Project Summary

PDPal is a series of public art projects for the Palm™ PDA, mobile phone and

the web. It has pushed at the notion of mapping, attempting to transform your

everyday activities and urban experiences into a dynamic city that you write.

PDPal engages the user through a visual transformation that is meant to

highlight the way technologies that locate and orient are often static and

without reference to the lively nature of urban cultural environments. In

response to the plethora of mapping projects that have utilized GPS and

measurable cartography, PDPal has been anti-geographic and anti-cartesian,

preferring to experiment with the construction of relative, emotionally based

systems that ask what makes social or personal space.

PDPal responds to

the century-old idea of the urban explorer — from Baudelaire's «flaneur» (late

19th century); the Dadaists' public performances of nothing, sometimes called

«deambulations» (1921); Benjamin's texts on the urban wanderer (1920's); the

Situationists' algorithmic derives; Hakim Bey's Temporary

Autonomous Zones that spring up in the cracks of urban regulations, and

are opportunities for brief piracy of a place; and contemporary work in

psychogeography — all deliberate projects of 'getting lost' in the city, thus

restoring it to a great dense space of wonder, not just a locus of labors.

Project Semantic Tags

APPART+TECHNOLOGYPROGRAMMINGPSYCHOGEOGRAPHY

PDPal was a series of public art projects for Palm™ PDAs, mobile phones, and the web. In contrast to GPS and measurable cartography, PDPal embraced anti-geographic and anti-cartesian approaches, exploring emotionally-based systems to define social and personal space. It revisits the concept of the urban explorer, from Baudelaire’s “flaneur” to Dadaists’ “deambulations,” Benjamin’s urban wanderer, Situationists’ “derives,” Hakim Bey’s “Temporary Autonomous Zones,” and contemporary psychogeography. PDPal aimed to reclaim the city as a space of wonder, not just labor

