Project Summary

Imagining a future of self-driving cars using the humble quick-start guide as a container of the implications and contingencies of the autonomous way of life.

Project Semantic Tags

ARCHETYPEAUTONOMOUS VEHICLESDESIGN FICTIONFACILITATIONFUTURE OF XINTERACTION DESIGNWORKSHOP

The Outcomes

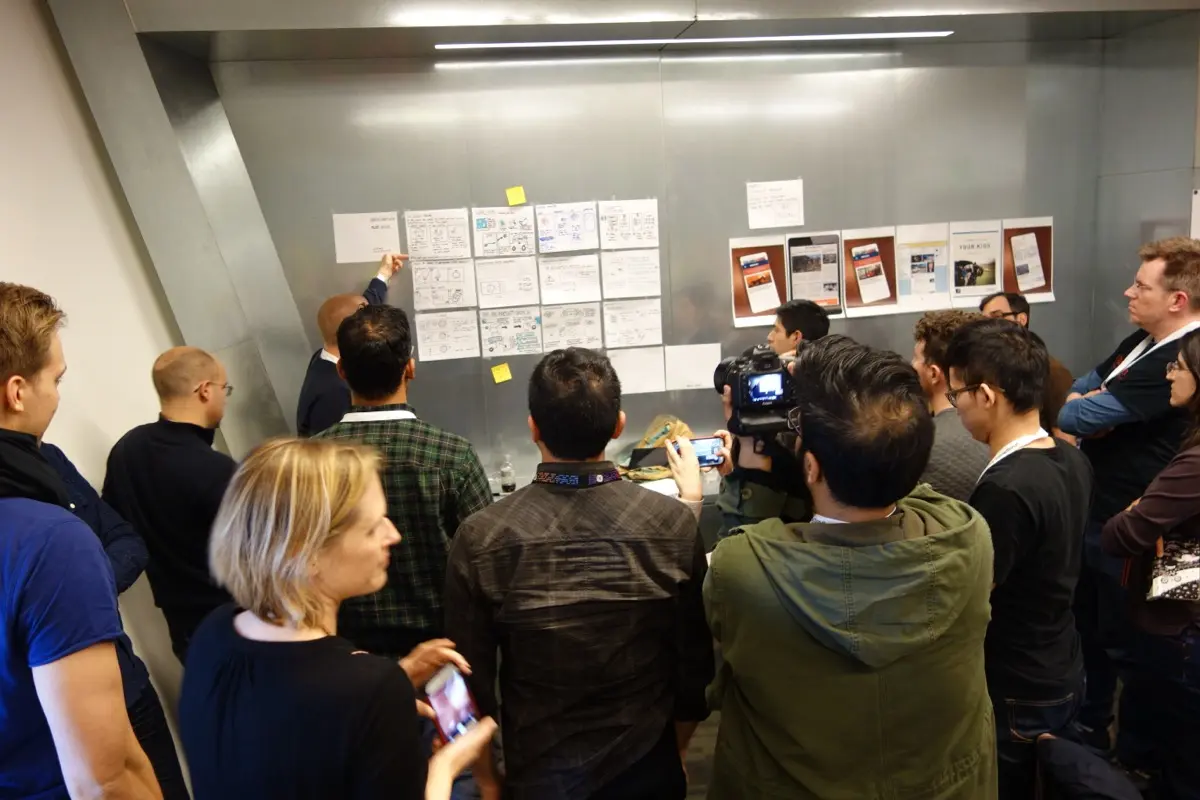

The workshop provided a hands-on introduction to Design Fiction and its methodologies and principles within a professional learning and development context. This workshop was conducted at a time when Design Fiction was still a naescent concept, while many engaged interaction design and user-interface design professionals were focussed on legacy approaches and practices.\n The feedback from participants were positive. Many participants began to integrate the principples and value of Design Fiction into their own organizations. The PDF of the Quick-Start Guide continues to be one of the most downloaded artifacts on the Near Future Laboratory Shop of Futures Artifacts.

The interaction design for a self-driving car

By all accounts, the self-driving vehicle, unlike the personal jetpack, will come to a salesroom near you sometime in the near future. When an idea moves from speculation to designed product the work necessary to bring it into the world means that it is necessary to consider the many, many facets of its existence — the who, what, how, when, why’s of the self-driving car.

