff, 2015, p.19) For science, technology and society, those with the wealth and access to labs, demo stages, press coverage, policy research, users’ eyeballs, advertising, legislative forums and the right conferences are the producers; given the privilege to contest their imaginary futures in public and fight to build consensus around their own version of the future and stabilise it. (Pinch & Bijker, 1984)

It is often the role of good foresight to try and challenge this stabilisation and reflect real uncertainty; to broaden perceptions of the future; to consider the possible outside of the probable or proscribed and use this breadth of understanding to make strategy resilient, write adaptable policy or rigorous business plans. However, most people don’t encounter the future through these prioritisation exercises of policy, strategy, foresight and business planning. (Kerr, 2020) The common experience of the future isn’t in spreadsheets, white papers, flow charts and diagrams but in the stuff and stories of the world. Many studies have shown the influence of science fiction movies, video games and TV on real-world innovation and how it shapes public demand for future products and services (E.g. Bassett et al., 2013; Goode, 2018; Romic, 2022) and then how these demands reshape policy and strategy in a mutual feedback loop.

So, how can we draw on this common understanding of stories and fictions about change to re-imagine the taken-for-granted? How do we imagine alternatives to the worlds we inhabit, even if just for the sake of invigorating the capacity we all have to imagine that the worlds we inhabit can be otherwise?

Design Fictions

Tthe question for practitioners is how to tell alternative stories that dislodge status quo futures and challenge the commonly-held beliefs that underpin them. In a world hungry for stories, how can we liberate the future and empower more people to have a voice in shaping it? How might storytelling through design be used to create new spaces for imagination?

In the quest to expand the scope of imagination in futures work, various methodologies have emerged to challenge the status quo and offer creative thinking to the task of exploring and representing possible futures. Two of these methodologies; Design Fiction and speculative design, have gained prominence for their ability to help us sense-into multiple and varied possible futures with rich, acute, and vivid tangibility. These approaches go beyond traditional forecasting and report-generation to problematise dominant future imaginaries, providing space for creative innovation, discovery of future unknown unknowns and allowing immersion and exploration of unexpected and unconventional ideas.

The increasingly popular practices of Design Fiction and speculative design indicate a wider acceptance that problematising, questioning and challenging our assumptions about the future are just as important as finding rich data to back up our projections. Design projects like Abundance, produced by Arup Foresight for London Design Festival 2022 challenge the accepted norms of the future of our cities through visual storytelling and careful consideration of the design and material experience of the future. (Arup, 2022)

Abundance is set in a future London in which the city has transitioned to a regenerative urban culture. Regenerative design imagines humans as part of nature rather than above it; that the way we live, interact and consume should contribute to the health and resilience of the natural ecosystem around us. The premise is that this would result in a cleaner, healthier and more resilient way of life and experience for everyone and everything, but there are trade-offs. For instance, you might only be able to buy food grown locally to reduce the carbon cost of importing it and might have to eat as a larger group to reduce the fuel costs of cooking. You might not be able to travel wherever you want, whenever you want or use as much energy as you like. The shift to a regenerative world is also a shift in values; from consumption, individualism and extraction to contribution, restoration and community.

However, on the surface these ideas can be quite abstract or intimidating. Regenerative design is a growing field with some strong principles and few case studies. So, importantly, Abundance takes the abstract and complex notions of life in a regenerative future and materialises them. Design scholar Carl DiSalvo has shown how people assemble around ‘issues’ and those issues are often material; the closure of a factory, the building of a new block of flats, the moving of a school, the closing of a service. (DiSalvo, 2009) When dealing with somewhat ‘immaterial’ issues like alternative futures, the future of AI, or how we might live differently he shows how design can materialise these abstract notions into issues that people can assemble around, discuss and deliberate over. By examining the lived experience of an average person and eschewing a heroic narrative that might be seen in mainstream TV or film, Abundance invites the audience to compare the life of this future fiction to their own and engage with the way a humble corner of the future really plays out; in the domestic, social, political and community spheres, not with big heroes; human or technological.

But designs and stories alone aren’t enough. We also must address the ‘who’ of imagining. For a healthy society, we must empower more people to create and imagine. Work from organisations like Camden Council and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in the UK (Imagination Infrastructuring, n.d) point towards the legitimisation of ‘imagination’ more generally as a tool of collective decision-making and civic participation in futures by providing the space, time and support for more people to contribute to imagining solutions to social issues.