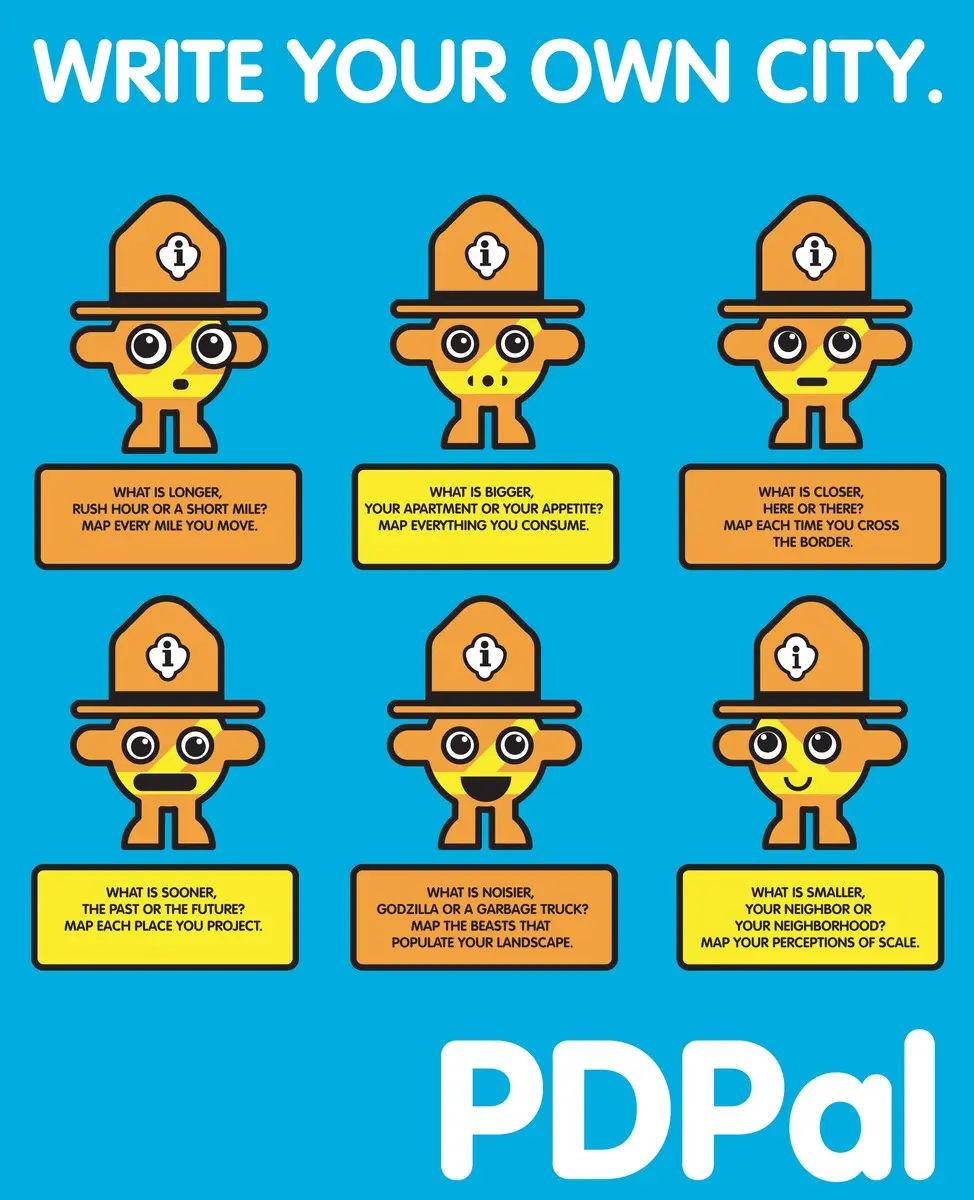

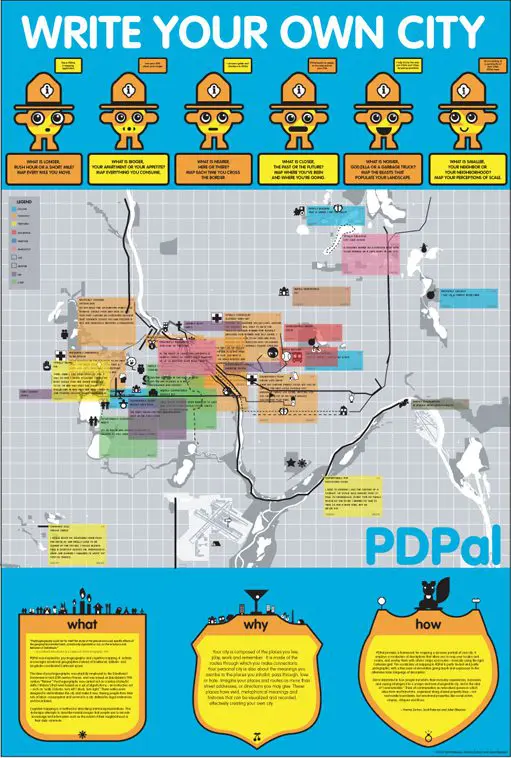

The goal of PDPal is to use mobile and networked platforms as a mediating and recording device that reactivates our everyday actions, transforming them into a dynamic portrait of our urban experience: a way of “writing our own cities.” At the core of the PD Pal application is an “Urban Park Ranger” (UPR), an individual software persona who, once downloaded into a PDA, encourages the owner to log his or her momentary experiences, actions, proximities, and perceptual phenomena in iconic broad strokes as she moves about the environment. The UPR helps to create personal and idiosyncratic maps of our “temporary Personal Urbanisms.” PDPal provides the tools to create maps as place-based memory shells or to stand as a narrative shorthand - marking personal intervals of place and experience, which can later be uploaded to a central website and shared as a made-up city of individuals who share a subjective and poetic language in ways that can render the visible and invisible.

OVERVIEW

”To cover the world, to cross it in every direction, will only ever be to know a few square meters of it… tiny incursions into disembodied vestiges, small incidental excitements, improbable quests congealed in a mawkish haze a few details of which will remain in our memory. And with these, the sense of the world’s concreteness…no longer as a journey having constantly to be remade, nor the illusion of a conquest, but as the rediscovery of a meaning, the perceiving that the earth is a form of writing, a geography of which we had forgotten that we ourselves are the authors.”

Georges Perec, ‘Species of Spaces’

PDPal is an ongoing series of public art projects for the Palm™ PDA, mobile phone and the web. It has pushed at the notion of mapping, attempting to transform your everyday activities and urban experiences into a dynamic city that you write. PDPal engages the user through a visual transformation that is meant to highlight the way technologies that locate and orient are often static and without reference to the lively nature of urban cultural environments.