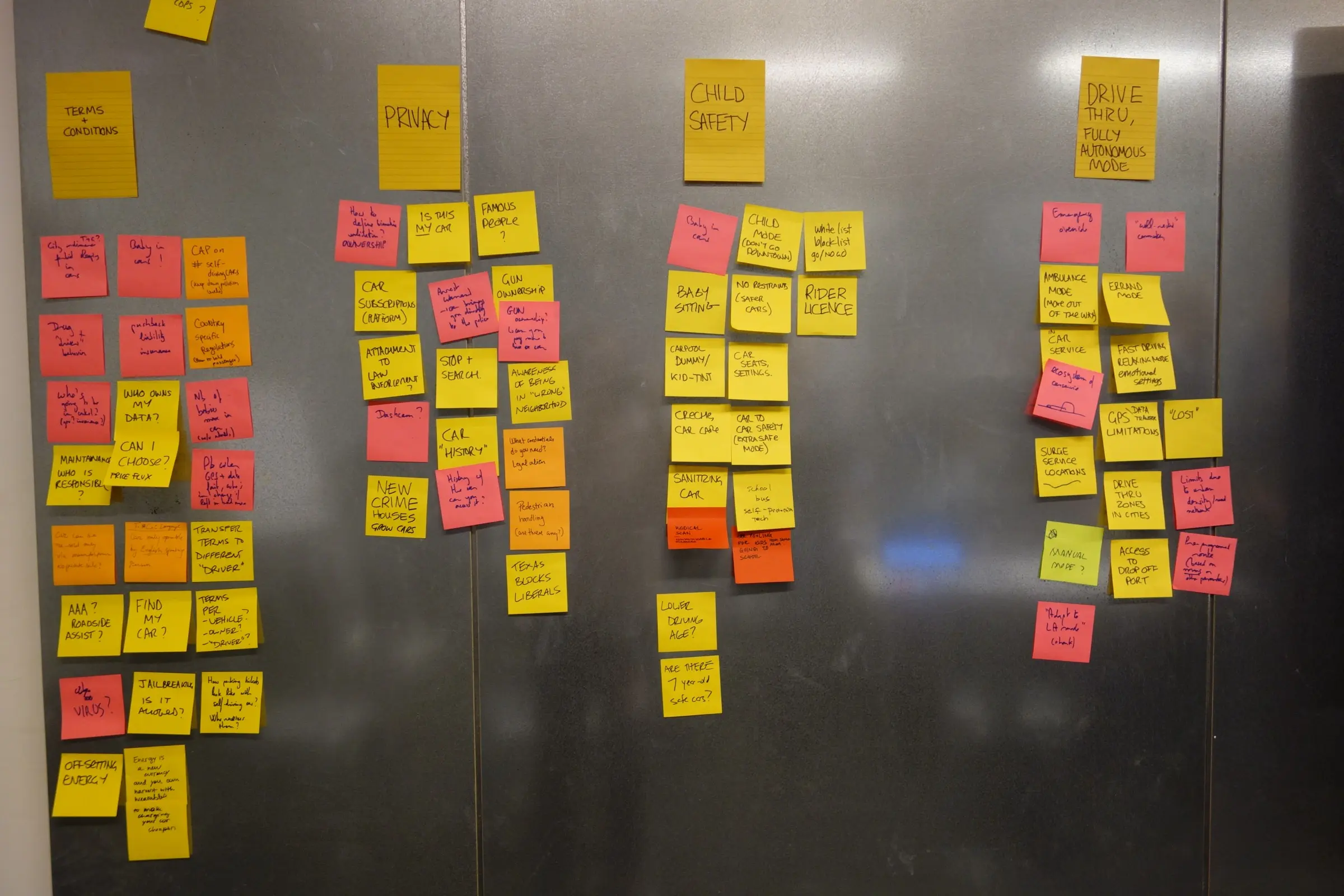

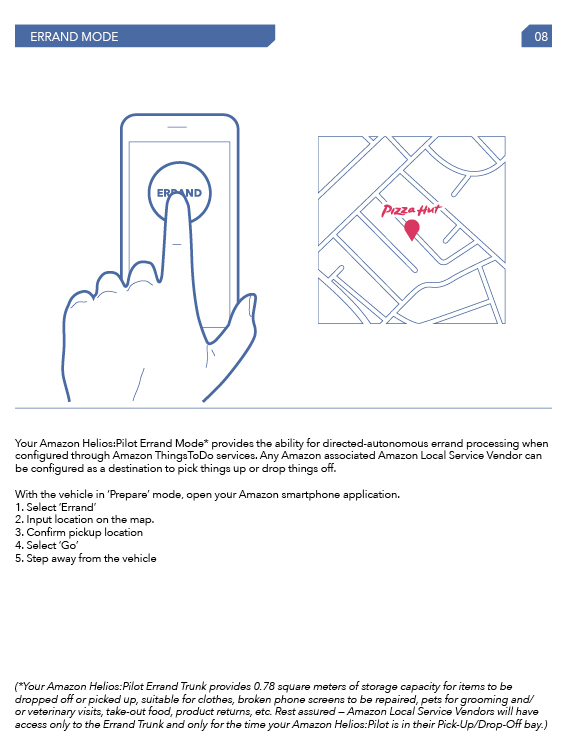

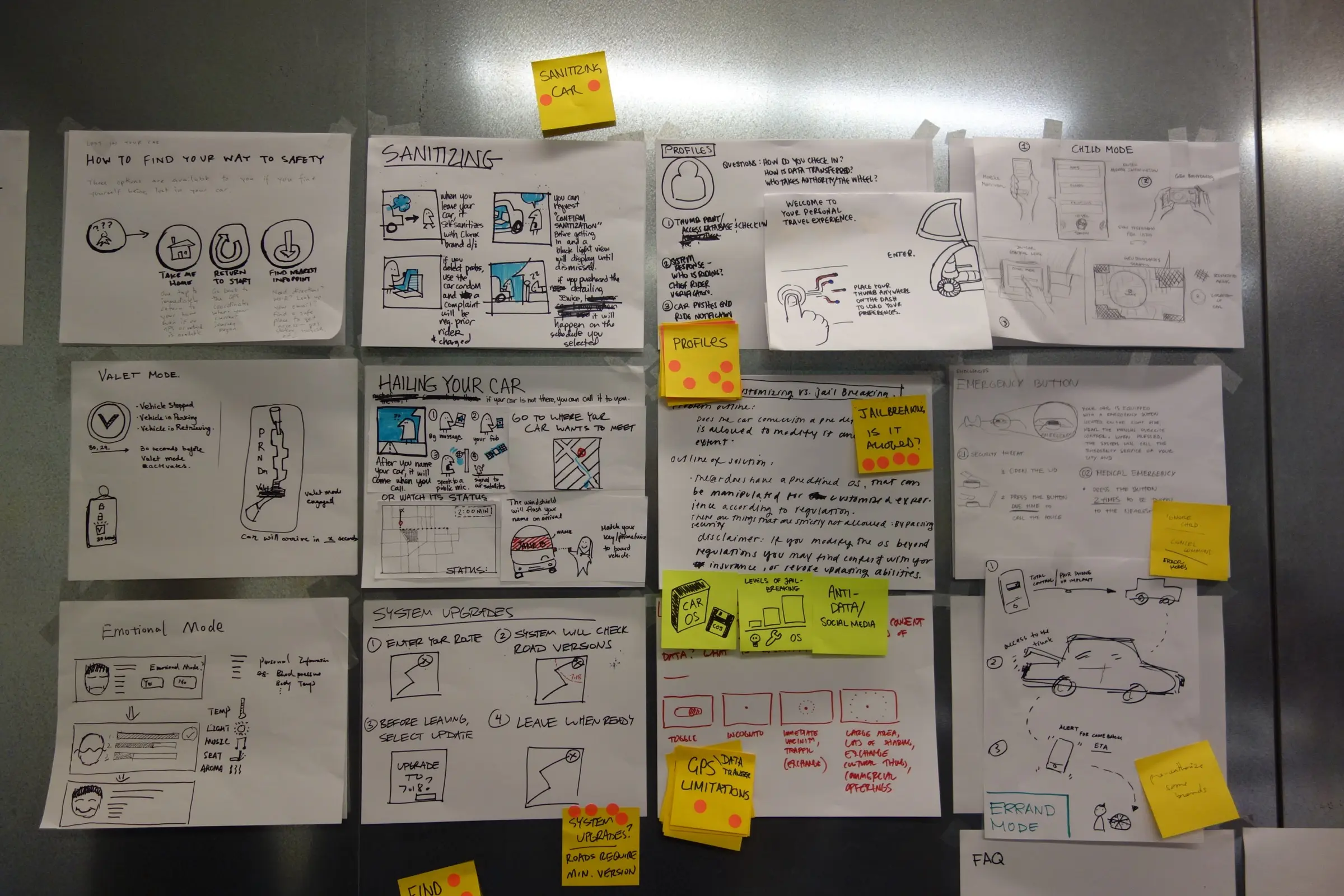

It’s easy to speculate about the self-driving car. But, touch on the topic of allowing one’s self-driving car to be used in the Uber network of modern-day taxis immediately begs the question — what do you do if you forget a bag of groceries after sending it into Uber mode? Will there be a geo-fencing mechanisms to control where the car goes — and how fast it goes — when you give the “keys” to your teenage son to take to football practice. How does the car pickup groceries — and how do you upload the list — when you send it on errands?

