Contributed By: Julian Bleecker

Published On: Nov 18, 2024, 12:14:01 PST

Beatriz da Costa (un)disciplinary tactics caught me off guard. I found myself in Los Feliz, just on the other side of downtown Los Angeles, and so decided to amble over to my favorite bookstore there, Skylight Books — the art & design annex nestled in a narrow storefront adjacent to the main store and inevitably just next to this or that street busker. I wasn’t looking for the book. In fact, I had no idea it existed. And then I saw her name and did a double-take.

I knew Beatriz back in the heady days of the early 2000s when there was plenty of experimental art+technology work happening. That neologism has been a thorough-going container for a particular kind of R&D work; a kind that is often overlooked as to its potential to sense-make the new gewgaws that have yet to be made sense of.

Flipping through it I saw an old friend, and others. It was like a Proustian reverie reminding me of times in New York City at Eyebeam and working under a Creative Time grant when experimentation was encouraged.

It was before someone figured out how to shove a credit card into a web browser.

Having this book has felt like feels like sitting down with old friends who were tirelessly questioning the world around them, offering sharp insights and creative provocations — and making stuff to answer questions and, well — just to wonder. This book serves as both a retrospective and an intimate portrait of an artist who defied boundaries and expectations, seamlessly blending art, activism, and technological experimentation.

Beatriz da Costa’s work was fundamentally about disruption - not in the trendy, corporate sense, but as a genuine act of challenging hierarchies, questioning power structures, and reclaiming agency in technological development. Her “(un)disciplinary” tactics deliberately blurred lines between scientific research, artistic experimentation, and public engagement. She didn’t just critique systems; she actively reimagined them, creating provocative projects that transformed audiences into participants and collaborators.