Your own city is the city composed of the places you live, play, work, and remember. It’s made of the routes and paths through which you make connections. Your city is also about the meanings you ascribe to the places you inhabit, pass through, love or hate. You imagine those places and routes as more than a street address, or directions you may give. These places have vivid, metaphorical meanings and histories that PDPal allows you to capture and visualize imaginatively, effectively writing your imaginary city.

In response to the plethora of mapping projects that have utilized GPS and measurable cartography, PDPal has been anti-geographic and anti-cartesian, preferring to experiment with the construction of relative, emotionally based systems that ask: what makes social or personal space. PDPal responds to the century-old idea of the urban explorer: from Baudelaire’s “flaneur” (late 19th c); the Dadaists’ public performances of nothing, sometimes called “deambulations” (1921); Benjamin’s texts on the urban wanderer (1920’s); the Situationists’ algorithmic “derives”; Hakim Bey’s “Temporary Autonomous Zones” that spring up in the cracks of urban regulations, and are opportunities for brief piracy of a place; and contemporary work in psychogeography - all deliberate projects of “getting lost” in the city, thus restoring it to a great dense space of wonder, not just a locus of labors.

EXHIBITION HISTORY

Eyebeam Atelier, NYC “Beta Launch” show and artists’ residency 2002

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN 2003

Transmediale Festival, Berlin 2003

University of Minnesota Design Institute, “Twin Cities Knowledge Maps” 2003

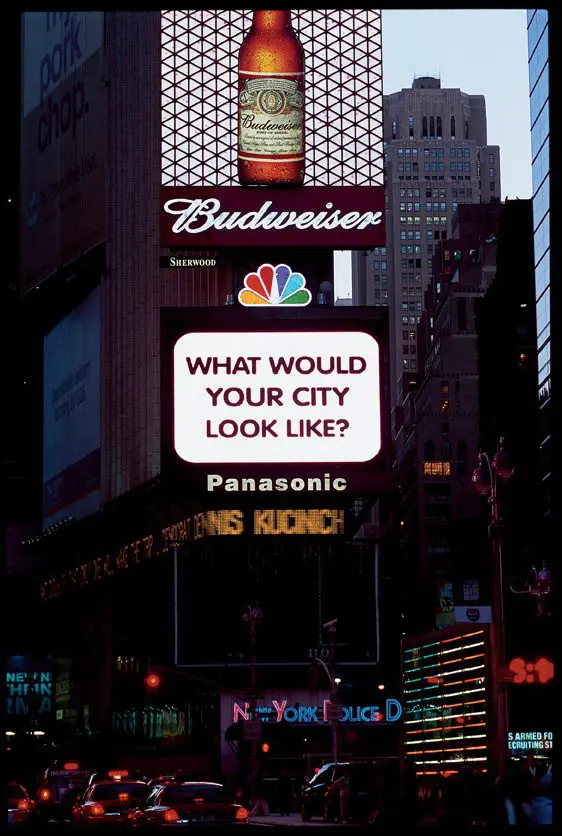

Times Square, NYC “Creative Time Presents” 2003-2004

Whitney Museum of American Art, Artport 2003

Walter Phillips Gallery, The Banff Centre, Alberta Canada “Database Imaginary” 2004

PROJECT HISTORY

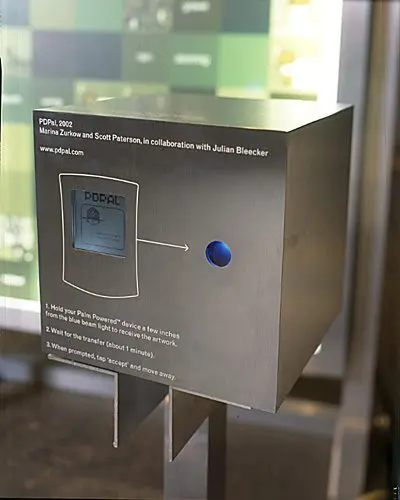

Presented at Eyebeam Atelier in New York City. In this first version of PDPal, a user beamed an app to their PDA from the installation, much resembling a bus shelter with a two-sided duratrans. The user would input criteria about their social, tactile, weather, and speed conditions, and the PDA app would return a pictographic “haiku.” there was further room for a short text annotation. Users could share these haiku” by beaming them to one another.