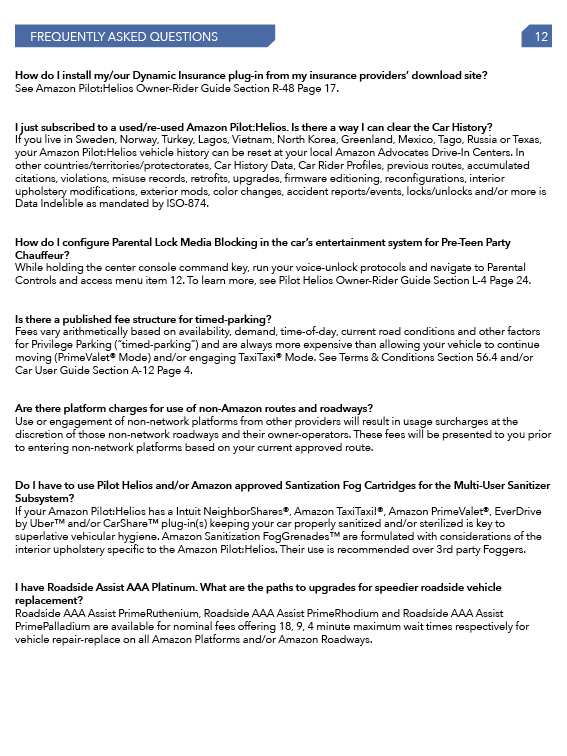

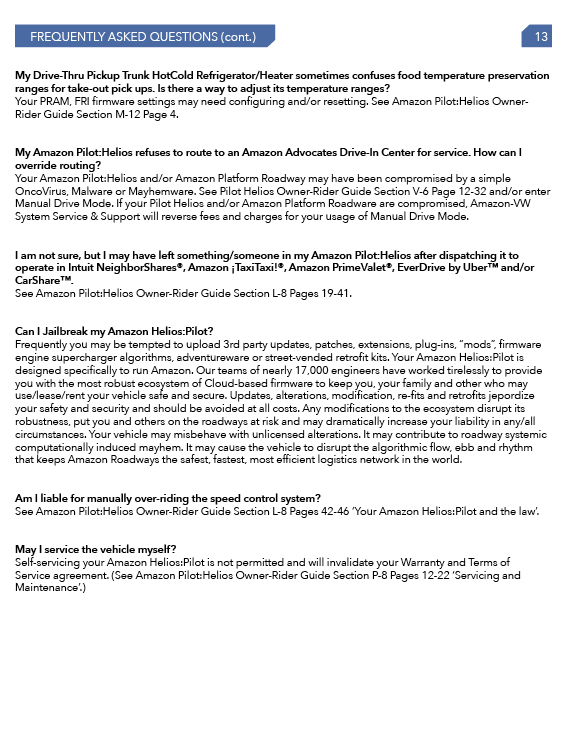

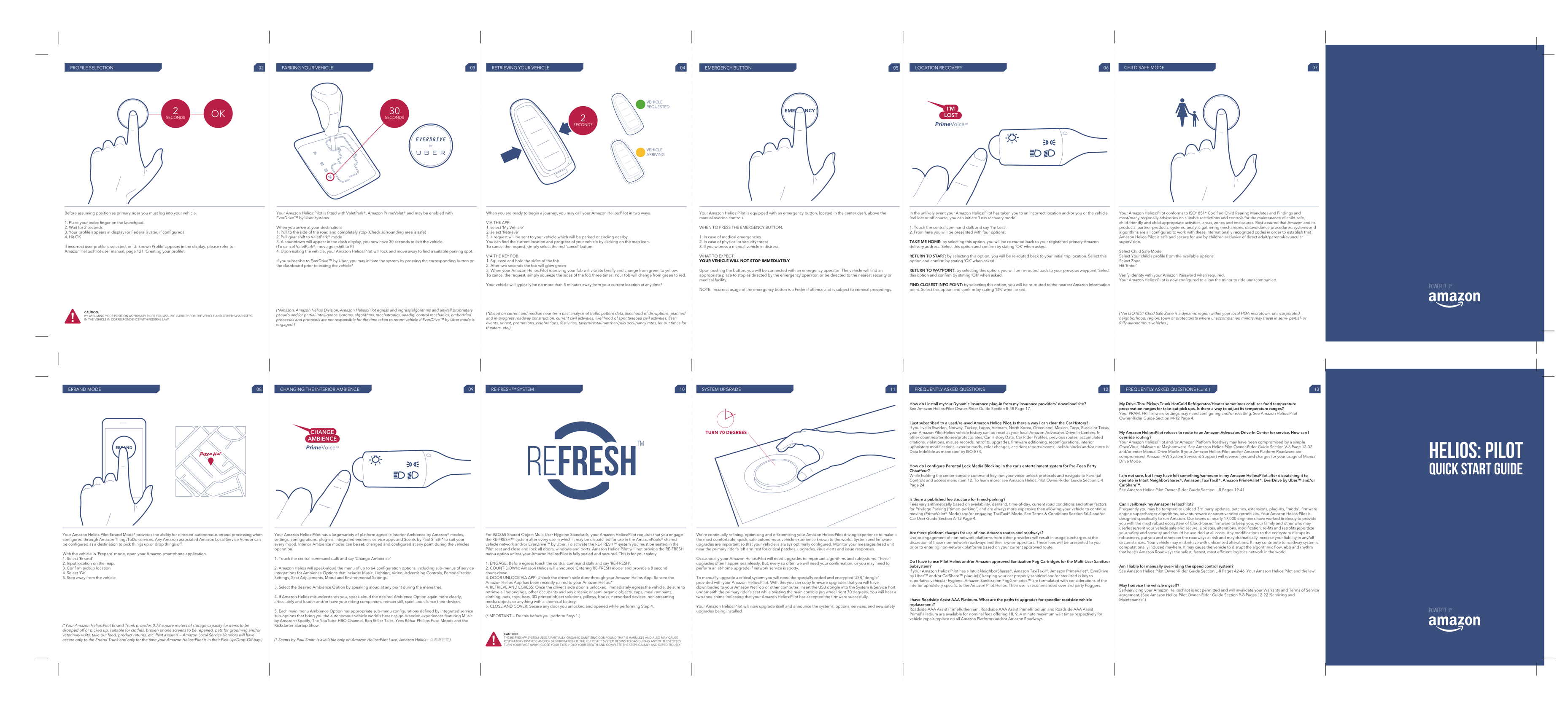

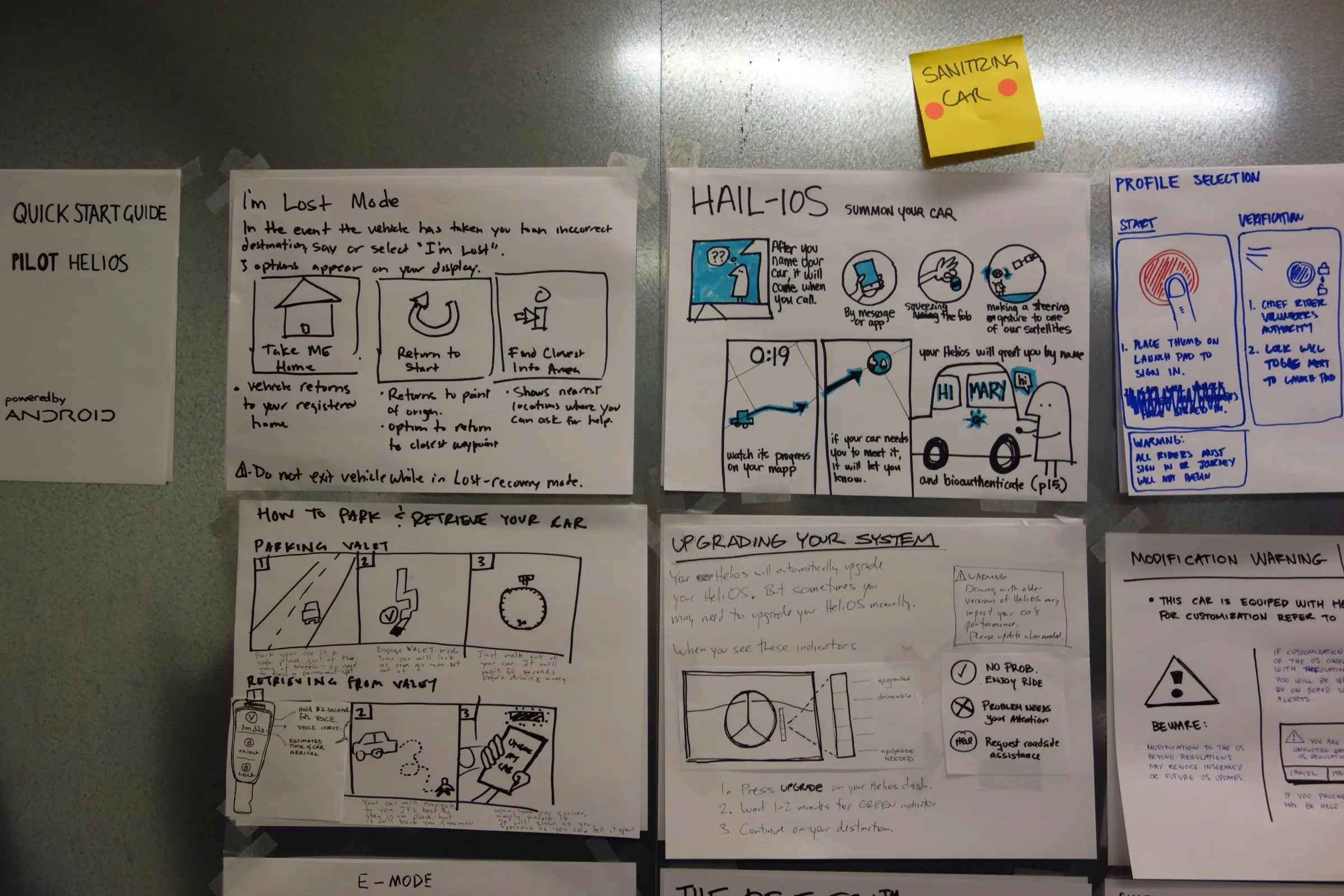

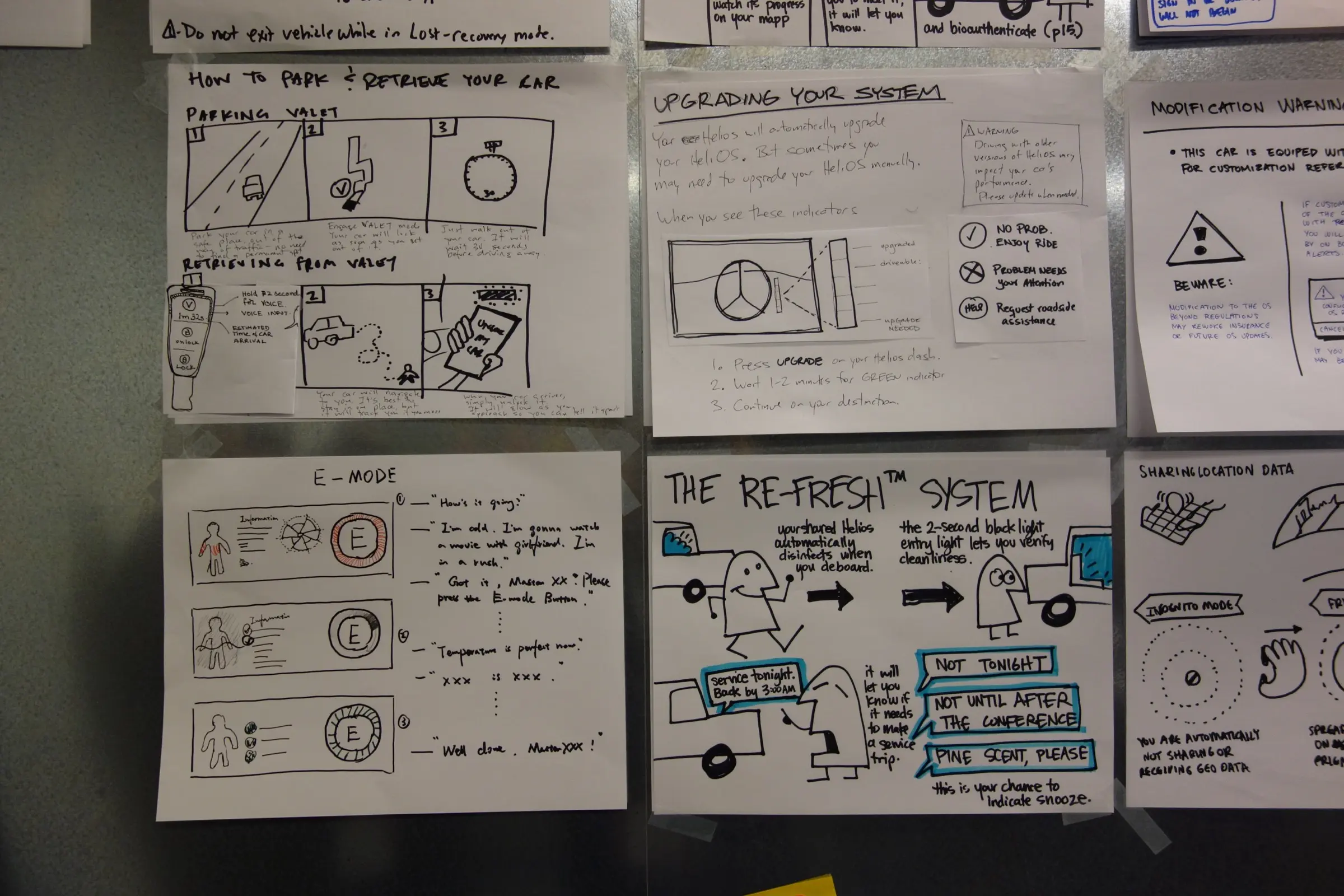

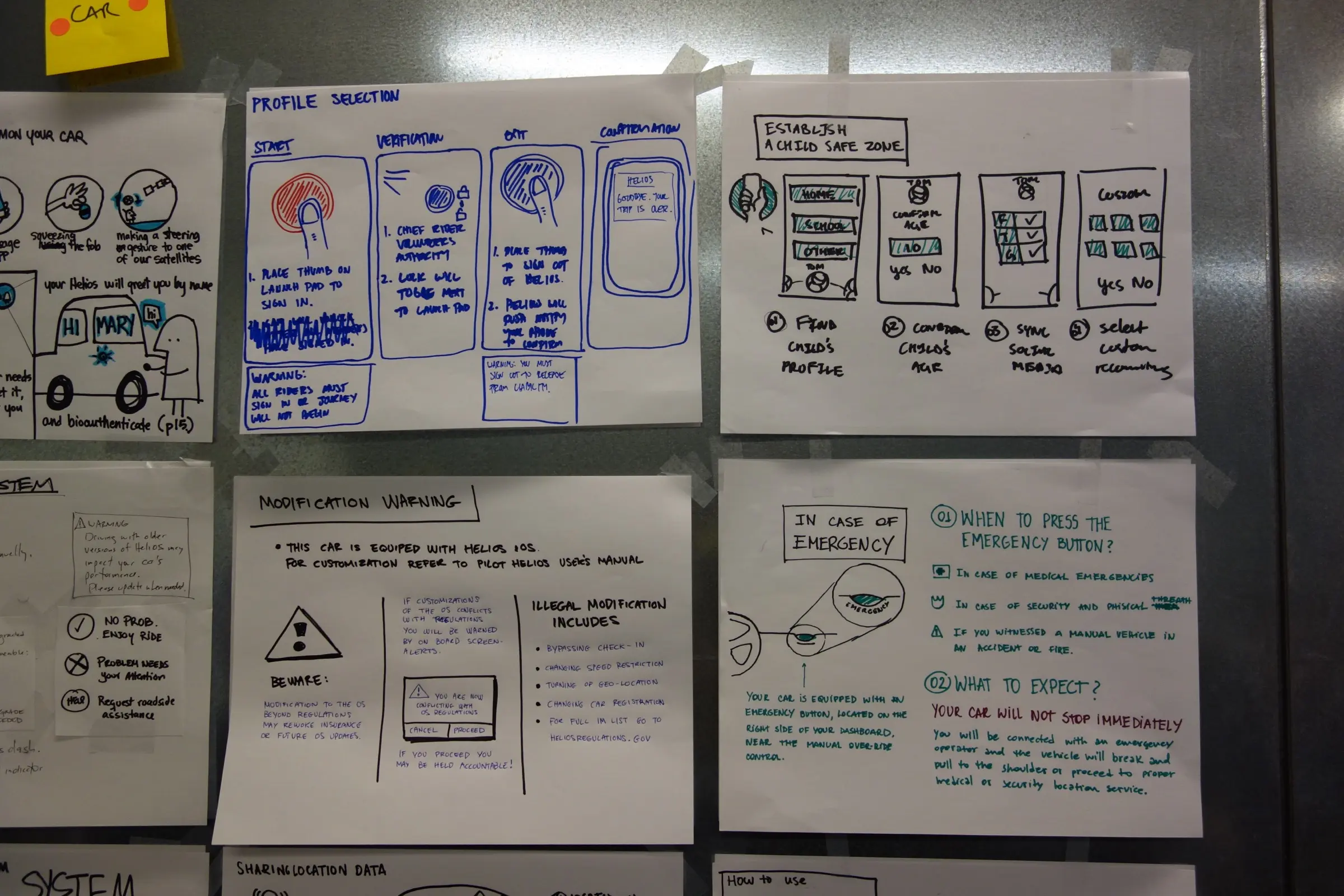

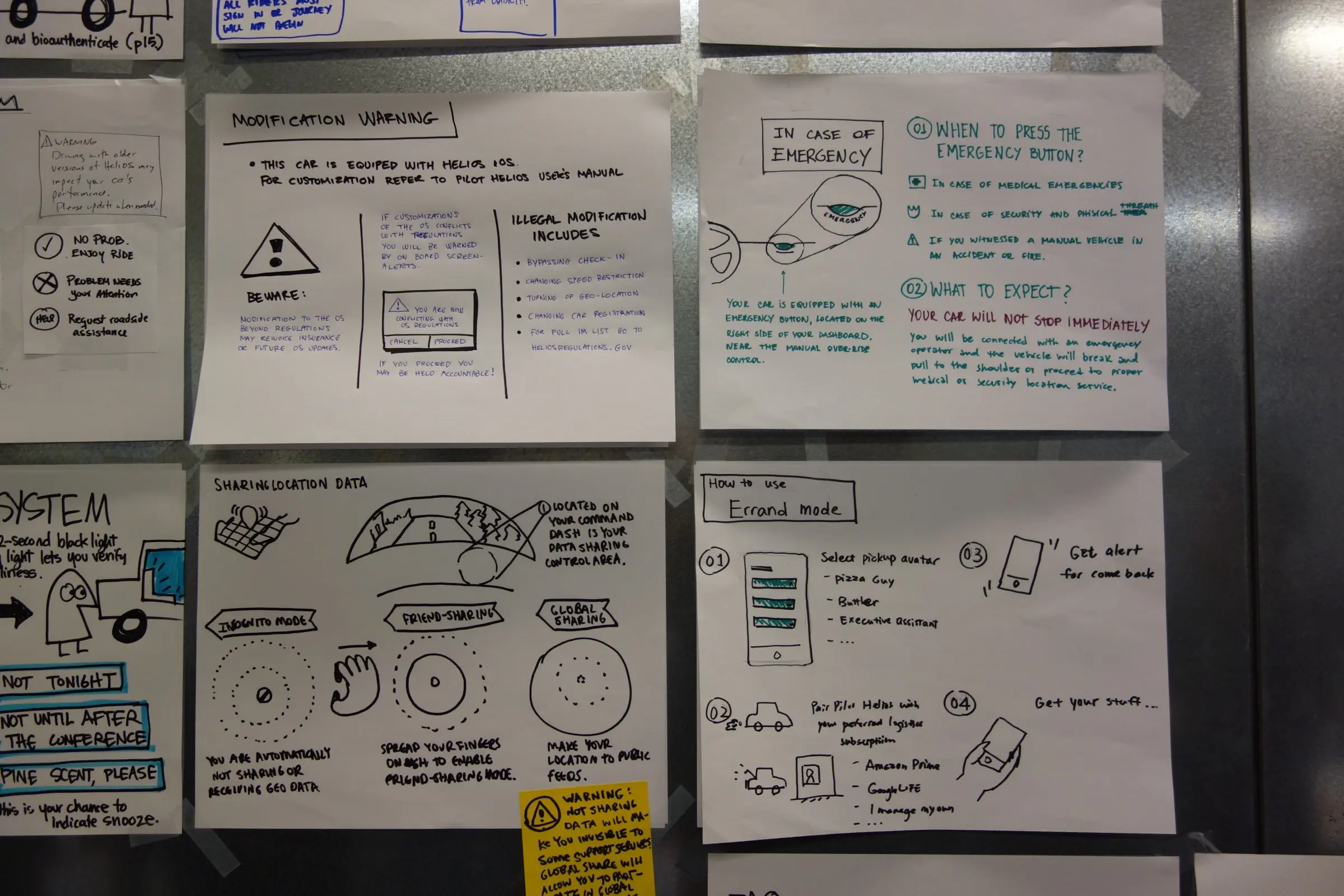

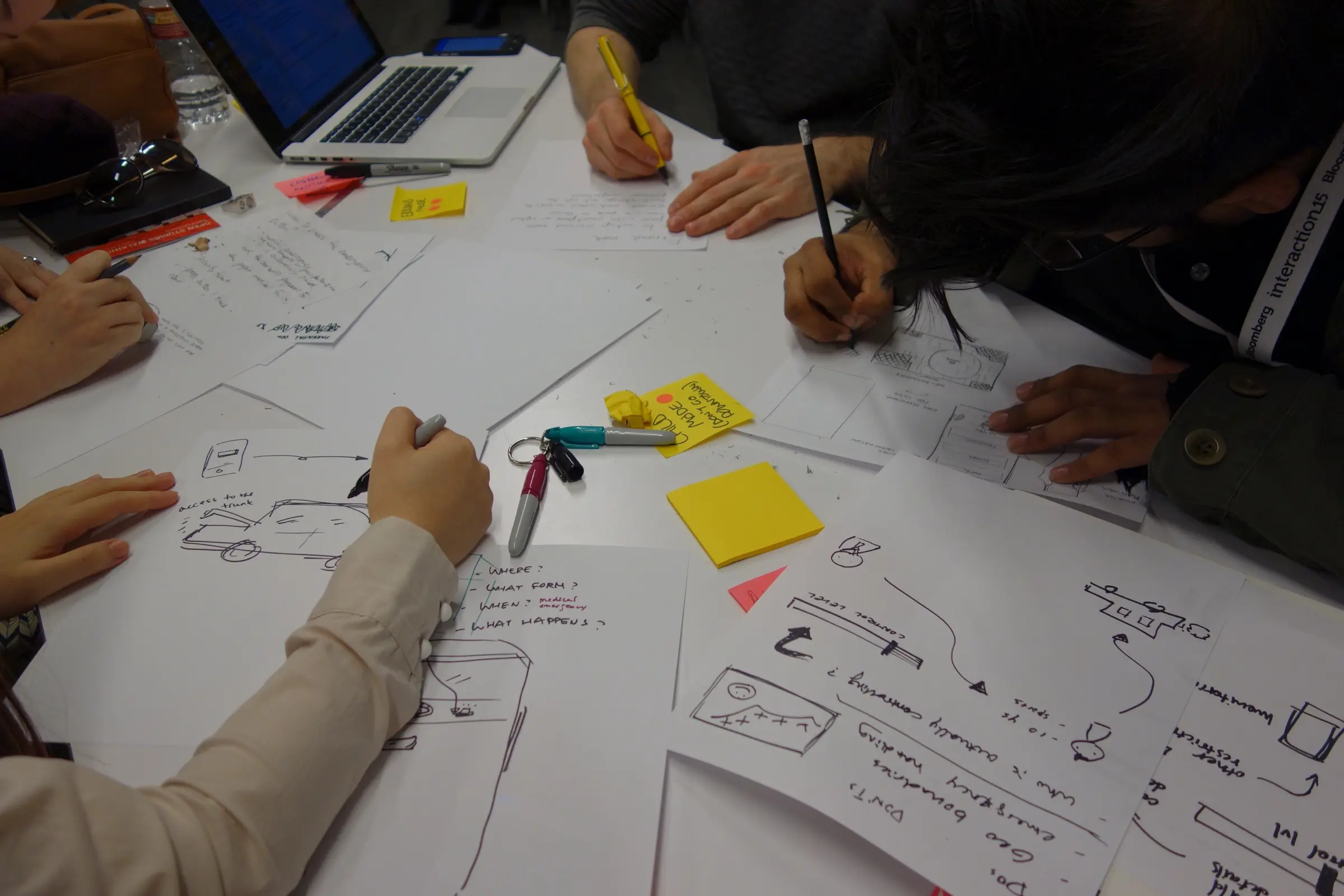

To spark a conversation around the larger questions regarding a world of autonomous vehicles, we set about to create a tangible artifact from the near future of the self-driving car. We ran a workshop at IxDA 2015 in collaboration with students from the CCA and conference participants to create the interaction design for a self-driving car. We did this as a way of digging into the details, discussing the known topics and raising many more unknown ones. Our design brief: Represent the features, attributes, characteristics and behaviors of the self-driving car and its requisite “ecosystems” through the vehicle’s Quick Start Guide.