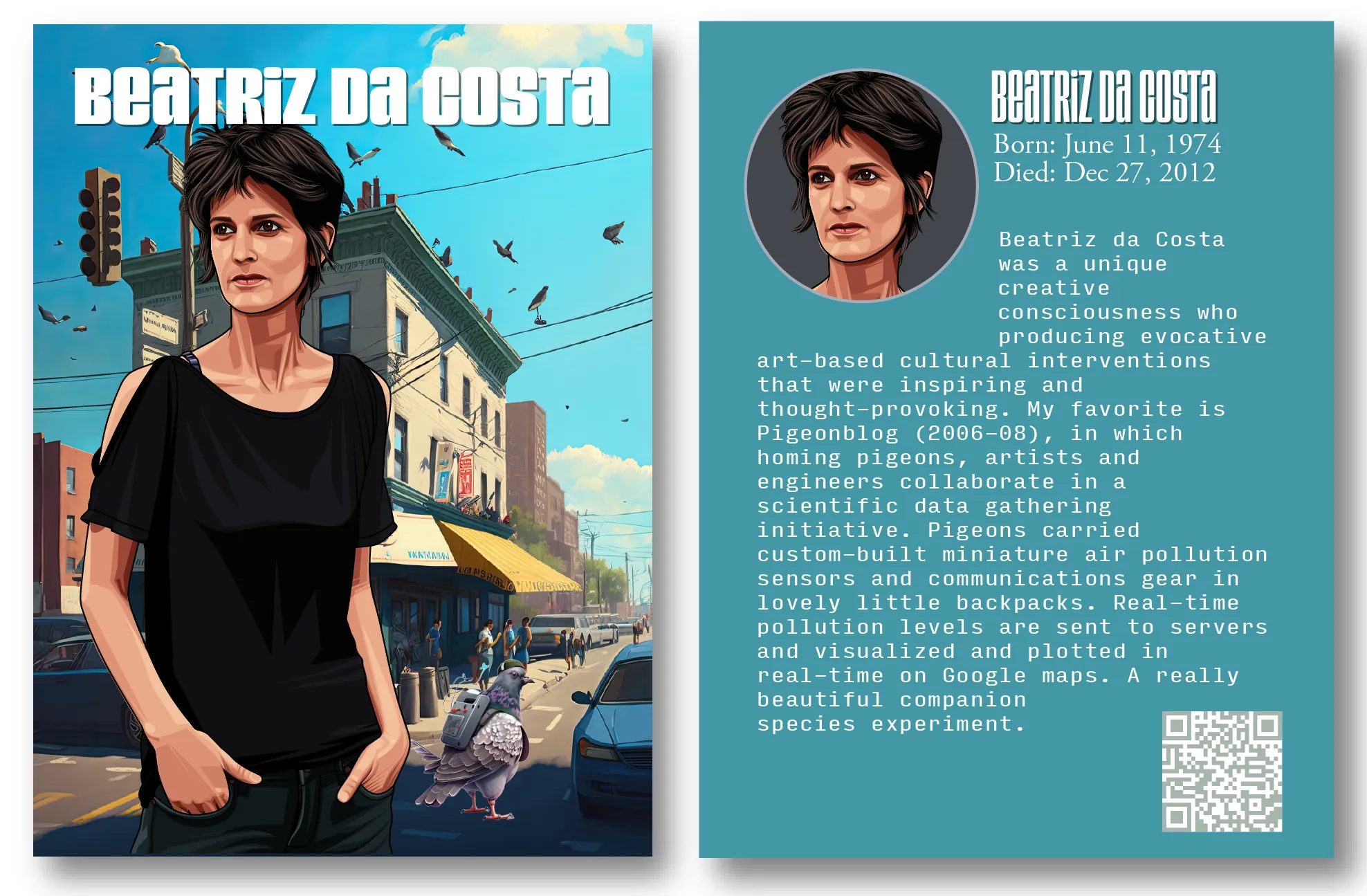

Projects like her applied companion species integration PigeonBlog, in which pigeons equipped with air quality sensors in little backpacks they wear collected environmental data, exemplify her art+technology approach. Pigeon Blog wasn’t just about the technology or the data. Rather it was about reframing how we understand our relationship to the environment in which that environment also consists of other collaborating, co-occupants that we call ‘other species’. By appropriating tools like Google Maps to create participatory experiences, da Costa subverted corporate platforms to imagine alternative futures — what we might call ‘applied design fiction.’ Her work anticipated many of the conversations we’re still having today about the Internet of Things and citizen science, making her a prescient voice in contemporary art and activism.

Beatriz’s collaboration with collectives like Critical Art Ensemble and Preemptive Media further underscores the belief she held in collective knowledge production and collaboration. The project Free Range Grain tested genetically modified organisms. Zapped! did the work of demystifying RFID surveillance. In all of these the trajectory was to transform intimidating technologies into tools for public empowerment, unpacking and decomposing the opaque techniques. In a beautiful and scholarly way, her projects bridged theory and practice, engaging audiences in debates about topics of the day — biotechnology, surveillance, environmental justice, and more.

Perhaps most poignant is how her personal experience shaped her later works. Beatriz was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer. Like a true researcher and public intellectual, she turned her illness into an opportunity for public dialogue. Pieces like Dying for the Other, a video triptych juxtaposing her treatment with laboratory research on animals, didn’t just reflect her struggle but interrogated the ethics of medical research and its reliance on animal testing. These works exemplified her ability to merge the deeply personal with the broadly political, using her own story to highlight systemic inequities in healthcare and research.

What emerges from this book is not only a celebration of her art but a blueprint for how creative practice can intervene in technological development. Her installations were speculative and functional, using open — source principles to make scientific tools accessible while fostering critical dialogue. From creating medicinal gardens with The Life Garden to critiquing the commodification of healthcare in The Anti-Cancer Survival Kit, da Costa modeled how artists could address urgent societal challenges with empathy and imagination.

The contributors to this book—scholars, artists, scientists—paint a vivid picture of da Costa’s legacy as a boundary — breaking figure. Her work reminds us that art can be more than aesthetic; it can be a vital space for public research, social critique, and technological experimentation. Beatriz da Costa didn’t just make art; she created new ways of seeing, thinking, and participating in the world.

Reading this book feels like a call to action—to reimagine the role of art, to challenge entrenched systems, and to prototype futures that are equitable and participatory. For anyone interested in the intersections of art, technology, and activism, this book is a must — read. It’s a reminder that the boundaries we often accept as given are there to be crossed.