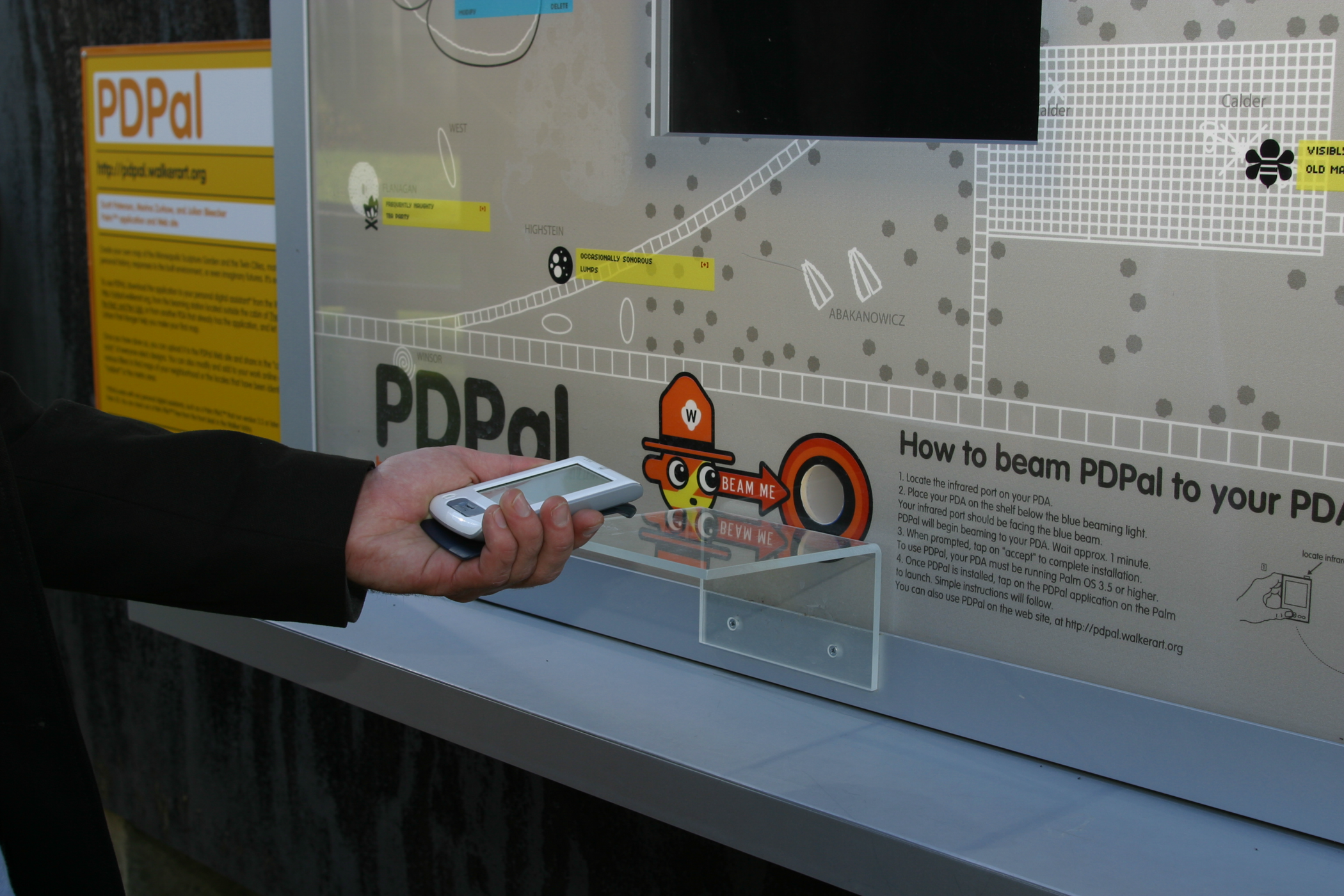

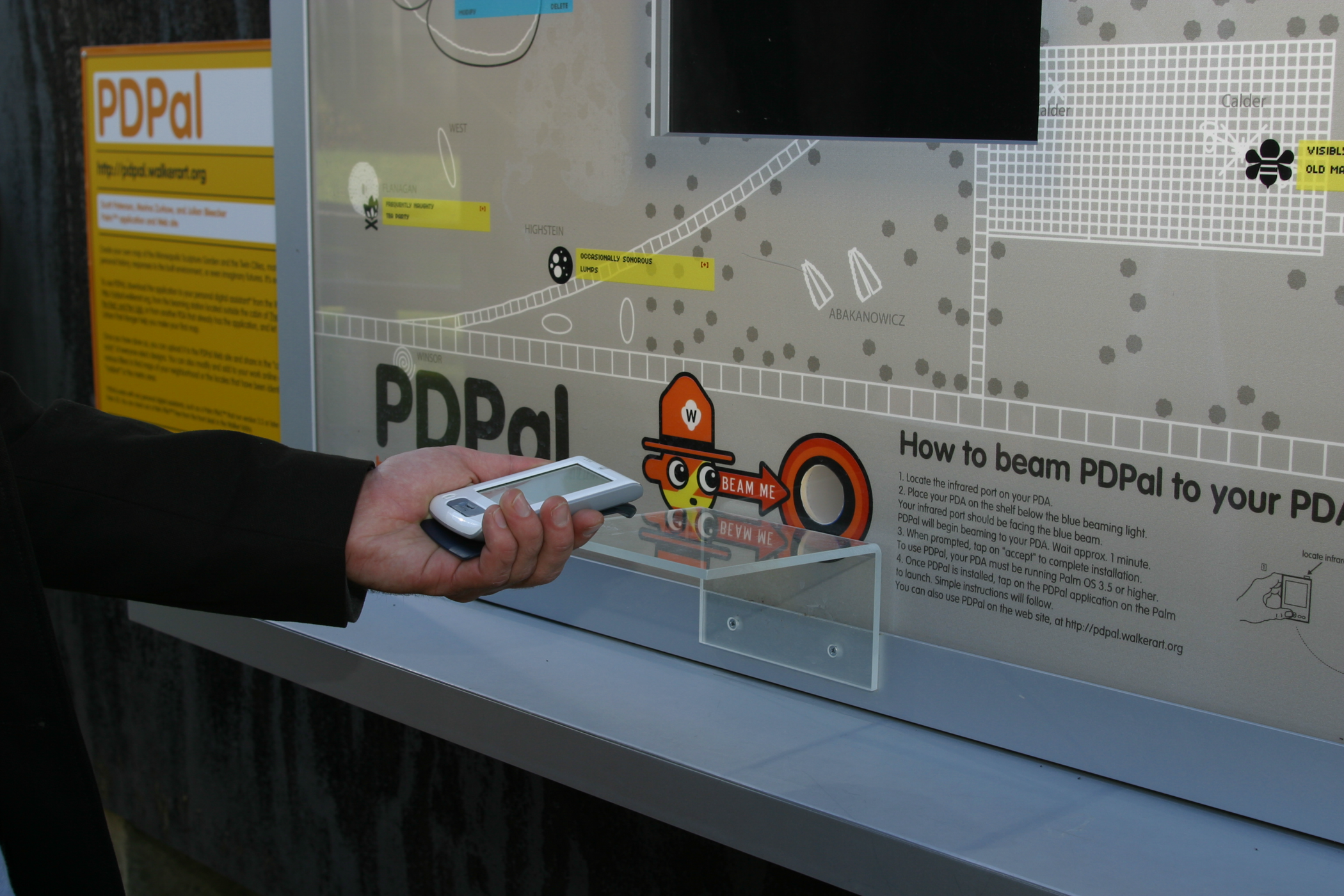

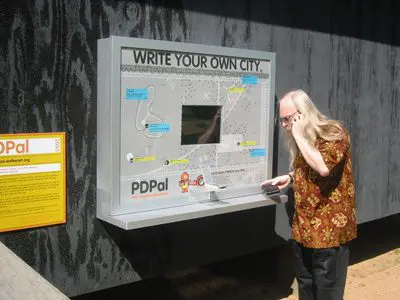

Commissioned by the Walker Art Center through its EAEM3 grant, a PDPal kiosk was installed in the Minneapolis Sculpture Park for Summer 2003. This and the following iterations did away with the application-generated pictograms, designing instead a complete cartographic system of ‘stickies,’ pictographic symbols, and parameters by which a user could map their own city, with or without the Cartesian grid. The kiosk contained a beam-able PDA application, through which users could map the sculpture park, and after hot syncing their PDA to their computer, could upload the data to a web site. The web site was more extensive, allowing users to map Minneapolis and parts of St. Paul.

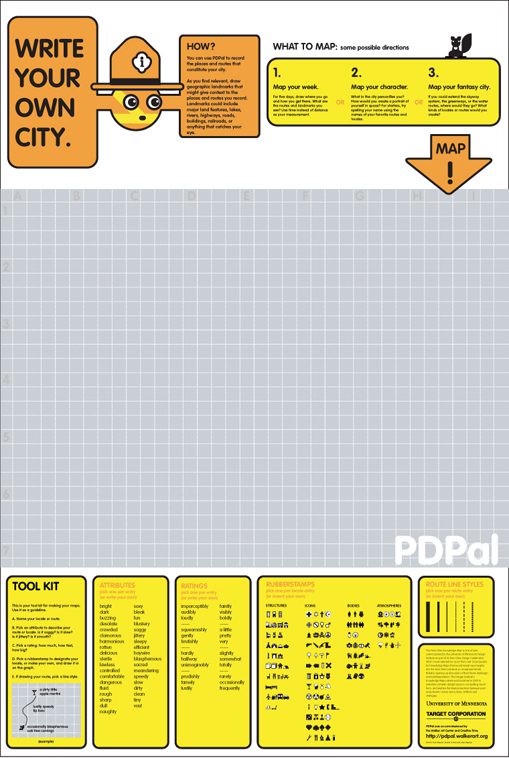

PDPal was part of the “Twin Cities Knowledge Maps” commissioned by the University of Minnesota Design Institute in 2003. Nine large interpretive maps were printed, offering views of Minneapolis/St. Paul on the themes of MOVING, WEARING, TELLING, RESTING, PLAYING, DWELLING, EATING, SHOPPING and MEETING. PDPal functioned as experimental documentary, using symbols and short anecdotes to reflect diverse daily paths through the metropolis. On the reverse side, a user could write their own city, using PDPal’s recording system and a set of pictographic stickers.