It is in the interest of those shaping possible futures to challenge “transhistorical continuity; The sense that we are on an inevitable future path with one particular version of ‘progress.’” (Romic, 2022) As Frederic Jameson observed: Most futures work “does not seriously attempt to imagine the “real” future of our social system. Rather, its multiple mock futures serve the quite different function of transforming our own present into the determinate past of something yet to come.” (Jameson, 1982, p.152) For many, the future feels inevitable; the coming of AI, the release of the next car or smartphone, worsening weather and climate – a long line of incremental ‘improvements’ on an extended present stretching infinitely into the status quo future.

However, there are many precedents of where the promises and inevitability of status quo futures have been reversed; nuclear proliferation happily stopped. Human cloning could have been a part of our world but was swiftly and universally prevented. Even further back, the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, modern democracy and then thinking forward; the green transition. All seem impossible until the right story inspires leaders and decision-makers that other worlds are possible. As science fiction writer Ursula Le Guin reminded us: “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings.” (Le Guin, 2014)

References

Arup. (2022) Abundance

Autor, D.H. (2015) ‘Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), pp. 3–30. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.3.3.

Bassett, C., Steinmueller, E. and Voss, G. (2013) Better Made Up: The Mutual Influence of Science fiction and Innovation. Working Paper 13/07. London: Nesta, pp. 1–40.

Borup, M. et al. (2006) ‘The sociology of expectations in science and technology’, Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 18(3–4), pp. 285–298. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320600777002.

Burgess, M. (2017) Calculating, plotting ravens make plans for their future, WIRED. Available at: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/ravens-plan-future (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

CDC (2023) Road Traffic Injuries and Deaths—A Global Problem, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/global-road-safety/index.html (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Cyran, R. (2023) ‘AI offers leisure, if not happiness’, Reuters, 12 May. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/breakingviews/ai-offers-leisure-if-not-happiness-2023-05-12/ (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

DiSalvo, C. (2009). Design and The Construction of Publics, Design Issues 25(1), p.52

Elish, M.C. and boyd, danah (2018) ‘Situating methods in the magic of Big Data and AI’, Communication Monographs, 85(1), pp. 57–80. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1375130.

Goode, L. (2018) ‘Life, but not as we know it: A.I. and the popular imagination’, The Journal of Current Cultural Research, 10(2), pp. 185–207. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.2018102185.

Greene, D., Hoffmann, A.L. and Stark, L. (2019) ‘Better, Nicer, Clearer, Fairer: A Critical Assessment of the Movement for Ethical Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning’, in Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Available at: https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2019.258.

Imagination Infrastructuring. (n.d.) ‘Imagination Infrastructuring’ (Accessed: 18 October 2023)

Jameson, F. (1982) ‘Progress versus Utopia: Or, Can We Imagine The Future?’, Science Fiction Studies, 9(2), pp. 147–158. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474248655.

Jasanoff, S. (2015) ‘Future Imperfect: Science, Technology and the Imaginations of Modernity’, in Dreamscapes of modernity: sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. Chicago ; London: The University of Chicago Press.

Kerr, A., Barry, M. and Kelleher, J.D. (2020) ‘Expectations of artificial intelligence and the performativity of ethics: Implications for communication governance’, Big Data & Society, 7(1), pp. 1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720915939.

Le Guin, G., Ursula K. (2014) Ursula K. Le Guin — The National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Available at: https://www.ursulakleguin.com/nbf-medal (Accessed: 8 May 2023).

Pinch, T.J. and Bijker, W.E. (1984) ‘The Social Construction of Facts and Artefacts: or How the Sociology of Science and the Sociology of Technology might Benefit Each Other’, Social Studies of Science, 14(3), pp. 399–441. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/030631284014003004.

Romic, B. (2022) ‘Negotiating anthropomorphism in the Ai-Da robot’, International Journal of Social Robotics, 14(10), pp. 2083–2093. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-021-00813-6.

Sapolsky, R., (2004) Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Value creation in the metaverse (2022) McKinsey. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/growth-marketing-and-sales/our-insights/value-creation-in-the-metaverse (Accessed: 18 October 2023).

Sardar, Z. and Sweeney, J.A. (2016) ‘The Three Tomorrows of Postnormal Times’, Futures, 75, pp. 1–13. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2015.10.004.

Suchman, L. and Weber, J. (2016) ‘Human–machine autonomies’, in Autonomous Weapons Systems - Law, Ethics, Policy. Autonomous Weapons Systems - Law, Ethics, Policy, European University Institute, Florence, pp. 75–102. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781316597873.004.

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (1984) Paramount Pictures

1. The world of Star Trek also has an interesting relationship with work: The Stark Trek universe is post-scarcity where people can travel and settle freely and anything can be materialised at will. Yet in order to drive the drama, various tropes of capitalism are leveraged in order to introduce conflict over space, resources or power. In theory, no one in the Federation needs to work but they do and despite this there’s almost no political discourse between characters within the Federation.