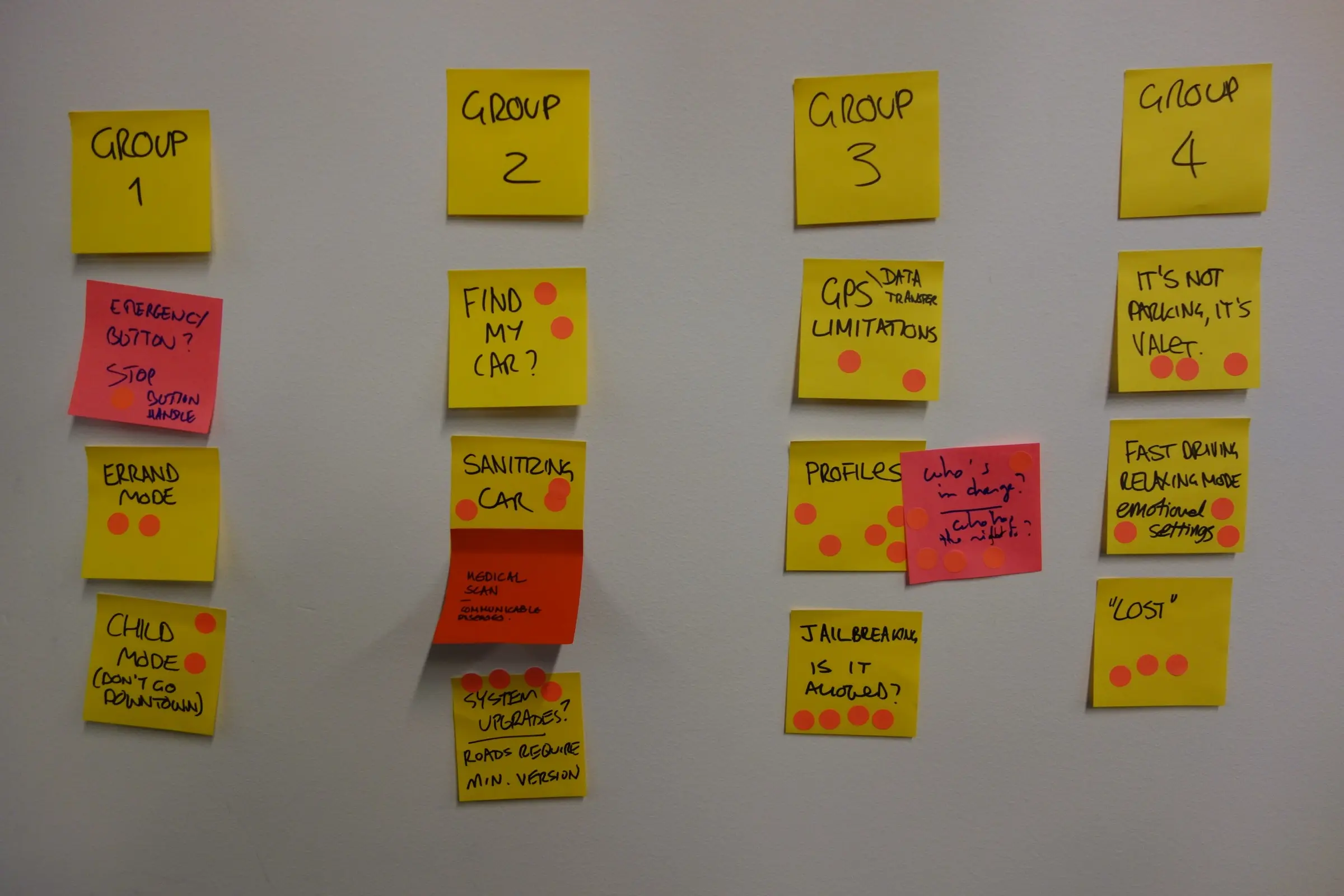

The Design Fiction Workshop

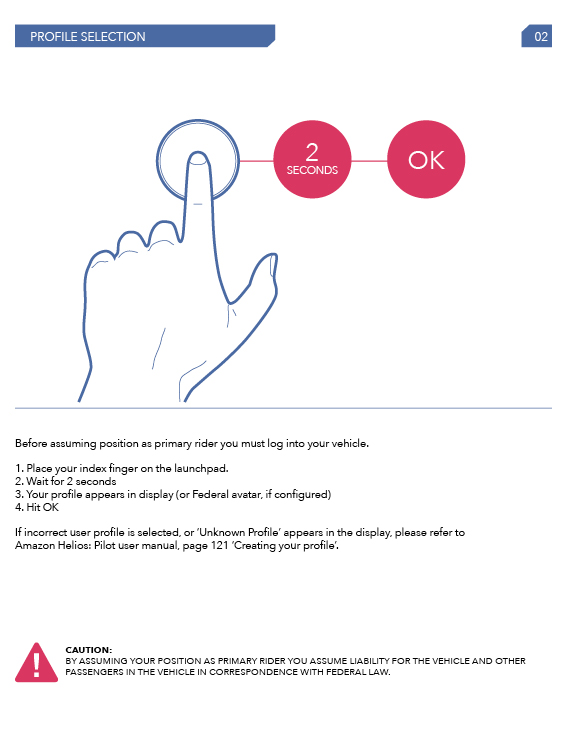

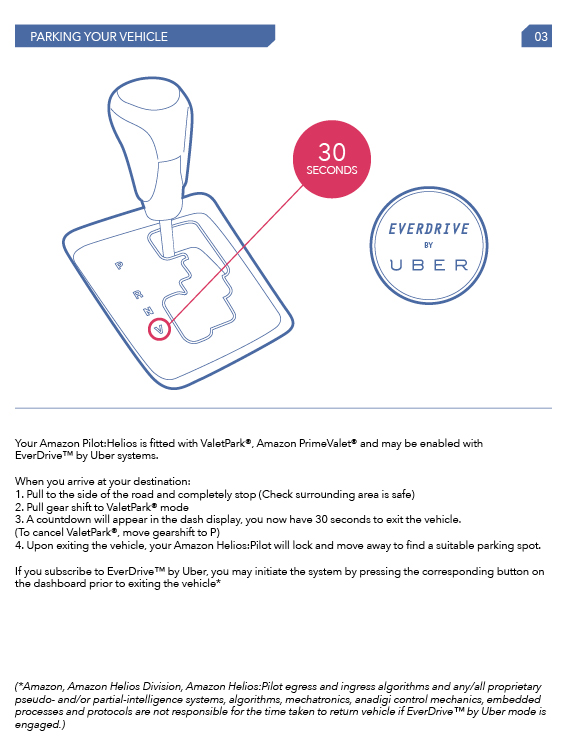

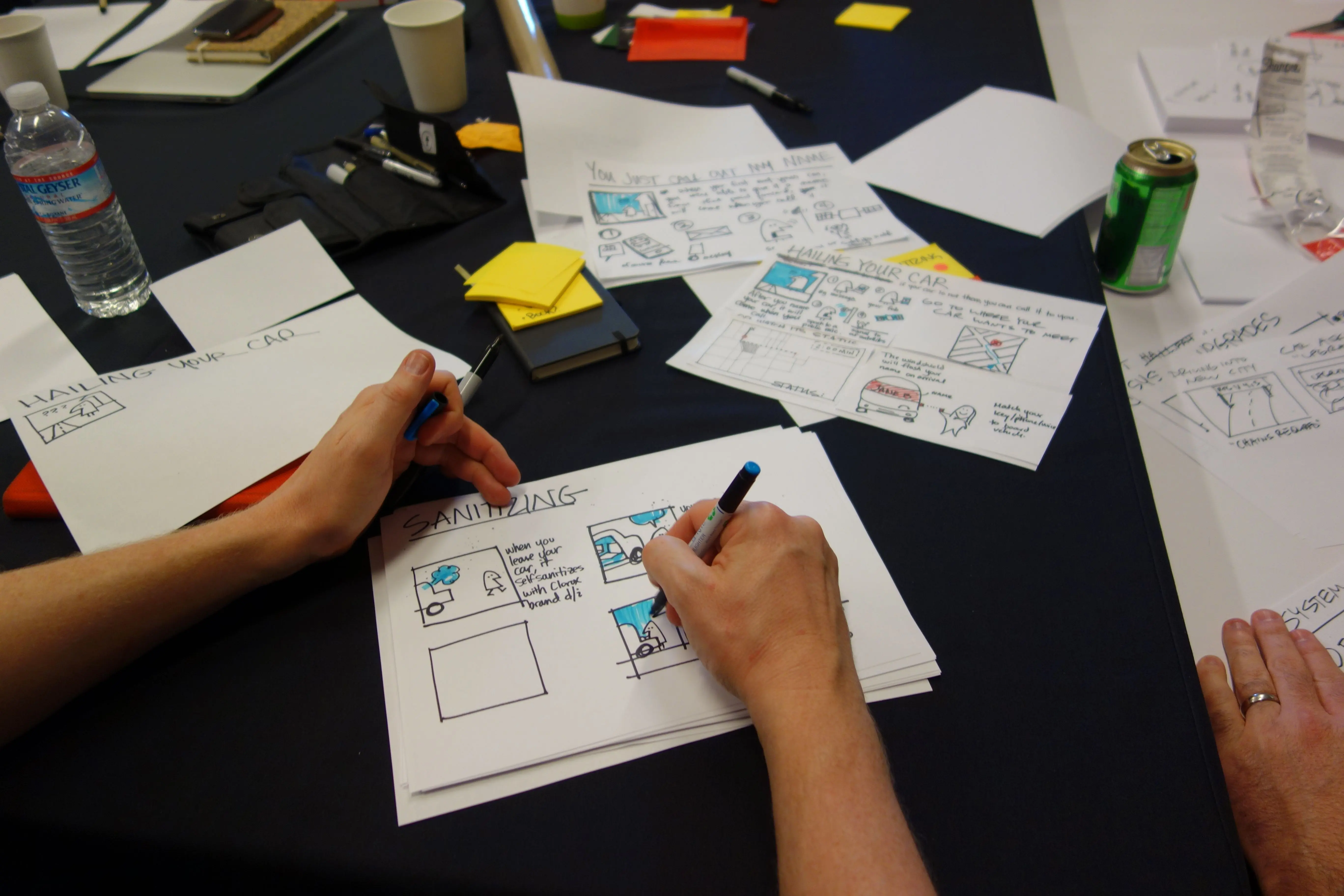

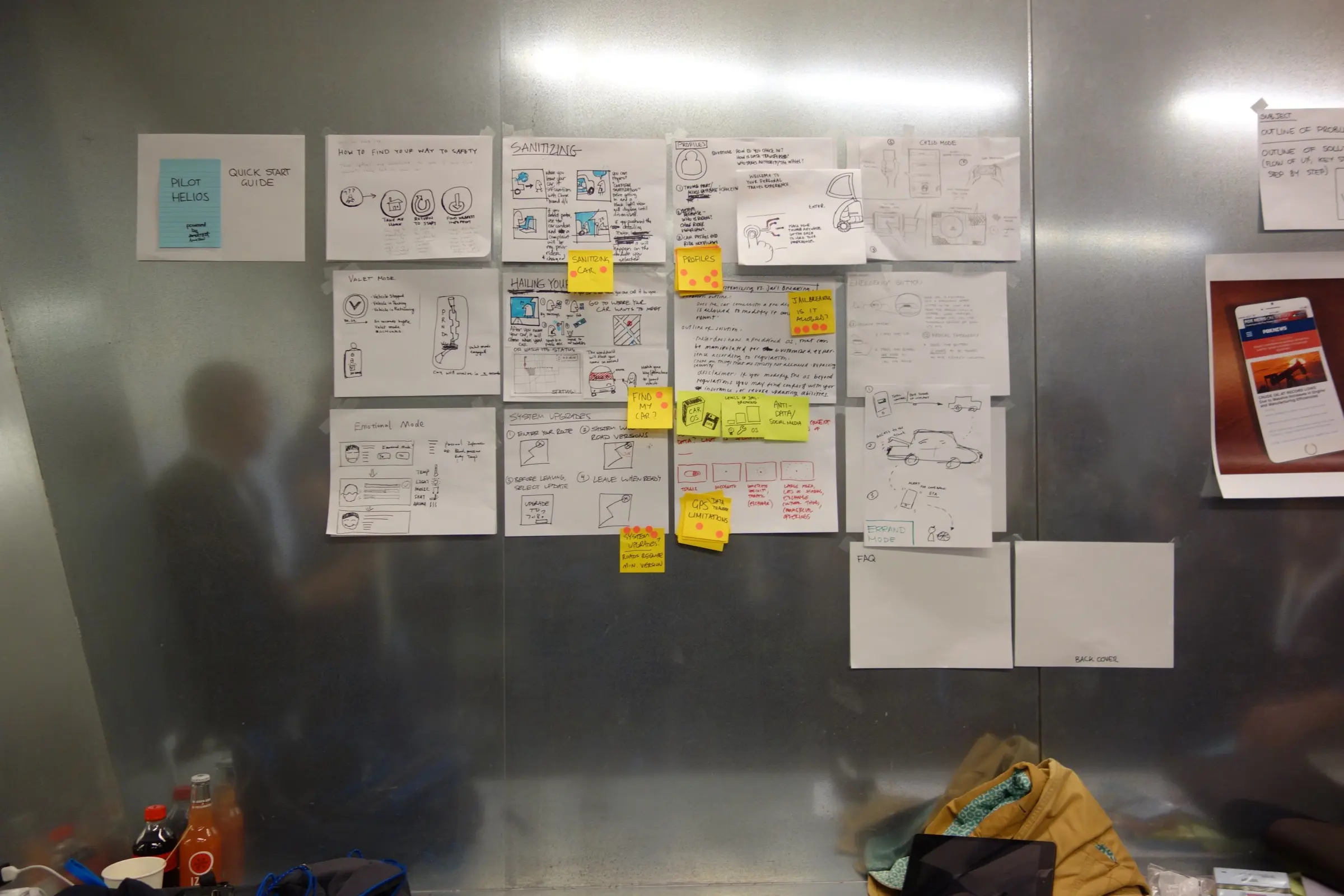

Together we followed a Design Fiction approach to produce a Quick Start Guide for a technology that could substantially change mobility in the future. First, over the course of four hours we identified the key systems and the FAQs that implicate the human aspects of a self-driving car. For each key system, we illustrated the interaction, described the system and the steps for its use. The FAQs represented what we determined might be questions raised by the new self-driving car owner. Using the Quick Start Guide format as a Design Fiction archetype provided a way to focus the workshop discussion in order to identify topics that may not come up when discussing the larger system. It also forced us to create rather than just debate, and represent topics concisely to focus the work and challenge us to describe features succinctly.