Commissioned by Creative Time in New York, PDPal appeared in Times Square in the Fall/Winter of 2003/2004. PDPal had three components:

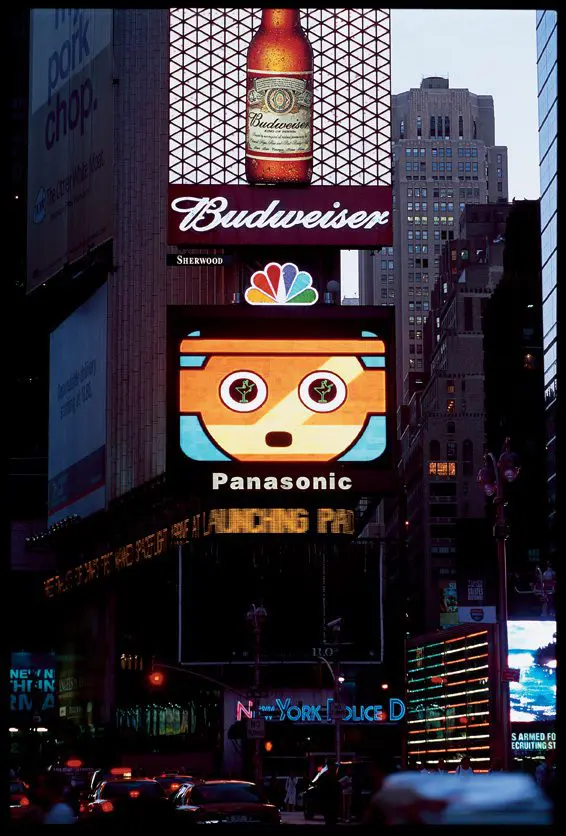

Once every hour, a 1-minute movie was broadcast on the Panasonic Astrovision board as part of Creative Time’s “59th Minute” series

Two kiosks, one stationary and one that moved monthly, were stationed in the Times Square area. Each kiosk contained a graphic of Times Square and a beaming box that contained the PDA application. Participants could beam the app to their PDA in order to map Times Square.

Two scheduled “walkabouts” were performed by the PDPal team, Creative Time, and participants. People convened at Chashama Theater in Times Square, broke up into teams, and carried out mapping missions in the area for an hour. we all then reconvened to share our map/narratives. Missions were either to be an alien anthropologist, carry out an algorithmic walk, or investigate a documentary aspect of the area. Glowlab participated in the first walkabout; click here for their report.

To describe space: to name it, to trace it…Space as inventory, space as invention.

Georges Perec, ‘Species of Spaces’

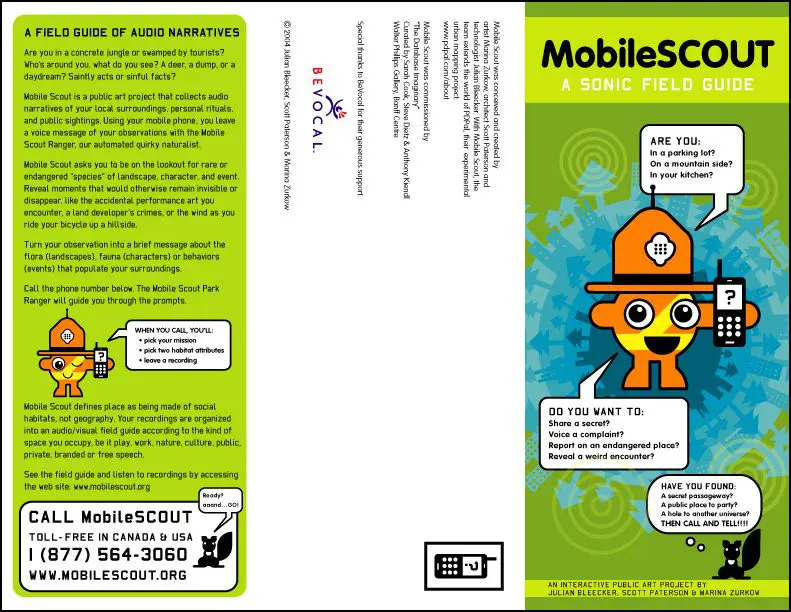

PDpal’s third iteration, called Mobile Scout, is an audio field guide, collecting phoned-in narratives of one’s local surroundings, personal rituals, and public sightings. Using your mobile phone, you leave a voice message of your observations with the Mobile Scout Ranger, our automated quirky naturalist.

Mobile Scout asks you to be on the lookout for rare or endangered ‘species’ of landscape, character, and event, revealing moments that would otherwise remain invisible or disappear, like the accidental performance art one encounters, a land developer’s crimes, or the wind as you ride your bicycle up a hillside.

Mobile Scout defines place as being made of social habitats, not geography. Your recordings are organized into an audio/visual field guide according to the kind of space you occupy, be it play, work, nature, culture, public, private, branded or free speech.Mobile Scout will be presented in the upcoming exhibition “Database Imaginary” curated by Steve Dietz, Sarah Cook and Anthony Kiendl. Originating at the Walter Philips Gallery at the Banff Centre, Alberta, Canada, the exhibit will tour Canada and Europe in 2005-06.

PRESS

-> click here for 2003 press in .pdf format

-> click here for article by cartographer and professor Denis Wood in .pdf format

DOCUMENTATION

-> click here for eyebeam atelier installation documentation

-> click here for Walker Art Center installation documentation

-> click here for The U of Minnesota’s Design Institute “Knowlege Map” documentation

-> click here for Creative Time installation documentation

-> click here for various PDPal swag documentation

ARTIST BIOS

PDPal represents a synthesis of three individual artists’ interests. Scott Paterson explores architecture as an interface protocol between the activity of our daily lives and the space of digital networks. Marina Zurkow addresses the characteristic aspects of PDPal, as well as the narrative direction embedded in a map-making project. Julian Bleecker is drawn to the project by his continuing study of the ways technology can create an engaged critical consciousness about culture. Parsons School of Design MFA DT students Shruti Chandra, Vicoria Fang, Fang Yu Lin, Jen Wheatley, and Austin Chang were part of a research fellowship that ran from Jan 1- June 15, 2003.Julian Bleecker has been involved in technology design, the development of mobile and networked technology systems, and scholarly work studying the mechanisms by which technology design and innovation occurs.

Currently, his interests are focused on exploring the relationships between place and social engagement through the use of 802.11 ‘WiFi’ technology. WiFi.Bedouin is a mobile, portable WiFi node that serves as a wireless communications node, allowing one to have a personal web server disconnected from the public Internet. WiFi.ArtCache is a WiFi-based repository of smart art objects that users can download to their WiFi-enabled laptops. WiFiKu is a project that constructs interpretive maps representing urban neighborhoods based on Haiku constructed from the names of WiFi nodes in those neighborhoods. NetMagnet is a spatial networking experiment that performs file-swapping amongst computers that are physically proximate. He recently collaborated with Marina Zurkow and Scott Paterson on PDPal, a Palm-based art-technology project, which received the Emerging Artist, Emergent Media Grant from the Walker Art Center. He has been granted art-technology residencies at Eyebeam Atelier, the Banff Center for the Arts, and has had projects shown at the American Museum of the Moving Image, Bitforms Gallery, Art Interactive, and Times Square.

He has a Bachelor’s Degree in Electrical Engineering, a Master’s Degree in Computer-Human Interaction, and a Ph.D. from the UC Santa Cruz’s History of Consciousness Board where his dissertation is on technology, culture and entertainment. He is an Assistant Professor in the Interactive Media Division and Critical Studies Department of the School of Cinema-TV at the University of Southern California.

Scott Paterson is a practicing information architect and interaction designer in New York. He teaches Interface Design, Multimedia Studio and Thesis Studio in the MFA in Design and Technology Program at Parsons. He also has taught a course, Interfaces for Public Space, at Columbia Graduate School of Architecture. His education includes a Bachelor of Architecture degree from University of Minnesota CALA and a Masters from Columbia University GSAP.

After working as an architect for six years in New York, he joined Plumb Design (www.plumbdesign.com) as a site developer and forged his own position ’ a liaison between design and technology departments ’ as a technical producer. Independent work since leaving Plumb Design explores architecture as an interface protocol between the activity of our daily lives and the space of the network. Recent projects include PDPal (www.pdpal.com) a mobile-based storytelling project that has exhibited internationally, a wireless PDA interactive examining the potential overlaps between networks of streets and mobile devices, and a public curatorial environment for Mass MoCA. He has received grants from the Walker Art Center, Parsons School of Design and The Design Institute at the University of Minnesota. Scott is an active member of the new media art community including Rhizome.org and Mindspace.net, he lectures internationally and his work has been exhibited in Amsterdam, Berlin, Florence, Mexico City, New York and at the Banff Centre for the Arts.

Marina Zurkow is a multidisciplinary artist who works with character, icon, and narrative in several forms: animated works, interactive installations, and material goods.

In 2004, Zurkow completed a seven channel, multi-linear animated installation, ‘Nicking the Never,’ which was first presented as a work-in-progress at The Kitchen in New York, May 2004.

Other recent projects include the award-winning animated episodic ‘Braingirl,’ that chronicles a mutant-cute girl who wears her insides on the outside; ‘PDPal,’ a mapping application/ installation for screen, web and mobile devices that allows a user to ‘write her own city,’ in collaboration with architect Scott Paterson and technologist Julian Bleecker; and ‘Pussy Weevil, or How I Learned to Love the War,’ a vile, interactive, animated persona. Zurkow’s icons and characters have been incorporated into diverse projects, from animated films to hotel design, lightboxes and clothing.

Zurkow’s work has been exhibited at the Sundance Film Festival, the Rotterdam Film Festival, Ars Electronica, the Walker Art Center, the Brooklyn Museum, SFMoMA, Eyebeam Atelier, Totem Design and bitforms gallery, and broadcast on MTV and PBS. Zurkow was a 2003 Rockefeller New Media Fellow, and received grants in 2001-2002 from Creative Capital Foundation, the Jerome Foundation and the Walker Art Center. She is an adjunct professor at Parsons School of Design in the MFA Design & Technology Department.

After attending Barnard College, Zurkow received a BFA with honors in Fine Art from the School of Visual Arts, where she also received the Silas Rhodes Award for Outstanding Achievement. She was born in New York City and resides in Brooklyn.

©2002-2025 Bleecker, Paterson and Zurkow

https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2011/talktome/objects/140008/

http://gallery9.walkerart.org/bookmark.html?id=624&type=text&bookmark=1

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/pdpal/

www.wired.com /2003/10/stroll-down-memory-lane-with-pda/

Stroll Down Memory Lane, With PDA

Erik Baard 4-5 minutes 10/10/2003

NEW YORK — A new Times Square art project lets people map their insider knowledge, memories and ideas about city landmarks with their PDAs and share those anecdotes online. Just don’t confuse the project with the Zagat Survey — you might get lost in a thicket of strangers’ nostalgia.

Through Dec. 12, people wandering Times Square can wirelessly download a program called Personal Digital Pal, or PDPal, at a kiosk “beaming station” on 42nd Street. Once the program is loaded, users can record their wanderings by sketching the paths they took and writing commentary about the places they visited. When they get to a laptop or desktop computer, they pour all of this into a central website so others can appreciate myriad overlapping perspectives about the same sites.

“People using this will be like squirrels gathering nuts and bringing them back to the tree,” said technologist Julian Bleecker, who created the project with Scott Paterson, an architect and artist, and artist Marina Zurkow. Adam Chapman, an artist and programmer, aided with PDPal’s implementation.

“We want people to use their PDAs to harvest experiences and create another communal sense of the city,” Bleecker said. “The initial program download is available through the kiosks, rather than online, because it forces people to go to this physical space to get started and have these experiences. Times Square may be the most tactile, vibrating and resonant place in the world.”

This might sound like the vision some had of all places getting tagged with information by their GPS coordinates, but the artists decided not to use that technology. This was because of its relative scarcity and the difficulty of getting reception in Manhattan’s canyons of concrete, glass and steel. The artists’ decision was also an aesthetic choice.

“We wanted a more poetic application, rather than something so Cartesian,” said Paterson. “People don’t feel urban places in terms of longitude and latitude. One thing a lot of people talk about is the video arcades that used to be here, but they don’t necessarily remember exactly where they were.”