This Quick Start Guide Design Fiction archetype is a natural way to focus on the human experiences around complicated systems. The Quick Start Guide implies a larger ecosystem that indeed may be quite complex. It also allows one to raise a topic of concern without resolving it completely — often an approach that’s necessary in order to not be bogged down in details before it’s necessary. For example, mentioning that it costs more to park your car rather than sending it back on the roadway as a taxi is a way to open a conversation about such a possibility and its implications for reclaiming space used by parking garages.

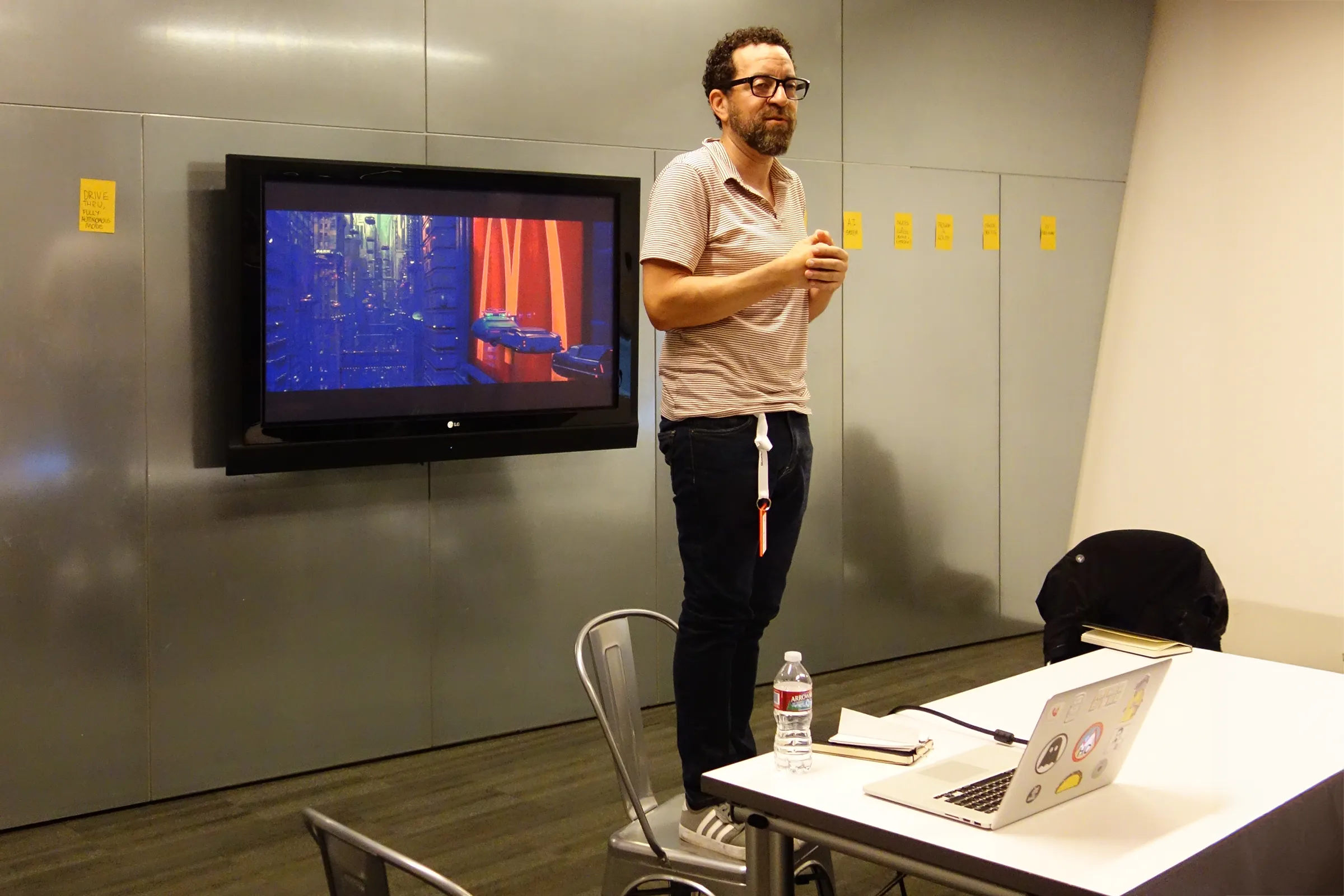

Creating context for the world is an important component for engaging the Imagination and for getting into the mode of being a part of a world where one might be assigned to create this quick-start guide. Providing an entry point for amplifying possible cultural quirks, matters-of-concern, trivial antics, social, cultural, ecological, environmental, political discourse — these are all ways of immersing participants in a world for which they will be constructing one small artifact.

In a short amount of time, we brought to life such experiences in a very tangible, compelling fashion for designers, engineers, gurus, and anyone else involved in the development of a technology. The QSG became a totem through which we can discuss the consequences, raise design considerations and hopefully shape decision making. This approach leads to better thinking around new products, a richer story and good, positive, creative work.

Using Immersion to Create Context

Prior to the workshop, we worked with several California College of the Arts graduate students to create stimulus material to help set a context for participants. The effect of immersion helps provide a context for the work ahead, transport participants from the ‘here and now’ into the ‘near future’ with grounded artifacts and news items.

The Near Future of Self-Driving Cars

Visions of exciting future things rarely look at the normal, ordinary, everyday aspects of what life will be like to turn the thing on, fix a data leak, set a preference, manage subscriber settings, address a bandwidth problem, initiate a warranty request for a chipped screen or increase storage. It’s those everyday experiences — after the gloss of the new purchase has worn off — that tell a rich story about life with a self-driving vehicle. In this project, we made a few category assumptions.

First, the self-driving vehicle is all about the data. When Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Google and/or Apple become part of the vehicle “ecosystem” — either by making cars, having their operating system integral to the car, owning roadways or whatever their strategy teams are dreaming up — they will do it because #data. To them it will be about knowing who is going where, when they’re going there, to get what; it will be about knowing when your tires are wearing down; it will be to give you discounts when send your car to get Pizza Hut for dinner; it will be to have your car go through the Amazon Pantry Pickup Warehouse to do your grocery shopping. The data.

Second, as fundamental as mobility is to humans, owning a network of millions of interoperable vehicles is big business. Apple’s vehicle ecosystem will be always moving, as will Google-Uber’s. It will cost you more to park your self-driving car because it can earn money for them (and maybe you) by putting it into “Taxi” or “Uber” mode when it’s dropped you off at work. This led us to consider what one might need to do if one’s car has strangers in it while you’re at work, or the movies, or asleep. And what will happen to all those parking garages?

Third, roadways will be the new platform play. How will (or will not) roadways that are owned by Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, Google and/or Apple interoperate? Will Google have the best, fastest, least congested roadways in Los Angeles? What are the consequences of switching to semi-partial manual drive mode? What happens when those Fast and Furious guys figure out how to jailbreak their vehicle’s OS and supercode the engine?

Contributors

Rafi Ajl (CCA), Phil Balagtas (GE Global Research), Sankalp Bhatnagar (Carnegie Mellon University), Julian Bleecker (Near Future Laboratory), Maru Carrion-Lopez (CCA), Wendy Cown (Charles Schwab & Co.), Bill DeRouchey (Aviation GE), Blake Engel (Nextbit), Nick Foster (Near Future Laboratory), Cristina Gaitan (CCA), Susan Hosking (GE Global Research), Shani Jayant (Intel), Flemming Jessen (Designit), Zhouxing Lu (Indiana University Bloomington), Chris Noessel (Cooper), Anna Mansour (Intel), Nicolas Nova (Near Future Laboratory), Angelica Rosenzweigcastillo (GE Global Research), Margaret Shear (Margaret Shear | Experience Design), Liam Woods (CCA) and Aijia Yan (Google).

Special thanks to John Sueda, Ben Fullerton and Raphael Grignani.

Use the Contact Form below to discuss how you can engage Near Future Laboratory to help you make sense of your organization's possible futures.