Times Square has been revitalized in recent years. New construction and a whitewash by New York’s city hall replaced strip clubs and seedy bars with flashy retailers and street-level TV studios. Even landmarks aren’t as immutable as they might appear: The Empire Theater on 42nd Street, known as the Eltinge Theatre when it opened in 1912, was lifted and slid on rollers 170 feet to the west in 1998.

Strollers through Times Square will be reminded once an hour to participate in PDPal by an animated mascot on the huge Panasonic screen at the south end of the crossroads. Panasonic is sponsoring PDPal along with Creative Time, a group that fosters convergences between arts and technology. An earlier incarnation of the program debuted at the sculpture garden of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

PDPal is part of a new technology thrust for the district, said Times Square Business Improvement District President Tim Tompkins. “For a hundred years, Times Square has been a showcase for huge-scale display technologies, but these kinds of micro-scale technologies have only been in people’s pockets for 10 years,” he said.

Tompkins said he would love to meet with technologists and artists to find more ways to use cell phones, PDAs or other devices to guide tourists through the neighborhood and give them a glimpse of the place’s history. “I would also love to see how these devices could be used for interactive functions with the mega-signs,” he said.

That mainstream vision of Times Square as a canvas of lights, however, drives home the artists’ point. Zurkow said that before working on PDPal she remembered Times Square as a “place to get fake IDs” when she was a teenager. And the project would have been just as exciting in lesser-known neighborhoods, she said.

“Times Square is where so many issues are concatenated, but to think to say that one neighborhood represents New York City more than any other is anathema to the project.”

Steve Dietz: You specifically refer to PDPal as a public art project. What does this reference beyond the fact that there is a potentially wide public? Julian Bleecker: PDPal is public in many senses. The more obvious aspects of its public nature are that there are channels of participation that invite active engagement by a large audience. The web is one channel, PDAs another. PDPal is also public in that its “subject”—those things with which its audience engages—is, generally speaking, places in publicly accessible physical locations that can be experienced in some fashion by visiting that place. A more interesting way in which PDPal is public is the way it allows one to share the experiences of these places. One can filter the maps PDPal creates by looking at those of particular users; everyone’s maps are available for anyone to view. This is perhaps the most evocative aspect of PDPal’s “public” qualities.

Scott Paterson: I tend to think of the term public as a spatiotemporal phenomenon. It concerns the experience of collectively constructing zones where we then act out roles as citizens of that public. PDPal is a public art project because it provides two platforms that support the collective construction of these citizen zones. Inspired by psychogeography, cognitive mapping, and Hakim Bey’s temporary autonomous zones, PDPal investigates methods of construction via dimensions beyond the latitude and longitude of geographic mapping, such as time, memory, and emotion. PDPal exists as a public art project in that it considers mobile devices and the web as constantly shifting ephemeral public spaces generated by the expressions of its population of users—a place we call the “communicity.”

Marina Zurkow: By public art, I mean it’s a project that is shared by many people in a public forum, open for others to witness and/or participate. It is public in the way it is disseminated, through kiosks both within institutions but also in the street, via beaming stations and free exchange between users’ infrared ports. I am not forgetting that it is not public for everyone (is any art?); you need techno-literacy and techno-access to participate. But it is not a piece to own or consume.

SD: Why did each of you first become interested in the idea of doing a mapping project?

JB: My interest in PDPal as a mapping project continues to be around the possibility of some sort of cartographic mapping of experience. I’m excited by the idea of maps that are able to refashion traditional boundaries of space—flexing political, economic, and even natural borders and instead bounding space along another entire schema of attributes. With PDPal, one can assign to places attributes and ratings, such as “frequently desolate.” What does New York City look like when such descriptions as these are mapped, and when the boundaries are between, say, blasphemous and dangerous zones, rather than two police precincts or the eastern side of a park?

SP: Having an architecture background, I’ve been making work that seeks the possibility for “architecture” as a protocol between the virtual and the real, that is an interface between the activity of our daily lives and the space of the internet. If we think of physical architecture as a social construct between our bodies and our world, we can also think of a dynamic architecture of information through which we can inhabit and demarcate place within any networked environment—such as the internet. Inherent to this type of work is the mapping of inputs to outputs. In this case the mapping is a kind of translation, an algorithm, an architecture.

MZ: I was first interested in doing a beaming wireless application that utilized character and explored a bridge space between the real and the imagined. This space was one I always perceived as being enriching narratively to both respective spaces, each bouncing off of and informing the other. Scott and I converged in our very different ideas about space and experience design, as I think very narratively (albeit as [I am] an experimental narrative maker, that thinking hinges on structure and arc, not on traditional unfolding of plot and conflict).

SD: Is the communicity a utopian notion or another form of data mining?

SP: I’d say it’s neither utopian, for the simple reason that we’ve not dictated the ideal goal, nor data mining, in that the input/output structure is open ended. Our role as artists in this project has been as frame makers. We’ve often discussed the spectrum between work that asserts and work that frames. PDPal provides a provocative frame through which users assert. If we now speak about what constitutes the identity of a place as opposed to space, we get into issues of the criteria for description. We can begin by talking about our senses—touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste—but we can also talk about memory, exposure, connectedness, duration, all of which deal with time. If city building codes are legislation written by elected politicians, PDPal, for me, is a collaborative architecture that exists in a series of ongoing feedback loops.

MZ: The more that the project is framed through the use of instruction sets and specific “assignments” (as in a classroom context), the more the communicity has viable play and doesn’t simply call data mining by a glorified name. Currently, the communicity aspect of the piece is little more than simple data mining. But there are two ways in which we see growing communicities. The first is geographically based but very specifically framed. I wouldn’t call it utopian as much as eye-opening to the ways in which the city can be used, transformed, and examined. For instance, a communicity of anarchist users will have a version of the city that is meaningful to them: sharing locales, sharing impressions, and uses of space that are meaningful to a group at large—a group that may or may not know each other outside the virtual environment. A classroom of students could build overlapping cities that reflect their critiques of the present city configurations. Another user group might find the community to be the equivalent of a menagerie of transformed fantastic city parts, together making this beast that is the city in all its raging glory and dynamism. The second way in which we perceive the communicity is more like a utopian architecture project, and something Scott can address better than either Julian or I can, having to do with refigured space based on shared dynamic properties, confluences of data, and artistic reinterpretations of users’ flows (check me, Scott!). It’s a revisualization project that is really off the Cartesian x/y grid.

SD: Describe each of your roles in the collaborative process—both functionally and psychologically.

JB: Functionally, we were all actively engaged in the conceptual work that went into the project. We spent many, many hours hashing through the project’s motivation and what sort of meaning-making apparatus we wanted it to become. After the project had some conceptual underpinning, we became specialists. My role was the technologist, which meant that I did much of the general architecture of the “guts” of the PDPal system and, even more practically, did the programming for the PalmTM application and the middleware that constitutes what we refer to as the PDPal mothership—the online part of the application. I also worked closely with a really valiant and diligent team of researchers from Parsons [School of Design] who built the Flash application that is the front end to the web application: Austin Chang, Shruti Chandra, Vicky Fang, Frank Lin, and Jennifer Wheatley.

SP: Functionally I have been responsible for interface design, interaction design, and some production management of the website. I find I am often the linguistic glue between Marina and Julian because I have both a design and technical background. This has been interesting because I have to take into account both of their expertise in designing the interface and interactions. Marina and I work together on making sure the front-end design is consistent with the project goals and I work with Julian to make sure the schematics I’ve made are doable as well as meaningful. Through it all we developed some interesting working jargon so we had a check that we were all on the same page.

MZ: As Julian said, we all developed the project conceptually. This meant sitting around for hours fighting about how far out you can go with calling something a map, and what is feasible in software development on a relatively small scale for minimalist platforms like the PDA. Functionally, I am the character developer. I designed the Urban Park Ranger and although we all contribute to and critique its manifestation, I am responsible for its realization. I also do all the motion graphics for the project (intros, trailers, etc.) and all the spin-off (be that T-shirts or an analog version of the project). I also spearhead giving voice to the project, though Scott’s been instrumental in contributing provocative language to the instruction sets and the phrasing of any textual components.

SD: I think the cartographic aspect of PDPal and its genealogy with the Situationists is clear, but I’m interested in how you think about the narrative/character aspect of the project. What is the role of the Urban Park Ranger beyond a help function?

SP: Every project has a voice or bias. It’s the artist’s prerogative to make this voice explicit or implicit. Much software-as-art work being done today has an implicit voice in the protocols inherent in the interaction, which is not readily apparent because the project is seen as enabling action rather than limiting it. The Urban Park Ranger on the contrary acts as a provocateur as well as a host to explain the particular bias of the software and in doing so inform the user of our critique of more traditional mapping techniques.

MZ: The world may be divided—somewhat unequally, I suspect—between those who need an anthropomorphic conduit and those who want their material straight up. I’m in the former camp most of the time. It’s been our hope that this character gives tone to the piece—a playful stance—and through its characterization as a park ranger/crossing guard, a sense that this “city” we’re trying to forge is populated. In addition, the character, by being developed as a system of malleable and morphing parts, suggests the flexibility of all of the parts within the established system of PDPal.

SD: Last question—three parts. I think one of the big issues with open systems is how to design a framework, as you put it, that is open enough to the spontaneous emergence of communicities but also encourages “good” input. What have you learned from the initial implementation at the Walker Art Center and what are you changing for the Times Square launch?

JB: I learned that there is a profound deficit that arises when attempting to simultaneously strive for technical and creative sophistication when one’s resources are constrained. Conceptually the project is rather sophisticated and I am afraid that way we caught ourselves in a bit of a language sinkhole. I describe the project to friends and colleagues using the various idioms we’ve crafted over the last 18 months—“locale,” “attribute,” “route”—all supernaturalized amongst “we,” but quite fast-and-loose when it comes to trying to give an elevator pitch to even clever folks. There’s constantly this “What is PDPal?” question, and it’s not meant to be a set-up question that one gives for the purposes of an interview. It’s a real question, and you can see the earnestness in people’s faces because they want to know what we’ve been spending so much time on. I’m hoping the changes we’re making to the Times Square evolution of PDPal—the ability to create a more literally connected dialogue amongst users, as well as the commissioning of PDPal maps of Times Square that are historically, culturally, geographically specific and that mark the many facets of Times Square in authored ways—will bring us to the point where that earnestness for an understanding of PDPal is satisfied.

SP: First, that it’s difficult to even overcome the perception of the PDA as a productivity device and, second, to transform it into a creative tool. We had to spend a good deal of time simply explaining how to use the PDA interface, let alone the PDPal interface. In the face of tabul(et)a rasa, most users froze up creatively. When given a very specific assignment, however, they more quickly generated a framework for remembering the basic functions, and when challenged by a specific point of view (e.g., the Urban Park Ranger), users had immediate entry into their own imaginative voice. For Times Square we have three directives to begin the experience. The directives grew out of research about Times Square’s past, present, and future. We plan to have mapping workshops with the various populations that inhabit Times Square during the run of the installation as well as invite a series of guest map makers as a catalyst for discussion. Lastly, we added a feature to allow users to comment on each other’s recordings, thus increasing dialogue and community.

MZ: I’d add that the directives we came up with—three questions—are distilled from thinking about the different ways a user interacts with a city: through time, movement, consumption, fantasy, memory, and projection. The questions we chose specifically for Times Square ask users to consider what and how they consume a place; what they remember and project; and what sort of transformative fantasies they have about the present—in other words, how they characterize that space.

The other thing we learned is that we no longer give total primacy to the software version of PDPal. We have made a one-minute film and several print versions of the project, having developed a core visual language that allows us to express it in a variety of forms, from the overtly interactive to the contemplative.

Use the Contact Form below to discuss how you can engage Near Future Laboratory to help you make sense of your organization's possible futures.